For many years, Dino Everett spent his time as a touring punk rock musician, but in the back of his mind were a love of movies and his grandfather’s stories of the silent films he had watched as a child – films that were no longer accessible. After reading Tony Slide’s Nitrate Won’t Wait in the early 1990s, Everett decided to act on his lifelong interest in film and join the archival field in earnest.

Everett’s longtime interest and involvement in punk rock subculture helped inform his work in the audiovisual preservation field. “I look at everything through punk rock eyes and believe that you can do a lot of good with very little, that DIY ethic,” he explains. This DIY ethic is evident in Everett’s current role as the Archivist of the Hugh M. Hefner Moving Image Archive at USC. After working as an Acquisitions Agent for the UCLA Film and Television Archive for seven years, during which time he implemented changes that enabled safer flatbed scanning access to film prints, Everett accepted the position with USC in 2010. “My job at USC is really the perfect environment for someone like me who has many different interests in the field. One day I get to work on physical film or technology preservation and the next I get to research aspects of the collection and the history of the school…the sky is really the limit.”

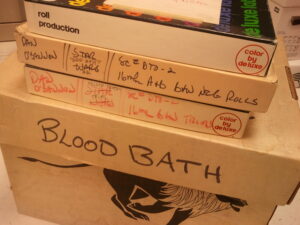

Currently, Everett is working to preserve a number of previously-unseen USC student horror shorts produced in the 1960s by such filmmakers as John Carpenter and Dan O’Bannon. He hopes to compile these films into a feature-length program titled “Shock Value: The Movie – How Dan O’Bannon and some USC Outsiders Helped Influence Modern Horror.” The project, based on Jason Zinoman’s book Shock Value: How a Few Eccentric Outsiders Gave Us Nightmares, Conquered Hollywood, and Invented Modern Horror, is something he hopes to have touring beginning in October 2014. “I figure this could be a great way to raise the awareness of our archive and what we do here, by making these 40 year-old short films into a modern-day product, that I believe all fans of genre films will be interested in.” He adds: “It would be like putting out of a CD of Beatles demos.”

Speaking of outreach, Everett is keen to collaborate with other schools and departments at USC: “Every library and special collection has moving images, and often they are unsure of how to take care of them or transfer them for access, so I try to reach out and let them all know that we are here to help them as well.” Additionally, he extends his outreach efforts to students of both USC’s School of Cinematic Arts and UCLA’s Moving Image Archival Studies program, having set up a workstation that allows him to give students hands-on training with preservation equipment. “I also try to take our equipment out to as many places [as I can] and do live demonstrations for students in various USC cinema and communications classes, such as hand-cranking an old 35mm silent film, or the sound on disc, kodacolor, etc.”

Everett’s outreach initiatives also extend to smaller local entities, such as the Echo Park Film Center and Film Forum, in efforts to make USC’s holdings more freely accessible. “To me, access is the absolute most important facet of the field. If someone is researching something, then I will go out of my way to make sure they get access to the material they need. You’d be surprised how many preserved films are not accessible to researchers.” Citing Penelope Houston’s Keepers of the Frame, in which the author notes that “restoration is seen as a somewhat pointless activity if it does not involve putting the film back into circulation,” Everett argues that how the preservation community treats access is in dire need of change, especially given the rise of digital formats and how bureaucracy often makes access a low priority. “The entire reason archives exist is not simply to protect the material, but to get it back into the hands of the public in some way. If we don’t, then it may as well have deteriorated. If we take a punk rock attitude, then we are not afraid to invoke such change.”

That same punk DIY ethic Everett exhibits in his professional life also extends to his personal interests, which include collecting film equipment. “My personal quirks tend to lead me in the direction of the failed or not-as-popular things in life,” he notes, citing his interest in silent film stars such as the Hall Room Boys, Roland West, Glenn Tyron, and Walter Forde, performers who are far from household names in the vein of Fairbanks or Pickford. His interest in “the outliers,” as he calls them, led to amassing a collection of equipment such as 9.5 mm, 4.75 mm, 22 mm, and 28 mm film formats. “Next year I plan on making, shooting, processing and then exhibiting some 3 mm film since I have the only equipment that exists in the world.” Everett notes the importance of recognizing and sharing the diversity of film formats, especially in a time in which said diversity is becoming more and more obsolete. “I like thinking of the days in the 1960s and 1970s when an amateur cinematographer had close to 10 format options available to them. Now, you are going to be left with one, which to me does not inspire much creativity.”

Utilization of these diverse older technologies is something Everett hopes to see more of in the preservation field. “We are keepers of history and that needs to be exhibited…the content was once everything because the carrier seemed universal, but now that the carrier is being changed I believe it should become part of the preservation.” Another project he is currently working on is a documentary about early cinema technologies; it involves the re-creation of a film from 1910, using a preserved Pathé 35mm Cinématographe as a reference point. “A well-known Hollywood cinematographer is working with me and he is going to shoot the film using this 100 year-old technology…[the documentary will] show the obstacles faced back in the day with the limitations of the camera, but also [will] prove how well-made these things were that you can still use them 100 years later.”

In reflecting on a career that combines his numerous interests, Everett remarks, “My best and worst trait is my passion for both the field and the work. It gets me in trouble sometimes because the punk rocker in me makes me stand up and shout my opinion, and let’s face it, opinions are not always facts. If I am ever able to make a tiny mark on this field I would hope it would be in a fashion where deep down, people would know that I do everything I do simply because of a never-ending passion for this field.”

Never-ending passion: punk DIY ethos at its finest.

~Kaitlin Conner

1 Comment

Dino Everett — I am working to preserve a collection of 1930s film shot in Hawaii and Korea, and 1940s film from post-war Europe. It’s tough finding connections although I am your neighbor in Pasadena, CA. Any advice or recommendations is welcome. ~DML