Nathan Salsburg is the Curator of the Alan Lomax Archive at the Association for Cultural Equity (ACE). The ACE was founded “to explore and preserve the world’s expressive traditions with humanistic commitment and scientific engagement.” As home to the Alan Lomax Archive, the ACE preserves and promotes the life’s work of the ethnomusicologist, including thousands of sound and moving image recordings, photographs, and field notes.

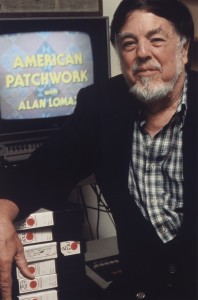

Nathan was kind enough to answer some questions about his experiences in audiovisual archiving and curation in anticipation of his presentation in Bloomington May 25th, 2014. An Evening of Music and Film with Nathan Salsburg and the Alan Lomax Archive will showcase raw footage from the recordings that eventually made up Lomax’s PBS series “American Patchwork”. The event will also feature a solo guitar set by Salsburg and the screening of some rare 16mm music-themed footage presented by the IU Libraries Film Archive.

IU Libraries Film Archive: How’d you get into this line of work? What was your path to the very cool title of “Curator of the Alan Lomax Archive at the Association for Cultural Equity”?

Nathan Salsburg: I came to it as a fan, which I still am. I was raised on my parents’ Dave Van Ronk, Mississippi John Hurt, and Dylan records, and after I graduated college and moved to NYC in the summer of 2000, I wrote the Woody Guthrie Archive (then based in Midtown), who took me on for a couple afternoons of volunteerism. They told me the Lomax Archive was hiring and I applied. Started that fall: making coffee, doing post-office runs, writing accession numbers on DATs, if that gives you a sense of the period. Had considered some kind of grad program in folklore or ethnomusicology, but the reality of paid work with one of the largest and most storied private collections of field recordings eclipsed that idea, and has done since.

IULFA: In this very professionalized field, you are unique in terms of your credentials – you don’t boast an MLS or specialized degree in archives/preservation. How has this hindered/helped your work?

NS: Ha, that’s a nice way to say that I have no credentials whatsoever! Right, my primary interest was never in collections management or preservation or any of that — I wanted to put out records. Not long before I arrived, the Archive, under the direction of Alan’s daughter Anna Lomax Wood, had succeeded in digitizing all of its audio, photo, and video and film collections; this dovetailed with the launch of Rounder Records’ 100-CD “Alan Lomax Collection” and an emphasis on both licensing and digital cataloging, ultimately with the goal of complete online access and direct digital dissemination to other institutions. By 2004 we had largely become a digital archive, with all of Lomax’s original media being accessioned by the Library of Congress’ American Folklife Center as part of their Lomax Collection — which united Alan’s post-1944 recordings with the early ones he made with his father under the Library’s auspices (1933–1944) — and by then most of my work was taken up doing editorial on what became ACE’s Online Archive. Then in 2008 I started putting together albums of Lomax’s recordings for various outlets. So the issue of my particular credentialessness was never put to the test, as I’m lucky to be involved at a time in the collection’s life when I can be most useful as an editor and a curator.

IULFA: How has the Lomax Archive changed during your tenure? What are some challenges you have today that you didn’t have when you started?

NS: The Archive was really ahead of the digitization curve — Anna went after and got support from big grantors like NARAS and Save America’s Treasures (since done in by the Federal Government). For several years we were one of the biggest sound archives to have for all intents and purposes all of its collection in digital formats. That, obviously, gave us the leg up we needed for launching the online research center, and also gave me the chance to move back home to Kentucky with all of the Lomax Archive in a few hard drives. So that was certainly the biggest change — analog to digital — and it felt good to give presentations at conferences on our digital initiatives and get a room packed with curators and archivists and librarians who were attempting the same thing with their collections and looking to us for advice.

The irony, though, is that we were too early to build the site with social media in mind, and what seemed so cutting-edge just a few years ago hasn’t fared so well in translation through Facebook, Twitter, and all the rest, and it desperately needs an overhaul. So now the biggest challenge is redesigning the system with an eye to long-term flexibility, durability, relevance, and ease of access online.

IULFA: Your work with patrons must be very exciting and diverse. What kinds of people contact you about your collections?

NS: We’re an interesting case, I think: we get plenty of queries from users of our online archive, but for most in-depth research folks go to the reading room at the American Folklife Center, where most of the original Lomax media — and most associated documentation — is held. So although we’re a digital archive, it’s largely the audio, photo, and moving image that’s accessible online; we didn’t attempt to create an attendant space on our site for Lomax’s papers: even crucial documentation like field logs (although images of most of his tape boxes are available through the site).

We’re lucky to have that partnership in play with the AFC. They’ll handle most serious research requests, but when they get contacted with licensing queries, they’ll pass them onto us. (This is part of saying how lucky we are to have the LOC in charge of the physical preservation of the original media. We’d be in tough shape if we had to shoulder that burden ourselves. And in fact they’re nearly finished with the digitization of the nearly 150,000 papers in the Lomax Collection there.)

