If you are looking for a discussion about early rock and roll, I’m afraid you may be disappointed.

You can’t judge honey by looking at the bee

You can’t judge a daughter by looking at the mother

YOU CAN’T JUDGE A BOOK

BY LOOKING AT THE COVER

written by Willie Dixon

recorded by Bo Diddley, 1962

On the other hand, you may find this of interest if you own any books. Or if you’ve ever just wanted to know how books are made. Or maybe if you work in a library.

What we are talking about here are things that affect a book’s chances of long-term survival, specifically in library collections.

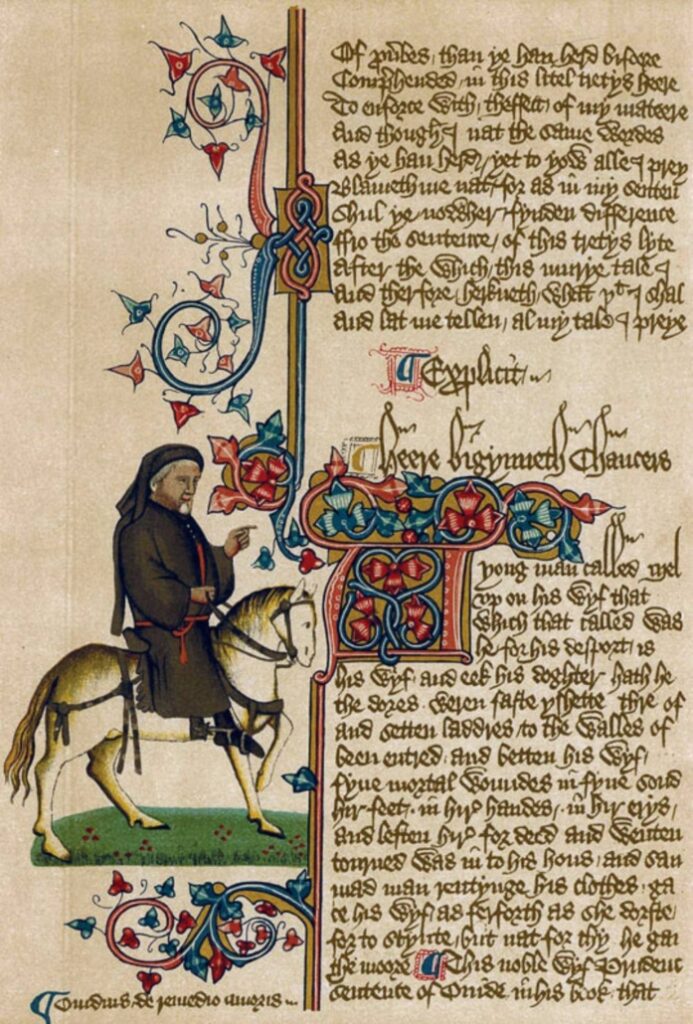

Comes all this new corn from year to year;

And out of old books, in good faith,

Comes all this new science that men hear.

Geoffrey Chaucer, Parlament of Foules

Book conservators know how books are made — and importantly — why and how they fall apart. So I’m going to share some secrets about how you can distinguish between a book that is likely to last and one that may not.

Hint: One with a worn cover could very well be a better choice than one that looks good from the outside.

In truth, the choice is not always clear-cut. But still, better choices can be made — and made more easily — when armed with information about the physical aspects of books and how they are put together.

Book conservators work hard to keep books in good condition so that they will be there when patrons need them.

But do you know what has helped the survival of our collective intellectual record much more than all the efforts of book conservators?

Lots. Of. Copies.

