Last spring, the IU Archives was contacted by a kind couple in Lafayette, Indiana who just by happenstance discovered a small but wonderful collection of WWI-era correspondence and other ephemera in a dumpster. At some point lovingly bound into 2 volumes, the nearly 300 letters between Helen Dale Hopkins and her family dating from 1915-1918 were thus thankfully saved from a fate in a landfill.

Born in 1897, Helen Dale Hopkins entered Indiana University as a freshman in the fall of 1915. She was an active member of the Classical Club, Browning Society, Pi Beta Phi, and was elected to the student honorary Phi Beta Kappa. She graduated with an A.B. in Latin with Distinction in 1918. During this period, Helen wrote home multiple times a week, predominately to her mother Clara, but occasionally also her brother Bob (Robert O. Hopkins).

Early letters report on joining Pi Beta Phi (the Pi Phi’s as she calls the sorority) and being in the library during freshman-sophomore scraps when the men were called outside and their hair forcibly cut. What we would describe as a modern-day foodie, in nearly every letter Helen reports on her meals (she seemed to have a particular fondness for potatoes and desserts), and vehemently thanks her mother for her weekly care packages of candies, cookies, bread, and wieners from home. In others she describes the contents of her friend’s packages from home, including one which included “a whole fried chicken and a fruit cake.” Other letters mention campus serenades, attending athletics events and dances, joining the Women’s League and YWCA, late night visits to the Book Nook for wieners and burgers to hear Hoagy Carmichael play, hiking to Arbutus hill, going to the Gentry Brothers Circus, student pranks such as the night she came home to a bed filled with salt, as well as campus issues such as coal shortages and the bad taste of the drinking water.

On a national level she discusses the 1916 presidential election and in the lead up to World War I she discusses military training on campus. On March 7, 1917, she describes a campus-wide meeting of all the students and faculty where “it was voted to send a telegram to [President] Wilson expressing the faith of the Indiana students in him and the promise of loyalty to the country…. President Bryan gave most wonderful talk, and several others of the faculty spoke.” Following the official declaration of war, she reports on her volunteer work with the Red Cross knitting sweaters for soldiers overseas, female students hastily marrying before their boyfriends enlisted, the dwindling numbers of male students on campus, and the back to the farm movement, which allowed students from farming families to return home to help with the crops while still earning course credit. She also alludes to the fact that Theodore Roosevelt would be their wartime commencement speaker.

One letter from April 1917 stands out in particular. While Helen mostly details daily thoughts and updates on life for her mother, she also shares the details of an incident involving a student of Russian descent (Mr. Edler). A transcript of the letter in its entirely follows.

