Here at the Indiana University Archives, we usually blog about our more inspirational and heartstring-pulling stories. Today, though, I want to share with you a thrilling tale of daring and disaster. Our director Dina Kellams recently perused IU’s new subscription to NewspaperARCHIVE, a tremendous resource to more than 1,000 historical newspapers in Indiana. She shared a 1911 clipping from The Tribune (from Seymour, Indiana) detailing an airplane crash in Dunn Meadow here at IU.

On October 11 that year, the adventurous aviator Horace Kearney attempted an exhibition flight at Dunn Meadow. In front of a crowd of hundreds, Kearney took off and almost immediately crashed into a walnut tree. I must admit that the paper’s description of the crash put me into a fit of laughter. As someone who grew up in an era of The Simpsons and Johnny Knoxville, I have always been tickled by slapstick comedy and stunts-gone-wrong. Fortunately Kearney survived the crash (I would not have laughed if he hadn’t!), but his story shows the real dangers of aviation as entertainment. It also gives us an opportunity to see what Dunn Meadow looked like in 1911.

When Kearney came to Bloomington for his October 1911 flight, he had been flying for only two years. The St. Louis native started aviation only six years after Wilbur and Orville Wright made their historic Kitty Hawk flight in 1903. Kearney was a flier for the Curtiss Exhibition Co., a company that hired fliers and sent them on tours across the U.S. to exhibit aviation for an excited public. Fliers such as Kearney led a life of glory and possible disaster. Fellow aviator Baxter H. Adams claimed he learned to fly after he heard Curtiss was paying Kearney $600.00 per flight (more than $15,000 today). The rewards, however, came with significant risks. Baxter claimed Kearney broke fourteen bones just training to fly. An Indiana Daily Student preview for Kearney’s Dunn Meadow flight reveals:

“While flying in St. Louis in August, Mr. Kreary [sic] had the misfortune to run out of gasoline directly above a house. As he could not make an immediate descent he lost control of his machine and was hurled to the ground. He received injuries placing him in the hospital for several weeks.”

Like other daredevils such as skateboarders or BMX riders, aviators simply had to expect crashes. Obviously, though, the risk of serious injury or death was more severe for aviators. When I expressed my horror about this, University Archives photographs curator Brad Cook explained to me how biplanes were built to withstand inevitable crashes. They were lightweight enough to allow pilots to “glide” to the ground. Even so, gravity was not kind to Kearney on October 11, 1911. He came to Bloomington for Booster Day, a city celebration featuring entertainment and merchant sales. Kearney was to make two flights: one around IU’s campus and another around downtown Bloomington. The crash happened early in the first flight. The IDS described his unsuccessful takeoff at Dunn Meadow:

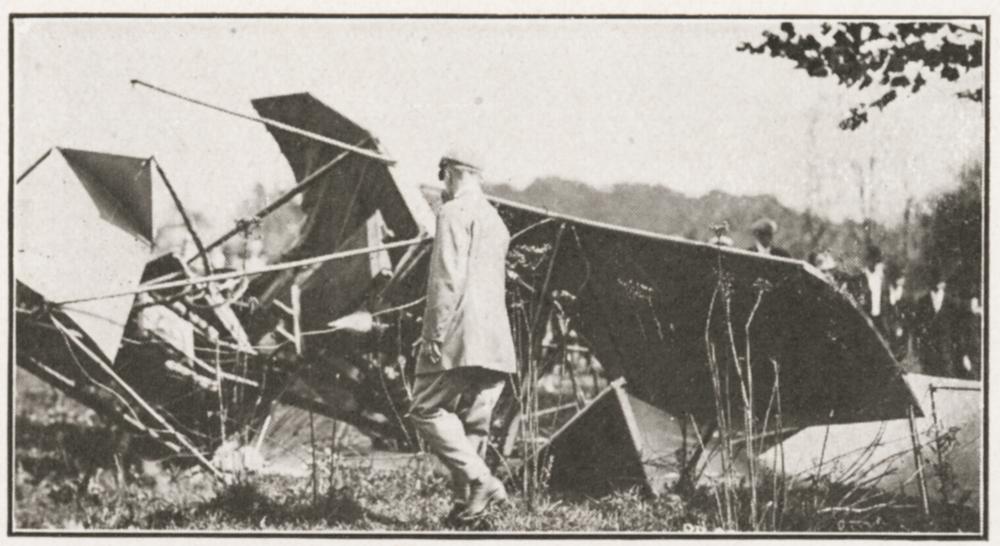

“Kearney came sweeping down the field at about forty miles an hour clip in an endeavor to get under headway, when he saw a wire fence a short distance ahead which forced him to go into the air too soon. With his attention riveted upon righting his machine, Kearney shot into the air and straight toward a walnut tree…The machine brushed against the tree and fell. Kearney was hurled to the ground, lighting upon his neck and shoulders.”