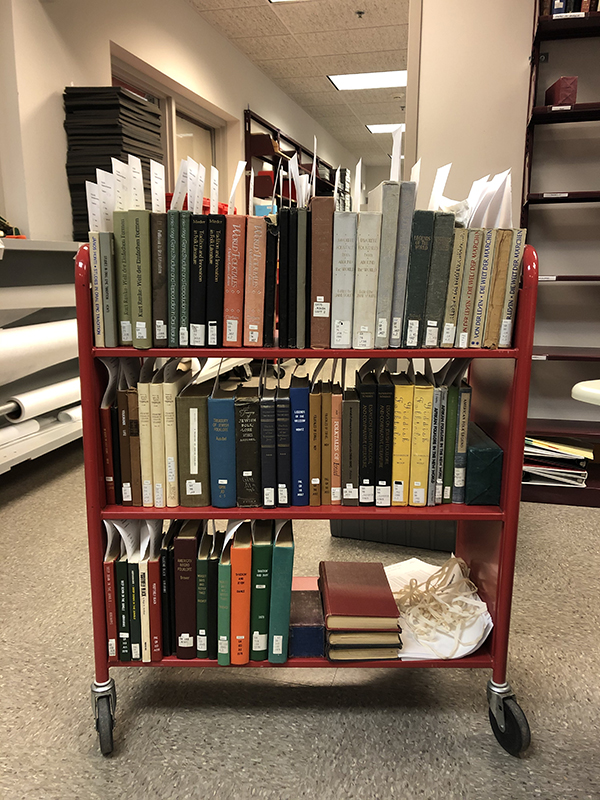

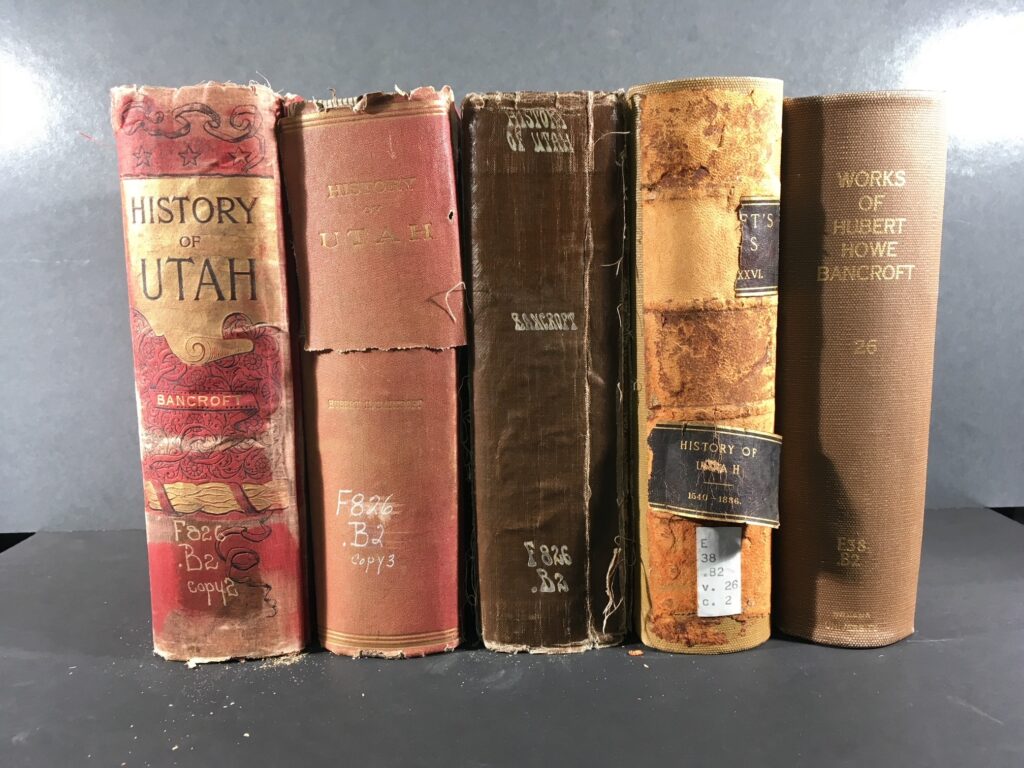

Any book or journal is likely to be found on the shelves of many libraries. Everybody knows that, and that is a good thing. And an individual library very likely has duplicates within its own collection, as you see pictured above.