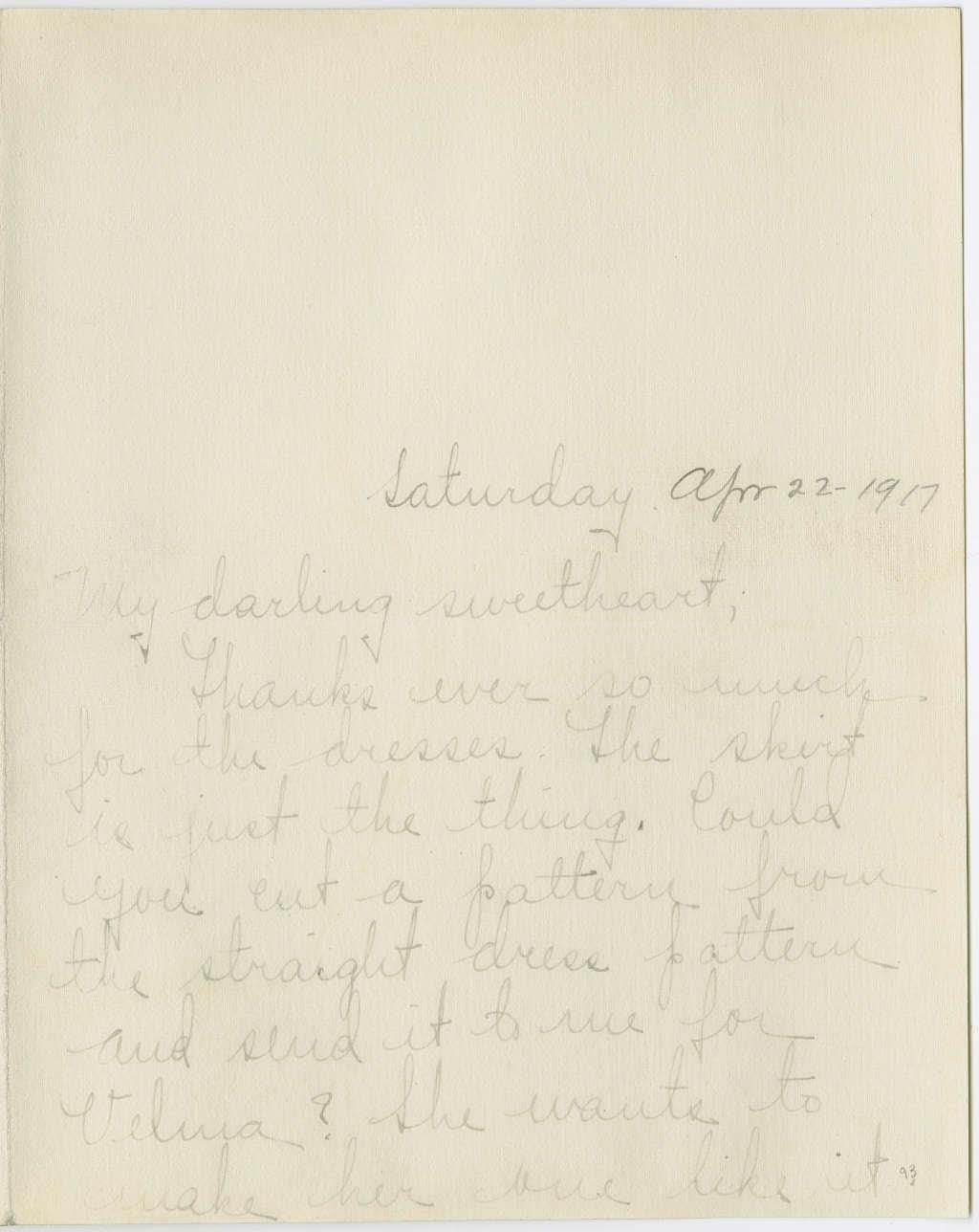

Saturday April 22, 1917

My darling sweetheart,

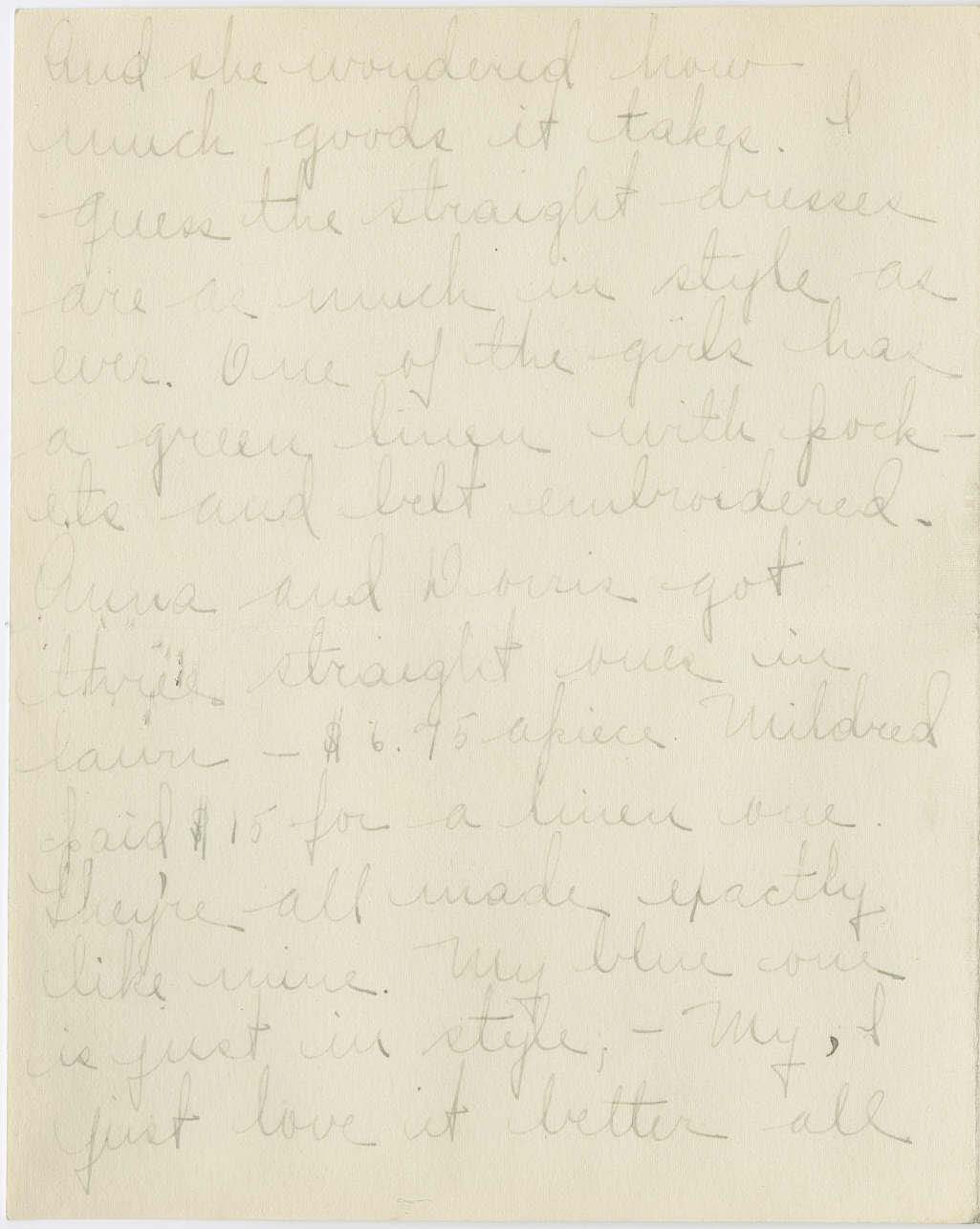

Thanks ever so much for the dresses, the skirt is just the thing. Could you cut a pattern from the straight dress pattern and send it to me for Velura? She wants to make her one like it. And she wondered how much goods it takes. I guess the straight dresses are as much in style as ever. One of the girls has a green linen with pockets and belt embroidered. Anna and Doris got three straight ones in town – $6.75 apiece. Mildred paid $15 for a linen one. They’re all made exactly like mine. My blue one is just in style, – my, I just love it better all the time. I hope it never wears out.

Louise says that if the weather is nice you and her folks are sure going to come down some Sunday. I wish you all could come some day. The campus is getting green and is full of violets and spring beauties. We were walking through it the other day and a red bird was on a limb above us and a blue bird on another branch. They were both singing and it seemed like a dream. I think the campus is the most beautiful spot there ever was.

Dr. Stout says Latin is growing more popular all the time. You know they are talking of taking German out of the schools. There are twelve in the senior class and there have been sixteen calls already for teachers. Velura is so discouraged that she broke down and cried the other day – she wants to come back so badly and everyone she talks to says that they can’t consider undergraduates for positions until all the seniors have places. Dr. Stout says that only one senior that he has known of has gotten less than $80; but he says they usually have to be satisfied with this the first year. I got all this information from being in the senior class. He put in a recommendation for each one of them.

He even wanted to know in what part of the state they wanted to teach and what sort of a school they would prefer to teach in. He said he would be glad to read the letter of application they wrote before they sent it. He seemed so interested in every one of them.