The paper continued to describe the public spectacle of the crash. The people of Bloomington rushed the crash site:

“When the machine came crashing to the ground the great crowd that had assembled to witness the flight remained motionless for a moment, and then stampeded toward the fallen man like a herd of wild cattle. Men, women, and children fought to get a sight of Kearney and the damaged machine.”

This is important because it brings me to my first point in this post: why was my initial reaction laughter? This IDS passage shows how that reaction is predicated on a history of people being wildly entertained by crash disasters. And the Class of 1912 Arbutus even made a witty goof of the event:

“October 11: The Dunn meadow aviator took a fall. About 300 students, who had previously expressed their willingness to accompany the aviator, were now glad that they had been overlooked when the invitations were sent out.”

In other words, people have been finding thrills and comedy in disaster for quite a while. So what happened to Kearney? He recovered after convalescing at a Bloomington doctor C.E. Harris’s home, he returned to St. Louis for biplane repairs (the plane itself was a total loss, but the engine and some parts were unharmed in the crash) and continued as an entertaining aviator. Tragically, but perhaps unsurprisingly, Kearney died about a year later (December 1912) in a hydroaeroplane accident near Los Angeles. Kearney and a journalist, Chester Lawrence, were found at sea shortly after they took off in a Curtiss Hydroaeroplane (affectionately named “Snookums” by Kearney) near Redondo Beach. Kearney’s death is evidence of both the extreme dangers of early aviation and the determined adventurousness of early aviators. To put his final flight in context, Amelia Earhart’s first flight across the Atlantic Ocean was not until 1928—a full sixteen years after Kearney’s final flight into the Pacific Ocean. Earhart’s final flight was not until 1937. Indiana University witnessed an extraordinarily early aviation event when Kearney flew his Curtiss biplane into that walnut tree in 1911.

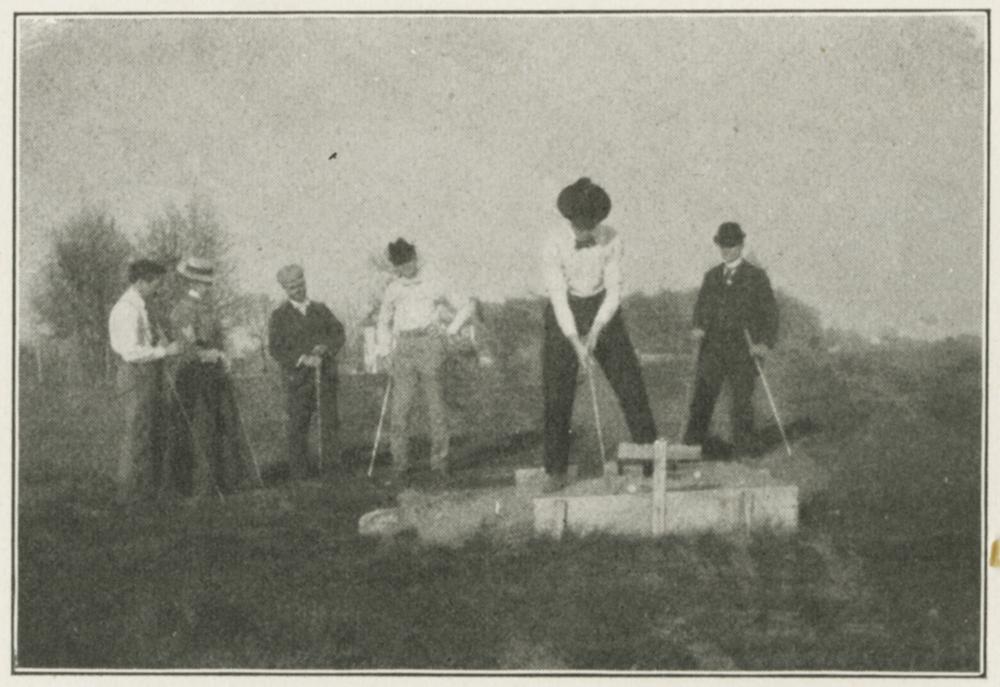

I hate to leave this post on such a morbid note, so let’s take one last look at Kearney’s amusing Bloomington flight. We can also use this event to give us some historical detail about Indiana University. Specifically, Kearney’s flight shows us what Dunn Meadow was like in 1911. I thought it was odd that Dunn Meadow could provide enough runway space for an airplane. It turns out that before the 1920’s, Dunn Meadow was much larger—it extended all the way to 10th Street. Dunn Meadow also served as a golf course at this time. Take a look below:

2 Comments

Oh my goodness, love this!

My father’s uncle was Baxter Adams. He, like Kearney were members of the “early aviators”, some of the very first to fly. Wikipedia details the requirements.

Baxter lived in Henderson, KY. My dad used to play in his plane, which was taken apart for storage and inside of a barn. (we believe now the “barn” was the Rash tobacco factory which burned to the ground taking Baxter’s plane along with it).