Redundancy is good in the world of information preservation, whether it is physical books or backups of your computer files. When bad things happen to good books — as they do — there will still be other copies.

So why worry about better or worse copies when we have lots of them?

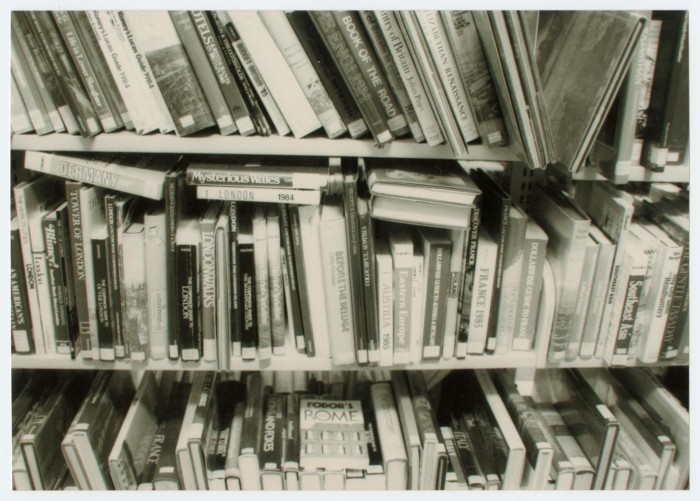

Well, in recent decades the cost of maintaining vast print collections has become a pressing problem for research libraries. The space devoted to books diminishes a library’s capacity for other things, such as study space and meeting rooms for patrons. When libraries run out of space, difficult choices often have to be made.

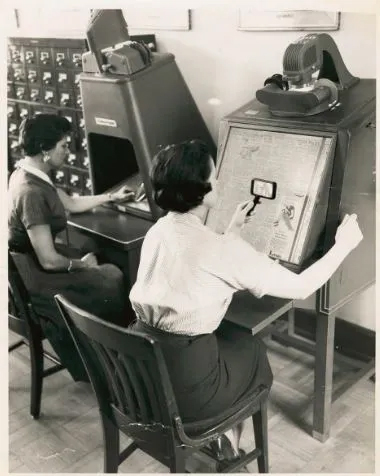

Since the 1950s, when post-war prosperity led to increasing rates of collection growth, libraries have been very resourceful about finding ways to cope with space problems.

Microforms reduced the footprint of voluminous materials such as newspapers.

Compact shelving was added.

Interlibrary lending meant a library no longer had to acquire every book for its users to have access to them.

Was File Sharing Before It Was Cool

When those measures were no longer enough, high-density storage facilities were built to house books efficiently by size on 30-foot-high shelves.

But today many libraries have filled up these facilities too, and financial support for yet more space has been hard to come by.

So what now?

You see where I’m going here.

Shedding some of the copies would seem like a reasonable next step, especially widely held older materials, which are no longer used as much as they once were.

So this is indeed what many libraries are up to these days — withdrawing some copies, either within their own collections or in collaboration with other libraries. Being more selective about gifts. Making commitments to retain their copy of a book in a shared print repository so that others can withdraw theirs.

I’ve suggested that looks can be deceiving to the untrained eye when it comes to judging which copy of a book has better odds of long-term survival. And I promised to share what book conservators know about how books are made, and how and why they fall apart.

So now let’s look under the hood (the covers, that is).

First, though, we have to talk about paper.

Way back when, before the Industrial Revolution, paper didn’t grow on trees.

It was made out of fibers reclaimed from cotton and linen clothing and other rags.

photograph by Eugene Atget

But when the increased demand for paper in the early nineteenth century led to rag shortages, papermakers began switching to wood pulp.