But we do get a lot and I mean a lot of usage requests: occasionally for licensing for films and tv, but mostly for University Press books, academic journals, theses, etc. And then so many requests for songs for remixes. I won’t attempt to say what percentage of these do anything beneficial for the original performance, but we do grant nearly every respectful use and try not to let our own tastes get in the way of spreading awareness of the collection.

The best contacts we get, though, are from families of the artists that Lomax recorded. These have increased exponentially over the past few years and that’s thanks to YouTube; we hear from a lot of nephews, grandchildren, cousins, etc., who come across clips of their relative(s) singing or playing or dancing. One of my favorite comments we ever received came from the granddaughter of a leader of a lining-hymn at an Old Regular Baptist Church near Mayking, Ky.

This is my papaw John Wright lining the song!!!!!! I have been to many of his services and there is nothin in the whole wide world like it!!!! It does my heart such good to see and hear him sing again and he_ looks so wonderful to me!!!!! Thank You GOD for being able to see him again till i join him!!!!!

IULFA: Tell us your thoughts about access and outreach, and more specifically, the hugely popular YouTube channel you curate.

NS: YouTube has been such a massive boon to us: in terms of publicizing the collection; making contact with the families of artists; and just getting into folks’ eyes and ears. We’ve got over 15,000 subscribers and nearly six million views, which is just such an exponentially bigger audience than Lomax’s work has ever had previously. He would have flipped had he been able to see what YouTube makes possible, not just in terms of the reach of his own collections, but more generally in terms of the potential for cultural self-representation. Lomax insisted as early as the early ‘60s that there were too many media receivers and too few transmitters, and the arc of the second half of his career was largely dedicated to leveling the playing field; the notion of what he called “cultural equity.” YouTube is the most democratic means yet of site-specific players, singers, dancers, etc., doing their own, if you’ll pardon the phrase, “self-collection,” and self-presentation, and self-representation.

IULFA: How about repatriation and the archive?

NS: Being a digital archive lets us do all kinds of things online, but it also makes our repatriation efforts possible. We’ve donated hundreds and hundreds of hours of audio and moving image media, plus many hundreds of still images, to archives, libraries, and community centers all over the world, for the sake of returning Lomax’s collections to the places they come from. The most recent one of these repatriation events was held at the Senatobia Public Library in the Mississippi Hill Country last October, following a similar event and donation to the library in Como down the road a year earlier. (You can read more about the events here, and a more impressionistic piece I wrote here.) Seeing the response from the community, and specifically from all the family of artists that came to the ceremony, was my proudest moment with the Archive.

IULFA: Finally, can you share a couple of “gems” from Lomax’s recordings with us?

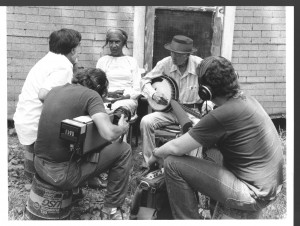

NS: It’s tough with Lomax’s recordings – there are so many of them from so many places, across so many years, but of course I have my favorites: ones that I’ve returned to year after year and that never lose any of their awesomeness, which I mean in the traditional sense (and the vernacular one). In my top five of moving-image favorites is this clip from a 1978 picnic on the Bartlett plantation outside of Como, Mississippi, led by Napoleon (or Napolian) Strickland and his band. Napoleon was a phenomenal multi-instrumentalist – played guitar, diddley-bow, harmonica, and fife – and he shows off the latter two in this segment. The performance is so good, but I also really appreciate how he hams it up for the camera, and subtly directs his band into formation for it, which belies the notion that this is “ethnographic” filmmaking in the traditional sense.

And here’s an audio-only bonus. I’ve worked for the Lomax Archive for 13 1/2 years, and it took me 13 1/2 years to hear this song, which I’ve become utterly obsessed with. Just yesterday (May 15) I stumbled across it in the digital equivalent of the bottom of a file cabinet: Lomax’s 1967 recording session from St. Eustatius, which is this postage-stamp of an island in the Dutch Antilles, south of Anguilla. (I had to look it up.) He was there on vacation with his partner at the time, Joan Halifax, and he obviously was doing some one-off recording with folks he met. This tremendous singer-guitarist, identified only as Alice, sang two English ballads – one of them among the best versions I’ve ever heard of the hoary old “Barbara Allen,” which I’d listened to before, and then this bizarre and hilarious and wonderful ballad called “Jerusalem Cuckoo,” that I’d completely overlooked. I’d love to know where she got these; especially the latter, which has all these Cockney elements, even in the title: “Jerusalem” is rhyming slang for “donkey,” in some impenetrable associative logic. Make sure you listen through to the very end. Everything about it is sublime.

Leave a Reply