With the 2016 elections close—and the possibility of the election of the first woman U.S. president in history—it’s important to remember how far women have come across the frontier of American politics. As you undoubtedly know, women did not obtain the right to vote in this country until 1920 when the states ratified the 19th amendment to the Constitution. It took almost 100 years after that for a woman to be seriously considered for the highest level of office. But years earlier, in the very wake of women’s suffrage, Nellie Tayloe Ross would become the first woman governor of any state.

Ross became the governor of Wyoming in 1925, easily earning the office after the death of her husband a year earlier. According to many prominent politicians of the time, she was the “woman who made good;” Republicans and Democrats alike agreed, for the most part, that she had done her duty well during her two years in office. With how little effort it took her to get the vote and earn office in the first place, many believed it should have been smooth sailing when the time came for reelection in 1926. A number of women stood behind her and worked the campaign in order to keep her on the Democratic ticket. But the effort proved more difficult than anticipated; enter Cecilia Hennel Hendricks, former IU teacher and alumna, who would see firsthand the obstacles in fundraising for a female candidate.

Cecilia Hennel Hendricks

Hendricks, formerly Hennel, was born in Evansville, Indiana in 1883. She attended IU, performing as an exceptional student and leader both in and out of the classroom, and was even elected as the editor-in-chief of the campus yearbook, The Arbutus, in 1907. By 1908, she had earned both her Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees. For the years to follow, she held positions on the Indiana University faculty as an instructor in the English department and an assistant editor of publications. So how did an accomplished woman living in Indiana with a career underway end up working the campaign for the governor of Wyoming? The same way anyone would: by marrying a bee farmer.

A marriage to John Hendricks of Honeyhill Farm took her all the way to Wyoming for an interlude in her IU career, and after a few years she would find herself swept up in the efforts for women in politics.

The Election of 1926

The Cecilia Hennel Hendricks family papers contains a file with a good chunk of the correspondence between Hendricks and others about Wyoming’s 1926 gubernatorial race. Through these papers, it’s fairly easy to discern her role in the campaign and how she managed to become a part of this political movement. It should be mentioned that Hendricks was not only working for Ross’s reelection at the time, but was also herself running for State Superintendent of Public Instruction under the same ticket– although, it almost seems as though she became more concerned with Ross’s election than her own. She wrote letters to major political and activist figures (mostly women) to either solicit money, ask for lists of other people whom she could solicit for money, or to ask for advice on Ross’s campaign, all the while using the discourse of women’s rights to make her plea. To Mrs. Ruth McCormick, a U.S. representative from Illinois and activist for women’s suffrage, she wrote:

“…For the first time, a woman is a candidate for governor on a purely business proposition, simply on the record of her efficiency. Heretofore the element of sympathy has entered into every campaign where a woman has asked for high office. If Governor Ross were a man, there would be no question in the world of her re-election. She has demonstrated that a capable woman is just as successful as any man. She has shown that there is no sex in brains and ability. It is unnecessary to say that the whole future of women in politics hinges on their being accepted when, and only when, they prove efficient and capable for the job in question.“

From this, Hendricks went on to ask for a donation to the campaign funds.

Not all of her attempts were fruitful. In fact, a majority of the responses Hendricks saved were polite, yet firm rejections to contribute to the campaign. Mary Roberts Rinehart, an American mystery novelist, wrote that she was “not a citizen of the state” and that she “really think[s] it would be an impertinence on [her] part to suggest anyone to them as the party of their choice, or to contribute to the campaign, or to align [her]self on either side of the politics of [Wyoming].” Still, Hendricks remained adamant, writing to a number of other possible donors, including the editor of Good Housekeeping in New York (hoping they would publish an article she wrote about Ross) and Emily Newell Blair, a writer and one of the founders of the League of Women Voters. Blair stated that, although she could not donate, she had convinced others to donate to the cause. Aside from solicitation, Hendricks remained alongside Ross for the majority of the campaign, attending many of her rallies and reporting on the success of her speeches. Her file includes a hefty stack of newspaper clippings that mention Ross’s highs and lows during election and as governor of Wyoming.