Unfortunately, wood-pulp paper becomes acidic, weak, and brittle over time, unlike older paper made from cotton or linen fibers, which remains strong and flexible for centuries.

By the 1980s, with the problem quite evident in library stacks, preservation folks launched a big campaign to get papermakers to convert their mills to making acid-free paper. Today most new books collected by libraries are printed on alkaline, or so-called permanent, paper.

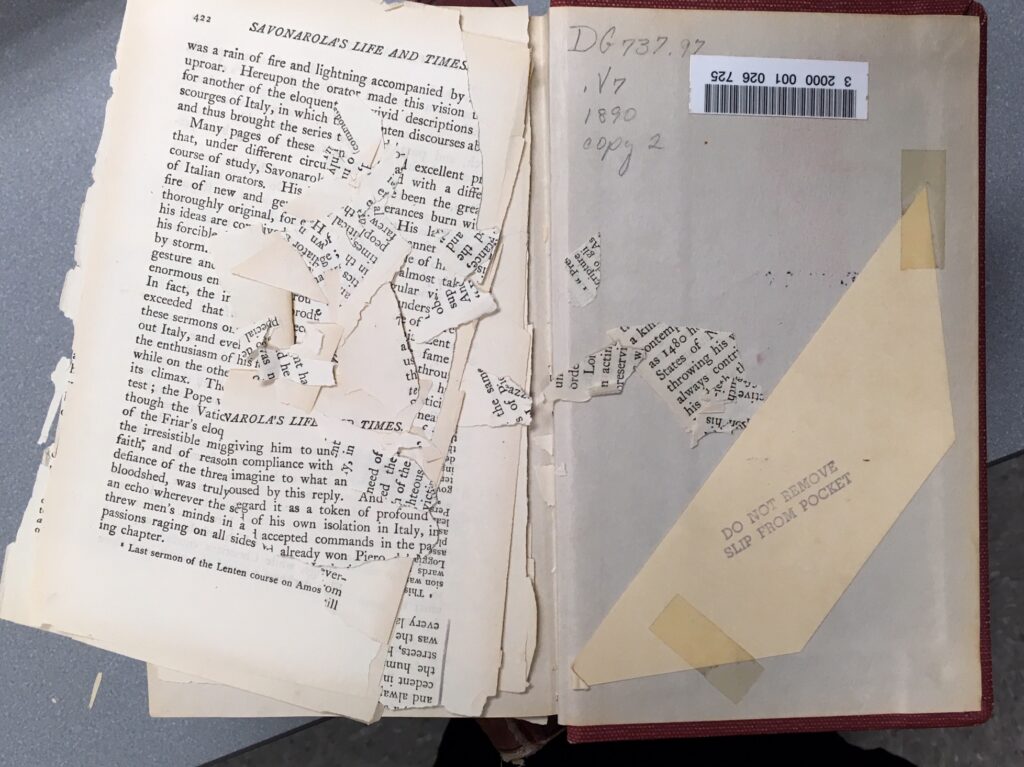

But between the 1840s and the 1980s millions of books were produced on paper destined to weaken and become brittle. And libraries have lots and lots and lots of them.

So the condition of the paper is a big factor for long-term survival.

But now you are thinking that copies of books published at the same time are likely to have the same kind of paper, right?

And you would be correct.

So this doesn’t help a lot by itself when comparing copies. But it is usually a combination of factors that leads to a book’s demise. One is the paper strength, or lack thereof.

So what is the other factor?

The essential thing that makes a book a book is that the pages are joined, or bound, together along one edge. There are numerous ways this can be done, and in library collections the binding method often does vary from one copy to the next.

Why?

- Older books in libraries are likely to have been rebound at some point

- Publishers sometimes issue the same content in different formats – deluxe editions, paperback vs. hardcover

And of course the condition can vary from one copy to the next depending on wear and tear from use and the environmental conditions in which they have been stored.

