The Eagleson family has been in the local news lately, with the renaming of Jordan Avenue through campus for the prominent Black Bloomington family. Below is a shortened version of an earlier story written for volume 2 issue 2 of 200: The Bicentennial Magazine about one of the family members and IU alums, Preston Eagleson (see here to read the full story)!

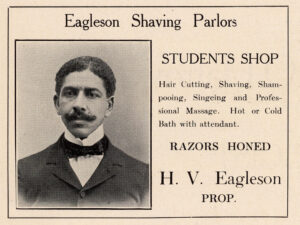

The Eagleson name is familiar to many at Indiana University and in Monroe County, as the prominent African American family is riddled with “firsts” and other high-level achievements, dating back to patriarch Halson V. Eagleson, Sr., a successful barber in town in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Today’s story turns to Halson’s son Preston, born in Mitchell, Indiana, in 1876.

During his earliest years, Preston’s family moved around throughout southern Indiana and St. Louis. According to one source, the family settled in Indianapolis about the time he was to enter high school but “his father needed his services” and as a result, Preston worked for a year in the print office of The World, an Indianapolis-based African American newspaper. He then went on to work for the Griffith Brothers, a wholesale millinery firm in Indianapolis before finally entering high school in 1889 when his family settled in Bloomington. At just 16 years old, Preston graduated second in his class from Bloomington High School in 1892.

Preston enrolled at Indiana University, entering as a freshman that fall. A skilled athlete, he became the first African American to participate in intercollegiate athletics at IU when he joined the football team as a freshman. (Yes, my research turned up stories of him playing in 1892, a full year earlier than previously thought!) Newspaper accounts identified the young player as a standout on the field and Eagleson continued as a major force on the team for the remainder of his undergraduate career.

When Preston began at IU, there were only 10 years between him and IU’s first known African American student, Harvey Young, who entered in 1882. However, Indiana University still had not seen a Black graduate from the institution. While Eagleson was not the lone person of color on campus, his presence may have drawn some attention from the all-white faculty and pre- dominantly white student body. There is no evidence, however, that he faced any sort of prejudice on campus or from his teammates on the gridiron, but the same cannot be said of the team’s road trips.

In October 1893, the Hoosiers traveled north where they were scheduled to face off against Butler University. According to newspaper accounts, everything that could go wrong with this trip and game did. To start with, Butler did not greet the Hoosiers at the train station and the team had to find their own way to their overnight accommodations. Butler, in charge of said accommodations, reportedly put the IU men up in a “second class hotel.” The day of the game, the hosts did not arrange for a hackney (a horse-drawn carriage that served as a taxi) so the players had to take a streetcar that dropped them a great distance from the field, necessitating a long walk with equipment in tow. And, of the game itself, the Indiana Student (known today as the Indiana Daily Student) reported unfair calls, field brawls, and the crowd shouting racist expletives at Eagleson.

Eagleson’s race, sadly, became an issue once again the following year with dramatic results. On October 30, 1894, the Indianapolis Journal published this headline:

“AGAINST THE COLORED PLAYER: Two Hotels in Crawfordsville Refused to Take in an I.U. Man”

Indeed, when the IU football team traveled north to take on Wabash College, the proprietor of the Nutt House, upon learning one player was Black, would not accommodate the team unless they agreed to dismiss Eagleson. His request was met with refusal and the group went to another inn, where they were met with the same response. A third innkeeper, however, welcomed the entire team and they found board and lodging for the night. The incident, however, infuriated Eagleson’s father, Halson, and the next day the newspaper reported Halson planned to sue the two unaccommodating hotels under Indiana’s Civil Rights Act.

In 1885, Indiana passed a Civil Rights Act that stated all persons were “entitled to the full and equal enjoyments of the accommodations, advantages, facilities and privileges of inns, restaurants, eating-houses, barbershops, public conveyances on land and water, theaters, and all other places of public accommodations and amusement.” Punishment for violations were up to $100 fine and/or up to 30 days in jail.

Preston’s father apparently did not initially know about the monetary limit, as the newspapers reported he intended to sue both parties for $5,000. Inexplicably, later reports dropped any mention of the second inn and ultimately, it was only the Nutt House and owner J.B. Fruchey named in the suit filed December 12, 1894.

The case was heard in the Montgomery County circuit court on January 29, 1895. The Crawfordsville Journal was on site to report to its readers. In their summary of the situation, the reporter states that innkeeper Fruchey had “agreed to allow Eagleson all the best the house had except the privilege of eating in the dining room. This, they said, they could not do, as their white patrons, traveling men, vigorously objected to eating in the room with a negro and threatened to leave if he was brought in.”

The jury deliberated throughout the night. On the first ballot, nine voted for Eagleson, three for the defendant. By the fourth ballot it was unanimous for the plaintiff but then there were deliberations over the damages. Eight jurors voted to award Preston the full $100 allowed, while the paper identifies two jurors, Messrs. Allen Robinson and Sam Long, who voted for one cent. Eventually they came to a compromise of $50, equivalent to just over $1500 today. Fruchey reported immediately that he planned to appeal. In March 1896 the case was reviewed in the Appellate Court of Indiana but the court affirmed the decision for Eagleson.

There were no other known incidents during Preston’s time at Indiana University. He continued as a leader on the football field and also proved himself an outstanding orator. During his junior year Eagleson won the right to represent Indiana University at the State Oratorical Contest, the first African American student to appear at the contest. There, he came in fourth place with his original address on Abraham Lincoln. Preston earned his bachelor’s in philosophy in 1896, graduating one year after Marcellus Neal, IU’s first Black graduate. He immediately began work on his graduate degree and through periodic enrollments, in 1906 he became the first African American at IU to earn an advanced degree with an MA in philosophy.

Despite earlier newspaper reports that Eagleson aspired to become a lawyer, he became a teacher, moving around between St. Louis, Indianapolis, and South-Central Indiana. At one point, Eagleson even taught at Indianapolis Public School #19, where fellow Black IU alumnus Marcellus Neal was principal.

Eagleson’s life ended tragically young and he died at home in 1911 at the age of 35. Of his death, the Bloomington Daily Telephone noted he had been in poor health for years and had sought treatment in both Indianapolis and Madison before coming home for his final months.

Many thanks to Cindy Dabney, Outreach Services Librarian at the Jerome Hall Law Library within the Maurer School of Law, for her assistance in locating–and explaining–19th century cases and laws.

Leave a Reply