For a vast majority of the world, 1942 was a year to remember. However, history wasn’t just being made overseas fighting in World War II; it was also being made right here at Indiana University Bloomington. During the summer of 1942, Indiana University was host to what would be the first of many Folklore Institutes. The Institute was created by Professor Stith Thompson, who had long-held the dream of bringing together like-minds from all over, both faculty and student, to meet and discuss the field of folklore; both folklore itself and the future of the field. This eight-week gathering was so successful that they continued to meet every summer.

This edition of ‘Sincerely Yours’ showcases correspondence with Herman B Wells following the conclusion of the first Institute in 1942. The first piece of correspondence comes from Jacob A. Evanson, Special Supervisor of Vocal Music for Pittsburgh Public Schools. His letter describes the success of the first Institute as “historic” and notes it as a cultural progression. This letter provides a perspective of the importance and impact of the Folklore Institute outside of Indiana University.

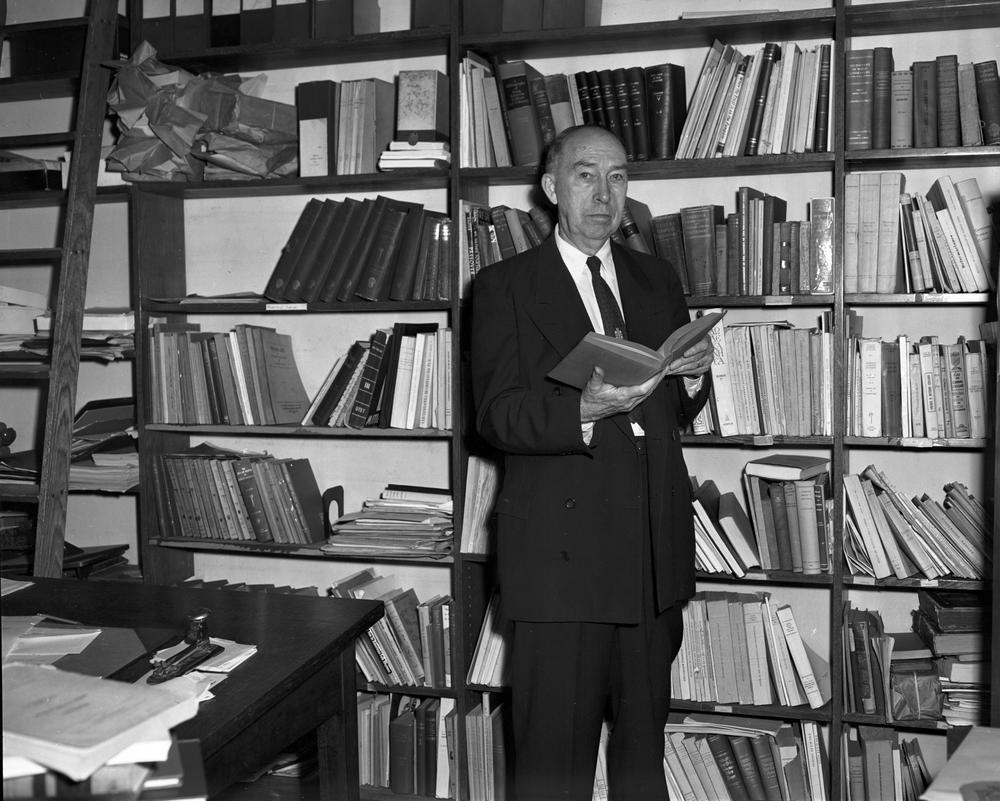

P0021913

The main correspondence is from Stith Thompson to Herman B Wells. The correspondence opens with a list of resolutions from the members of the first Institute. These resolutions include the declaration of a “permanent” Folklore Institute of America, and that the Journal of American Folklore be declared the official channel of news distribution. Also included is the Institute’s purpose statement: to bring together faculty, students, and fellow workers to create a “professionally-minded group” for study and consult not included in ordinary curricula.

This letter also contains an impassioned speech by Thompson in which he reflects on the experience of the Institute. Additionally, Thompson briefly discusses the issues at present within the field of folklore, and plans for the future of folklore in terms of professional organization, public relations, and academic development . He talks about the need for researchers to cease their reclusive ways and come together in circles like the Institute to help the field prosper through internal collaborative efforts and understanding, and by forming relations with the public. Also discussed is the implementation of proper techniques surrounding the collection and classification of folklore, from the individual collector to the establishment of a fully functional national archive.

Thompson’s description of the impact of folklore from a local to a national stage, and even a global one is captivating. He states that the support of local folklore organizations can help to further the development of larger, national folklore directives by organizations.Also addressed is the presence of folklore in the academic field. Thompson states that the presentation of folklore by universities should be done in such a way that will “infect” students and whether they be teacher, doctor, lawyer, etc., they should show interest in the traditions of their community.

Thompson closes his letter by reaffirming the purpose of the Institute by saying that research rather than teaching is the main goal, and that its value lies in its existence as the only place (at the time) to foster collaborative and individual research,and the overall growth of the folklore field.

The best part of this correspondence lies in its last few pages in the form of a poem. Nearing the closure of their time together, this group of scholars pooled their creativity to construct a retelling of events of events that they could carry with them in memory. The result of their collaborative efforts was a poem reminiscent of famous epics of the past such as the Odyssey and Aeneid. This goes to show that even heavy scholars have a humorous side, even if it may be a little high-brow.

The Folklore Institute would go on to meet yearly until the early 1960’s. It was at this time, and through the endeavors of professors Richard Dorson and Stith Thompson, that the Folklore Institute became an established department at Indiana University under the same name of the Folklore Institute. Though not in the same manner as its origin, the Folklore Institute is still present at IU Bloomington and is known by scholars throughout the world. To learn more about the Folklore Institute from its beginnings to today, visit the IU Archives in Wells Library to see the current exhibit, ‘Collecting Folklore: The History of the Folklore Institute at Indiana University.‘ This exhibit will be up until January 26th, 2018.

2 Comments

Thank you!

The Institute did not exactly meet yearly after 1942. The second time it met was in 1946. The tradition of summing up in a ballad continued; the summary notes sent to participants included “Corrido del Instituto de Folklore,” a summary song written in Mexican American corrido style by V.T.M., presumably corrido scholar Vicente T. Mendoza. Alan Lomax’s copy of the notes, as well as his own lecture notes, can be found on the Library of Congress website by searching on “Folklore Institute of America.”