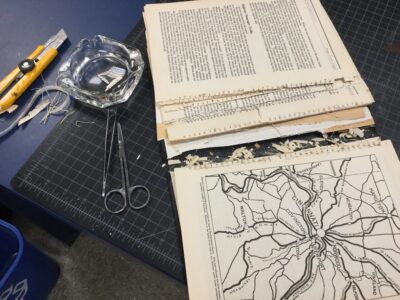

To wit, these five copies of the History of Utah. Each one was bound differently when issued, or rebound by the library over time.

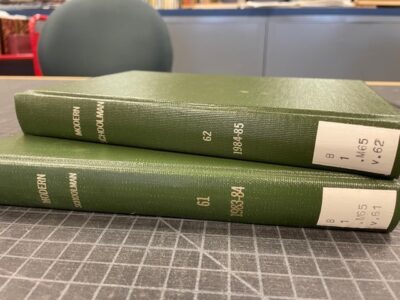

Below are two copies of the same book. The book on top is in its original binding and the one below was commercially rebound.

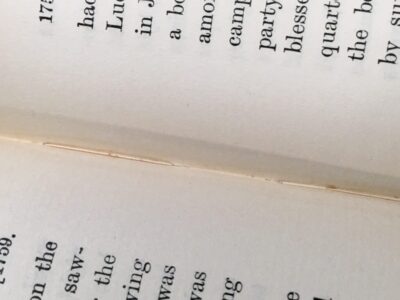

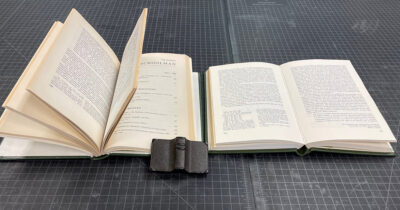

Here they are opened – the original binding is on the left and the rebound one is on the right. Notice anything different?

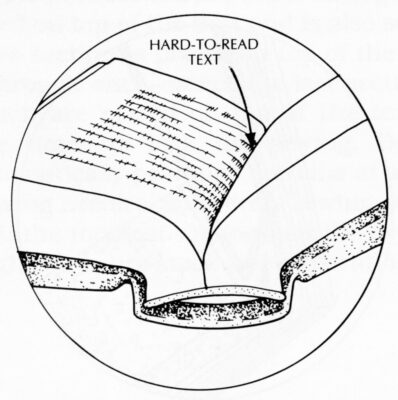

Openability

If you remember only one thing from this blog, remember this concept! Openability.

This is a simple but important thing to look for: Whether a book lies open on the table by itself, or if you have to hold it open to read it, or mash it down on the copier or scanner.

The binding method – the way the pages are joined together — largely dictates openability.

Openability is important, not just because books that don’t open well are inconvenient to use — although they are — but because a restricted opening is a telltale sign of a binding method that makes future repairs difficult or impossible. This is a critical thing in a library whose mission is to serve today’s researchers and those far into the future.

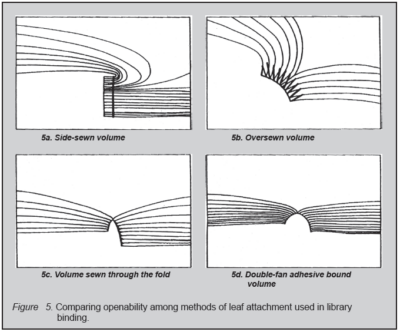

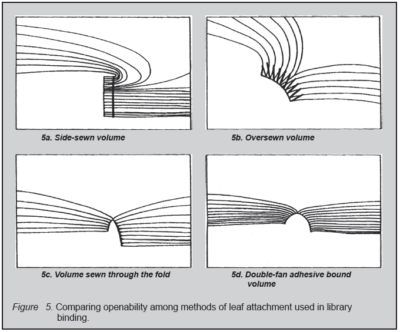

The two at the top do not open easily. That puts a lot of stress on the pages.

