By Dina Kellams

September 19, 2012

Hot on the heels of Alison’s recent blog post about the 19th century Indiana University literary societies and student Homer Wheeler, I bring you another small collection – of just a single letter, in fact – which provides us with a peek into a major incident in the history of the organizations and student freedom.

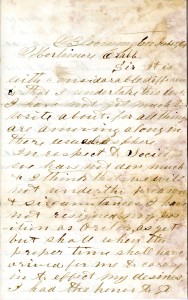

Of unknown provenance, we hold a letter student Bartholomew H. Burrell wrote to Mortimore Crabb, of his hometown of Brownstown, Indiana, on February 5, 1864. In it, Burrell relays to Crabb the troubles the campus literary societies, the Athenians and Philomatheans, were having with university administration over the level of control administration wanted to wield over the groups. Historically, the literary society halls were places where students could, within bounds, feel free to express themselves. However, due to a series of incidents the Board of Trustees became involved and adopted resolutions that placed restrictions on the group, including the requirement that the faculty were to approve any outside speakers the students wished to bring in.

This happened at a time in higher education when the idea of in loco parentis – “in place of a parent” – was firmly in place. That is, in the absence of parents, university faculty and administrators were expected to make decisions that were considered to be in the best interest of the the students. That being the case, it was not unheard of that university administrators sought to place restrictions on the students. What was unusual in this case was the response of the students.

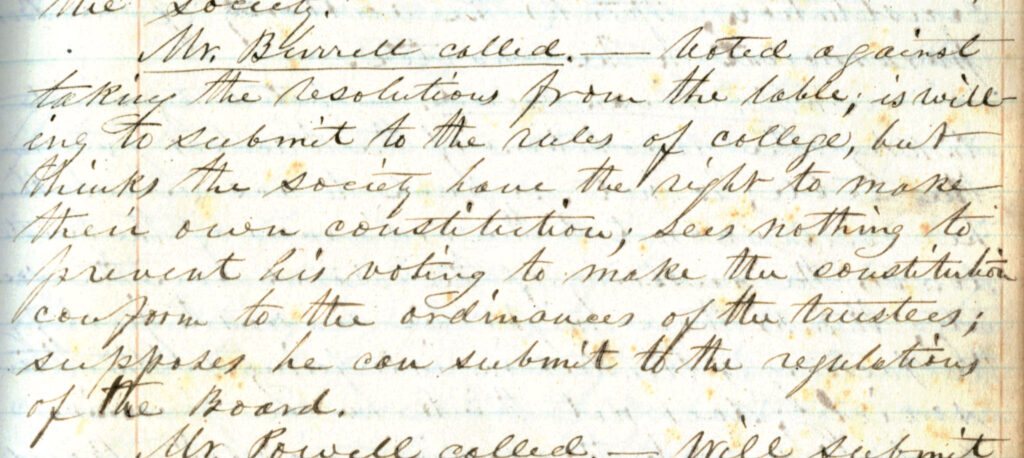

Members of the literary societies objected vehemently to the Trustees resolutions – of which the exact wording is unknown, as Trustees minutes spanning 1859-1883 were lost in the 1883 fire. They argued their charters came directly from the Legislature and as such, their activities were outside the realm of the administrators. December 18, 1863, the Philomatheans sent a list of resolutions to the faculty, which included this strong statement, “We deem it our duty to treat with respect any recommendations or requests made by those who have control over us as student of the University, and whose duty it is to labor for our interests, but that we respectfully ask them to respect our rights….” The record indicates the faculty discussed the Philo’s resolutions before firing back with their own resolutions which stated, in a nutshell, that they did not believe the Legislature ever intended the charters to supersede the authority of the faculty and administration.

With seemingly indefatigable determination, the students continued the fight and talked about moving off campus, dissolving and forming new groups, etc. The nearly year long fight came to a head on February 5, 1864 – the same date of Burrell’s letter – when a small group of Athenians “broke” into Athenian Hall to hold its regularly scheduled meeting. Charges of trespassing, forcible and unlawful entry, and riot (and stealing oil to heat the room during the meeting!) were brought against those involved.

This first important fight of student rights is painstakingly documented in the faculty minute books. While the students finally acquiesced, they had the last word. Following the rules set in place, they did put forth the name of their invited Commencement speaker – one William Mitchell Daily, former IU President. Would seem a good choice, yes? It probably would be, if not for the fact that Daily had resigned from the presidency in 1859 amidst a scandal and upon his departure, called the faculty “a set of pusillanimous, narrow-minded bigots.” The faculty discussed this choice and upon learning the Societies had already informed Dr. Daily of their decision, they approved his visit. “But,” they wrote,

they think it their duty to call your attention to the fact that in future a compliance with the Ordinances of the Board of Trustees will require that you should send in the name or names for approval before sending out the notice and they consider that it would be yet better, and would save all parties trouble, if you would hand in a list of names for approval before proceeding elections.

To read more about this particular incident, see Thomas Clark’s Indiana University: Midwestern Pioneer, Volume 1. And finally, keep an eye out, the Digital Library Program is currently scanning the entirety of the Faculty minutes, which spans 1835-1964 and includes details of this moment on IU history!

Leave a Reply