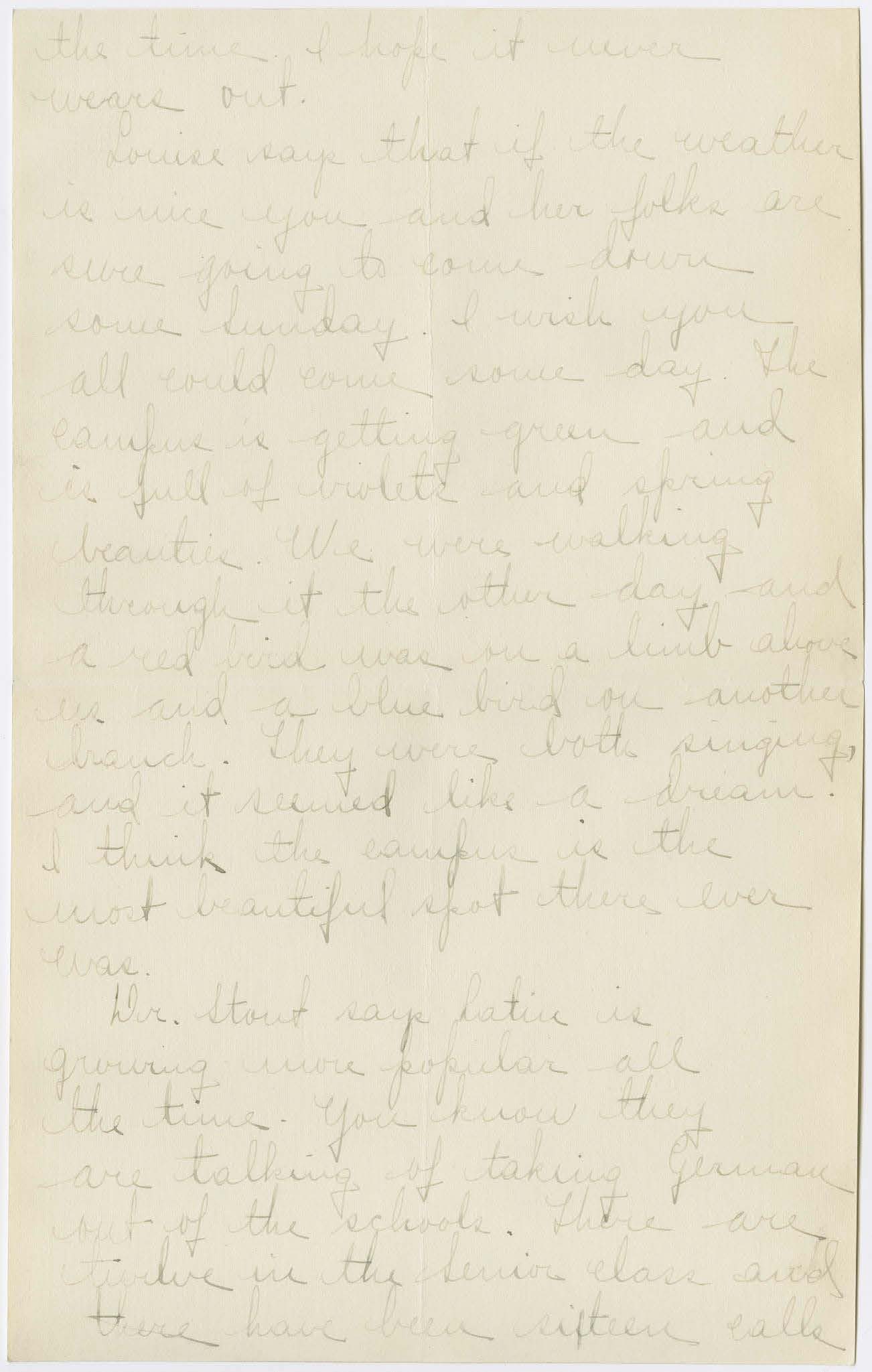

I spent the morning embroidering “Charlie” in mahogany silk on a pair of pajamas. One of the Phi Psi boy’s washing was left here and of course we thought we ought to embroider it. We embroidered hearts on all his handkerchiefs and his name on his pajamas and then cross-stitched the bottom in green and purple. Oh they were some class. I know he’ll like them. I hope so at any rate after all the work we put on them.

I’m going down a little in math. I only got 90 on the test I had Thursday. I hope we don’t have many more or he’ll find me out sure.

We decided to wait two weeks for our play, and so I don’t know what we’ll have Monday night – a good time anyway. Leah Stock, our province president, is coming Tuesday night. We’re going to move all the best furniture in our room. We’re going to have a dinner Tuesday night, a reception Wednesday afternoon, and a cooky-shine Wednesday night.

Did you see the story about Mr. Edler, a Russian in school here? He lived in a barn on two cents a day. When he was four years old, the Russian government killed his father and mother, and ever since then he has been against the government. The authorities here found his room which he had always kept locked, and found there all sorts of different mechanisms that they think he was trying to make infernal machines of. He says he was only experimenting on watches. He went around all winter without a hat and coat. He was in my Latin class, but it never occurred to me to be afraid of him. I don’t know where they’ve sent him but he’s left here.

Well sweet, I’m writing this in the midst of a stirring argument on woman suffrage; and I’m trying to argue and write at the same time.

Marie’s going to stay all night with me. Her roommate has a terrible cough, and she keeps Marie awake all night. I thought that since Louise was gone, she might sleep with me.

I went downtown with Mrs. Roberts this evening and she bought me a sack of candy. Some sport, eh?

Well sweet, I owe so many letters I guess I’d better start writing some.

With heaps and heaps of kisses,

Helen

Mr. John Edler was a Russian student at IU who earned the nickname “Hatless John” because he spent the cold Indiana winter walking around without the typical hat or coat worn by most people to protect him from the cold. According to the news coverage from April 1917, he was not a harmful individual but fellow students often heard him voicing anti-government and anarchist opinions, which raised some concerns. Finally, Registrar John Cravens and local authorities found cause and searched his room, where they discovered all kinds of mechanical parts that they assumed were being used to create “infernal machines” and bombs. Being that this was wartime, their discovery raised concerns and Edler was brought before a local Sanity Commission to judge whether or not he was a threat to the IU community and American citizens. The commission however deemed Edler completely sane and the mechanical parts harmless – in reality Edler was not in fact building bombs. He was a watch maker and his mechanisms could do no more than tell time.

After the ordeal, Edler returned to his former home in South Bend, Indiana. Tobias Dantzig, a mathematics professor at IU took responsibility for the young man, promising to assist him in finding work, which further appeased the sanity council and the whole situation was resolved.

To schedule an appointment to view the rest of the Helen Hopkins Wampler papers, contact the IU Archives.

Leave a Reply