100 years ago Emmeline Pankhurst (1858-1928), the British political activist and leader of the suffragist movement, spoke to a packed crowd at Indiana University Bloomington. Women in Indiana women still did not have the write to vote. Raised by politically active parents, in 1879 Emmeline Goulden married Richard Pankhurst, a barrister 2 years her senior known for supporting the women’s right to vote. A staunch advocate of suffrage for both married and unmarried women, Pankhurst’s work became known for physical confrontations, window smashing and staged hunger strikes and is today recognized as a crucial component in the fight for women’s suffrage in Britain.

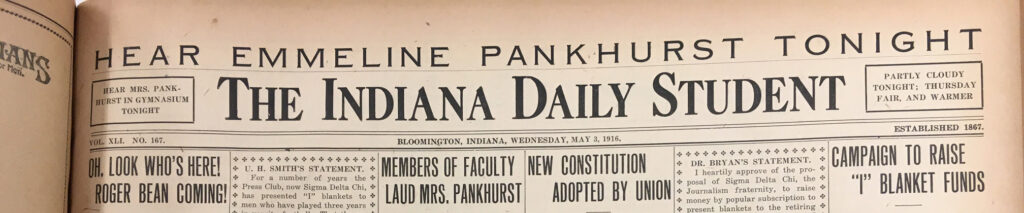

In the lead up to her visit to campus, the Indiana Daily Student reported on April 29, 1916 that

“Mrs. Pankhurst can boast no masculine element in her make-up; she is all woman, in spite of her strenuous activities several years ago. Emmeline Goulden, as she was in her maiden days, was remarkable for the girlish prettiness that time and hunger strikes have not effaced. After the death of her husband, it became necessary for Mrs. Pankhurst to do something to earn a livelihood for herself and children, so she became a member of the School Board and the Board of Guardians in Manchester. Her experience on the later board taught her much of the pressing needs of the poor, and the bitter hardships of the women’s lives especially. Although always active in many reform movements, she found her efforts so much thwarted and limited by her sex, that she finally resigned all other work to devote her life to the winning of votes for women. She organized and managed the great suffrage association of England, the Woman’s Social and Political Union, known as the W.S.P.U.”

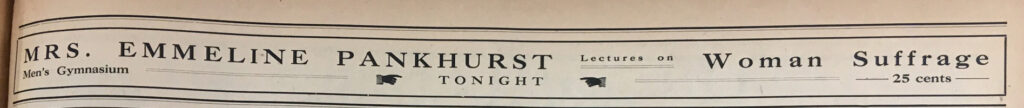

Sponsored by the Women’s League of the University and the Bloomington Woman’s Franchise League, Pankhurst’s lecture was much anticipated, with the student newspaper noting that “This is to be the only lecture by Mrs. Pankhurst in the State and because of the fact that she is so well known, due to her activities in advocating women suffrage, it is likely that there will be a large crowd to hear her speak. The admission will be twenty-five cents. Tickets are now on sale at the University and City Book stores.” Others in the university community likewise expressed enthusiasum for her visit. Professor James A. Woodburn of the History Department, when interviewed concerning the lecture, said

“I have long desired to hear Mrs. Pankhurst. She is one of the most prominent women of the world, and one of the most capable and influential. I heard two of her associates and co-workers in Hyde Park several years ago, and though they were not so effective in speech and leadership as Mrs. Pankhurst is, yet they held more than a thousand standing men in close attention for two full hours. It was a heckling rather than a friendly audience, but the women were so forceful and eloquent, of such quick wit and repartee that they were more than masters of the situation. They carried a resolution overwhelmingly from that crowd in favor of Mrs. Pankhurst, who was then a political prisoner. These English suffragettes are women of education, gentility and refinement. Many of them are of high social standing and most agreeable manners, though some of them may be convinced that to break an Englishman’s head is about the only way to get a new idea into his cranium…whether we agree or not with what they did we must recognize the courage, devotion, and self-sacrifice of their fight.”

Reportedly only in Bloomington for a total of eight hours (she spoke in Nashville and Chattanooga, Tennessee the day before and Columbus, Ohio and Chicago, Illinois immediately following), Mrs. Pankhurst and her secretary Miss Joan Wickham were entertained by IU Professor of Political Science Amos Hershey during their visit.

Introduced to a packed crowd in the Men’s Gymnasium by IU English Professor William E. Jenkins, Pankhurst’s remarks, according to the May 4th issue of the Indiana Daily Student, included a summary of the political conditions in England. She noted that “We did not hunt notoriety. Mere notoriety hunters would have been snuffed out at a very early state of our career. Women do not invite the experiences which we have had unless they feel very keenly their abuses. The difference between a militant and an ordinary suffragette is that we realized a little sooner and a little more keenly the work that women must carry on. There is no excuse for violence until ordinary means are exhausted.”

In 1918 the Representation of the People Act in England granted votes to all men over the age of 21 and women over the age of 30. In 1928 the vote was extended to all women over 21 years of age. Nationally, women in the United States gained the right to vote in 1920 with the 19th amendment.

Leave a Reply