The two at the bottom open easily and allow the pages to move freely without stress.

SO.

A book that has both brittle paper and poor openability is likely to end up broken and sad. And difficult to save. But when a book is bound in a flexible manner, there’s hope, and the chances are better that it can be repaired and lead a long life.

So let’s examine the most common ways that books are bound and talk about ways to identify each one.

First let’s look at one that has good openability and works well.

Sewing Through the Fold

Sewing Through the Fold is a traditional method of joining the pages of a book together to form a text block. This method has been in use since as early as the 2nd century AD. So it’s kind of time tested.

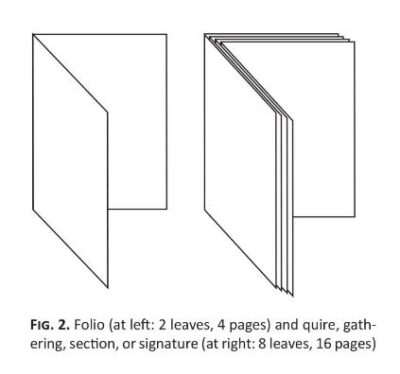

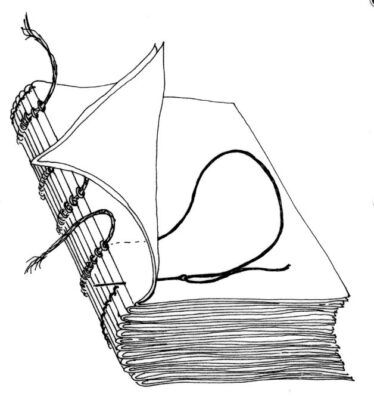

Sheets of paper (folios) are folded together in groups, and then the groups are sewn one to the next with needle and thread.

The needle and thread goes only through the very center of the folds.

Signatures are sewn through the folds and linked one to the next with the sewing thread

Attaching the pages together through the folds makes a book that opens well, is flexible, and allows for future repairs. There is not a lot of stress on the pages, and that is very helpful if and when the paper becomes brittle and weak.

This is still the way that lots of books are made. Sewing through the folds can be found in hardcover and paperback books.

Identifying Books Sewn Through the Fold

You can usually see a scalloped edge at the head and tail of the text block.

Most of the time, you won’t be able to see the spine of the book where the sewing is obvious. But you can look for this scallop pattern at the top or bottom edge of the book. You can see that it is folded groups of pages.

As you page through a book you’ll come to the center of a signature and you may see the stitches – they are long and regular. But sometimes it can be difficult to find a center fold and see the stitches.

And of course, books sewn through the fold open well and do not need to be held open.

So you have these three clues for books sewn through the fold – the openability, the scalloped edge at the head and tail of the book, and the stitches in the center folds.

Oversewing

The oversewing machine was used extensively by commercial library binders to bind library journals, rebind damaged books, and bind paperbacks in hardcovers from its invention in 1920 until the mid-1980s. This means that journals published between 1920 and the mid 1980s are likely to have been oversewn, because journals are generally bound within a year or so of their publication dates. Until the 1980s, most research libraries sent brand-new paperbacks to the commercial bindery for hardcover binding, so most paperbacks that were oversewn fall into the same publication dates. But worn and damaged monographs that were oversewn include many with publication dates prior to 1920.

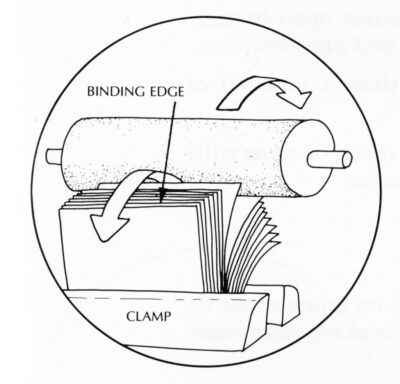

An oversewing machine.