The Aftermath of Loss

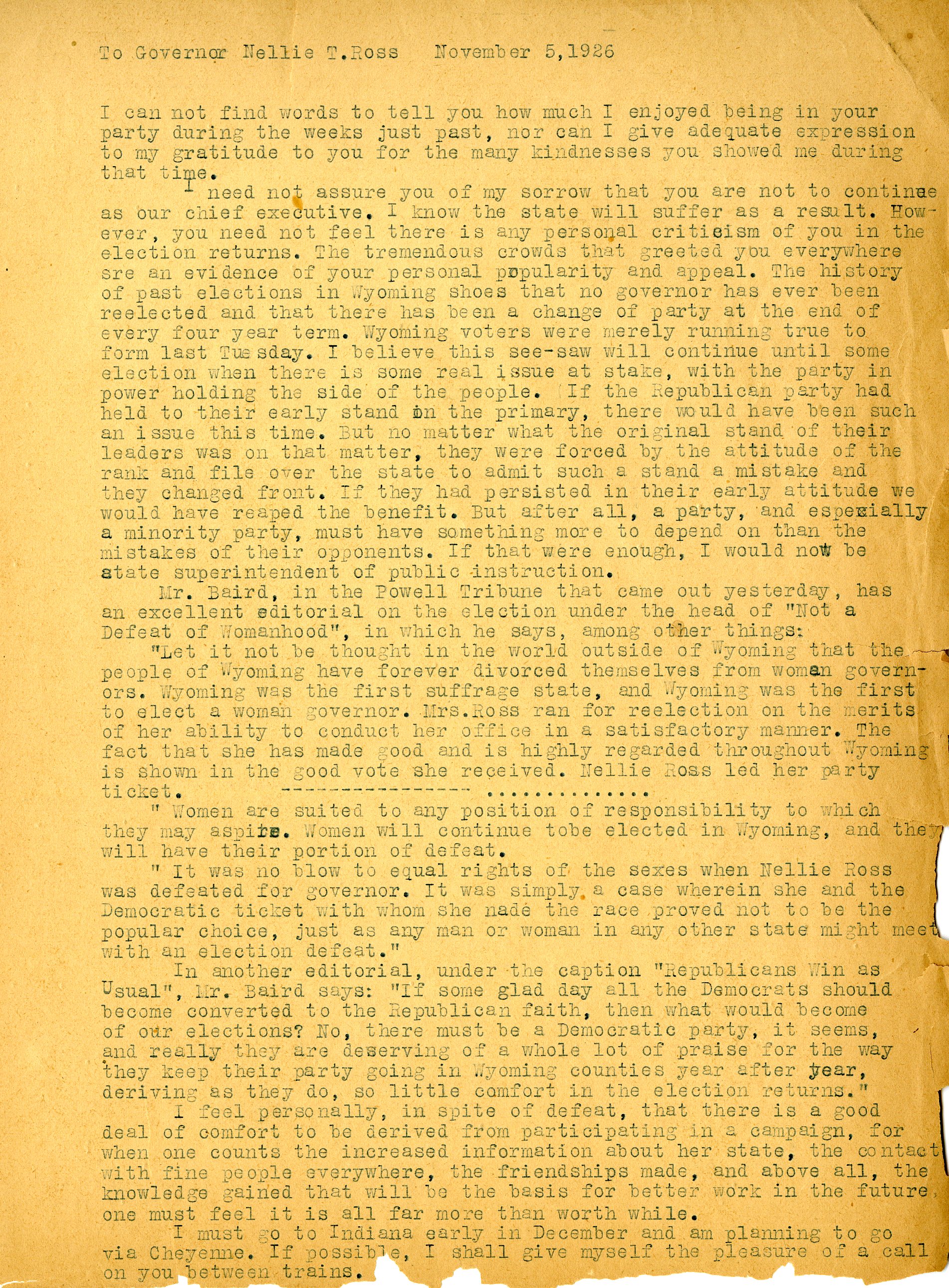

Nellie Tayloe Ross lost the election to Frank Emerson by a narrow margin. Naturally, her supporters were disappointed by the surprising loss. It might have meant a severe backtracking in the way of women’s rights. Hendricks, however, took it upon herself to write a heartfelt and compelling letter to Ross after the election had fizzled.

“I feel personally,” she wrote, “in spite of defeat, that there is a good deal of comfort to be derived from participating in a campaign, for when one counts the increased information about her state, the contact with fine people everywhere, the friendships made, and above all, the knowledge gained that will be the basis for better work in the future, one must feel it is all far more than worth while.” Hendricks reminded Ross, and us all, of the true spirit of election season and all of the benefits of participating in American politics.

Sorry to report that Hendricks also lost her race as State Superintendent of Education. Hendricks remained in Wyoming until 1931, when she returned to Indiana University. Back in Bloomington, she continued with her impressive drive. As a member of the Dept. of English faculty, she went on to found the IU Writers Conference, held office as president of the Women’s Faculty Club in 1941, and made an overall remarkable impression upon our school.

Leave a Reply