Today his works are commonly listed among the best novels of the twentieth century but when Theodore Dreiser entered Indiana University in the fall of 1889, the campus was then home to only 324 students and 28 members of the faculty and staff (this included a Registrar, 3 librarians and 2 janitors). The Annual Catalogue for that year described the campus as “twenty acres of elevated ground, covered with a heavy growth of maple and beech timber. The commanding position of the land, and the beauty of the natural forest render this one of the most attractive college sites in the country.” Wylie and Owen Halls, two framed buildings that housed some of the literary departments, the chapel and an observatory were the only structures on campus. The new Library (Maxwell Hall) was almost complete.

Born in Terre Haute, Indiana on August 27, 1871, Dreiser attended high school in Warsaw, Indiana. Reportedly, his teacher Miss Mildred Fielding sensed his potential and paid for his freshman year expenses to attend IU. In his memoir A Hoosier Holiday (1916), he remembered, “As Miss Fielding, my sponsor and mentor, had predicted, I learned more concerning the seeming import of education, the branches of knowledge and the avenues and vocations open to men and women in the intellectual world than I ever dreamed existed – and just from hearing the students argue, apotheosize, anathematize, or apostrophize one course or one professor or another. Here I met my first true radicals…”

As an IU student, Dreiser lived in a small rooming house in town (apparently rooming with “a popular, good-natured football player”) and took meals at the local boarding clubs.

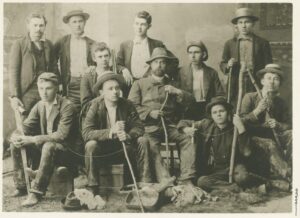

(Back Row, L to R) Walker (this is probably Orie Walker); Samuel M. Knoop; William Alonzo Marlow, Theodore Dreiser (seated), and Francis Elmer Kinsey)

It is evident from his later personal memoir Dawn: A History of Myself (1931) that he was charmed with Bloomington and his surroundings. He reportedly spent much of his spare time exploring the local countryside and in particular the cave system to the south (he even dramatically describes being lost in one of the limestone caverns near town). Of the University he said, “There were, in addition, six or seven other buildings, of brick or wood scattered rather casually over a large and physically varied campus, which to me as I first saw it…seemed very beautiful. A wide brick walk led from the principal street of the town up the hill, at the crest of which and to the sides as one approached stood these several buildings….And to the east, northeast and southwest, were hills and seemingly heavy growths of trees leading interminably hence.”

His courses included elementary Latin, Anglo-Saxon English, geometry and algebra, Philology, study of words, and Virgil’s Aneid. He later reminisced,

“if ever, physically, at least, a year proved an oasis in a life, this one did. For much to my astonishment, the lessons, outside of Latin, were not so very difficult, though as for algebra and geometry, I could not quite see the import of these, to me if to life. They seemed, I having no turn for mathematics or the technique of the sciences to which they so aptly apply, such a useless waste of calculation. Yet history, English literature and the study of words fascinated me, since thusward was the bent of my temperament, but far and above these again in import to me was the life og the town, the character of its people, the professors and the students, and the mechanism, politics, and social interets of the University body proper.”

Dreiser, however, was not meant for formal education and only continued his studies for the one year before returning to Chicago to work for the Chicago Globe. In addition to writing several other works of fiction and nonfiction, he later worked in other positions in St. Louis, for McClure’s, Harper’s, Cosmopolitan, and as editor-in-chief of Butterick Publications. While Dreiser was often criticized for his poor grammar and sentence structure and lack of formal education, today he is recognized as an outstanding American example of naturalism. With the release of his second novel Jennie Gerhardt in 1911, the Indiana Student reported that “critics said that it was not a gem but in reality a chunk cut out of the life of today, and the author a man who cuts it with no pink manicured hands. It is gratifying to those who believe that the teaching of a university should powerfully model public opinion to find men who have gone out from Indiana University analyzing life keenly with virile earnestness and serious purpose….Like many other Indiana authors, Theodore Dreiser impresses those who know his work, with his absolute sincerity; he writes of real people and compels you to see them as he knows them.”

Leave a Reply