A few pages are put into an industrial machine that has a row of threaded needles. The needles and threads pierce through the page edges many, many times. Then another clump of pages is added, and the machine sews through them and interlocks the stitching with the one before.

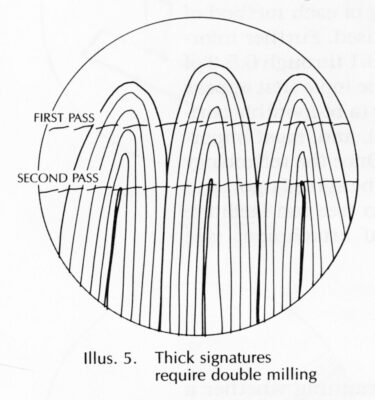

Books and journals are prepared for oversewing by chopping or milling off the inner spine edge so that pages become single sheets of paper.

The dashed lines in the illustration below show where the folds are chopped or ground off.

Below you see how the needles and threads pierce through what remains of the margins.

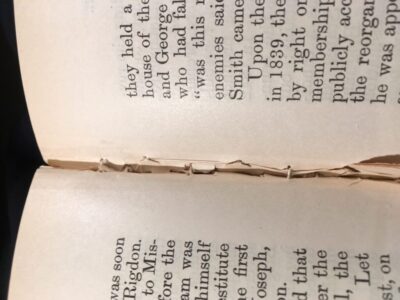

There is a loss of inner margin — first from the trimming and then from the sewing.

This is what oversewing looks like on the spine – a thick mass of threads.

Oversewing is very, very strong — an oversewn book with flexible paper and adequate margins is probably going to last a long time.

But if the paper is brittle, there will be a lot of page breakage, and you may not be able to put Humpty Dumpty together again. One page cracks, creating a knife edge that causes each subsequent page to break.

You’ve seen that oversewing reduces the width of the inner margins, which is part of the reason they are difficult or impossible to repair or rebind again. But if the margins are already narrow, the paper is brittle, and the book is oversewn, the breakage can also result in text loss.

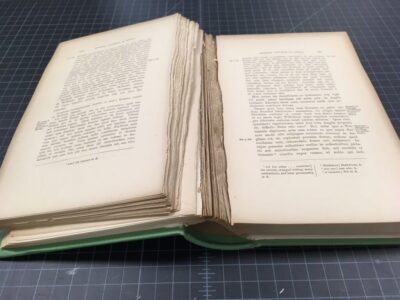

The thin book pictured below took about three hours to take apart, snip by snip. And what you end up with looks like it was torn from a spiral-bound notebook. These pages were not terribly brittle, and the margins were decent, so the result was not that bad.

Practically speaking, though, oversewing is an irreversible binding method.

Identifying Oversewn Books

Besides the restricted opening and the typical buckram cover of a commercial library binding, another way to tell that a book is oversewn is to look for the close, irregular stitches in the inner margin. This is often visible in older books as they start to weaken.

So, the identifying features of oversewing are: poor openability, text may be obscured at the inner margin, plain buckram cover and stamping on spine, and irregular, clumpy stitches sometimes visible at the inner margin.

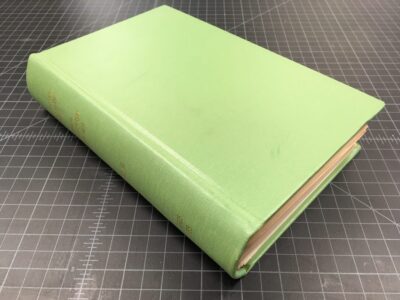

Commercial Library Binding

Now let’s talk about one more binding method, which is done by commercial library binders (and can also be done by in-house book repair operations).

A commercial library binding is recognizable by the plain, sturdy buckram cloth cover material and uniform stamping on the spine. And we’ve discussed that oversewing was done by commercial library binders. But are all books bound by the commercial library bindery the same inside?

The one on the left, v.61, is oversewn. I couldn’t even get it to stay open for the photo – I had to use a weight to keep it from snapping shut.

The one on the right, v. 62? No, good guess, but it’s not sewn through the fold. It is another binding method that has good openability like books sewn through the fold. It’s the method that replaced oversewing in the 1980s. At Indiana University, oversewing stopped after v. 61, 1983-84 and before v. 62, 1984-85.

What happened in the 1970s and 1980s?

Well, a lot of things …

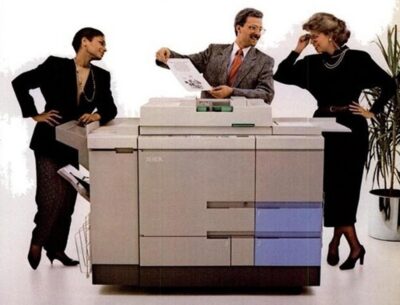

Photocopiers

The problem with oversewing and other restrictive binding methods became quite obvious with the advent of photocopiers available for use by library patrons.

A few other things happened in libraries in the 70s and 80s–

- Growing awareness of the brittle paper problem

- The formation of preservation departments in research libraries

AND

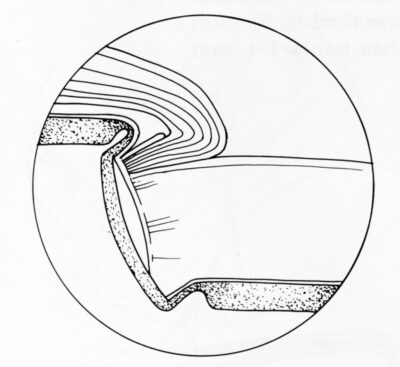

Double-Fan Adhesive Binding

Preservation librarians and commercial library binders worked together to come up with a new binding method that could be used for books and journals that otherwise would have to be bound by oversewing or other machine “side sewing” methods.

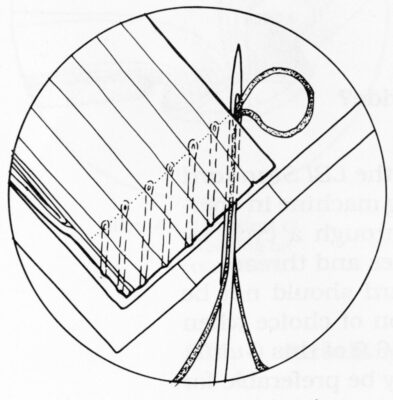

These photos show how the adhesive is applied. The pages are fanned one way, glue is applied with a brush or roller, then fanned the other way and more glue is applied. Doing this gets the adhesive a tiny, tiny bit in between the pages — about 1/32 of an inch.

Double-fan adhesive binding also uses a high-quality adhesive that remains flexible over time vs. a cheap one that dries up.

Identifying Double-Fan Adhesive Binding

A double-fan adhesive binding opens well and stays open easily.

When you view the top or bottom of the text block, there is no scalloped edge, just a thin layer of lining cloth.

So, let’s review —

Binding methods with good openability, which are flexible and repairable —

- Sewn through the fold (5c)

- Double-fan adhesive binding (5d)

Binding methods with restricted openability, which puts stress on pages, and are difficult or impossible to repair —

- Oversewn (5b)

- Side sewn (5a)

Putting all our eggs in one basket

If we are going to put all our eggs in one basket, so to speak, by reducing the number of copies of books held in libraries, let us try to choose books that have the best chances of long-term survival when we can.

I hope I’ve given you some new information that you can use – especially if your work involves making decisions about retention in libraries.

For more information on book structures:

And for more in-depth information, there’s the AIC Book and Paper Group Wiki.

And this paper is an excellent analysis of the many factors involved in withdrawing copies:

Considering Sameness of Monographic Holdings in Shared Print Retention Decisions.

Leave a Reply