The Electropoise was a fraudulent medical device invented and patented by huckster Hercules Sanche, the self-proclaimed “Discoverer of the Laws of Spontaneous Cure of Disease.” Initially marketed in the early 1890s (sources differ on the exact date), it was the first of several devices that provided “gas pipe therapy,” and its story provides an interesting portrait of late 19th –century American alternative medicine, the power of advertising, and the potent mix of gullibility and desperation that allows quack cures to flourish.

There is nothing electric about the Electropoise, and the “Plain Directions” (which are actually anything but plain) that accompany the object tell its user, “Do not expect any sensations of current or shock. Nature does not work that way.” The Electropoise is simply a brass lozenge called the “Polizer” to which is attached at one end a flexible uninsulated cord. At the end of the cord is a small metal disc with an elastic band, which the user attaches to her ankle for a general cure or to whatever part of the body ails her for specific therapy. The user is directed to put the tube in a bucket of cold water (the exact temperature of the water and the amount of time for the therapy being determined by a complex series of disease classifications and formulae) and then let healing oxygen flow through the cord and into the body. The instructions claim that “[t]he oxygen … is carried into the general circulation and oxidizes the blood, thus burning out all manner of poisonous impurities, destroying bacteria and preventing their further propagation.” Of course in reality, the Electropoise did absolutely nothing at all. Its makers relied on the principle that a portion of those who are sick – and, more importantly, those who believe they are sick – will get better without any treatment. A contemporary promotional feature in an 1894 issue of The New York Evangelist promises that the Electropoise could cure “an alphabet of ailments” from abscesses to vertigo. The brochure that accompanies the instrument includes seventy pages of testimonials from satisfied customers who believe they have been cured of headaches, insomnia, “female complaints,” rheumatism, malaria, pneumonia, paralysis, nervous disorders, consumption, and cancer. The directions include further serious ailments that the device is supposed to cure; for example, they advise that sufferers of “apoplexy, apparent death, congestion of the brain … drowning and epilepsy” can be aided by “chang[ing] the plate from one wrist to the other every twenty or thirty minutes during continuous application.”

According to an advertisement in an 1895 issue of The Cosmopolitan: A Monthly Illustrated Magazine, the cylinder is filled with, “a composition, the nature of which is not made public.” In the December 1, 1900 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association, N.C. Morse, M.D. writes, “I have had it sawed into sections and alas, like the goose that laid the golden egg of fable fame, there is nothing in the carcass!” However, despite its literally hollow claims, the Electropoise was very popular, so much so that the Electrolibration Company, founded in Birmingham Alabama, soon added offices in New York and London and began marketing new devices such as the Oxydonor, which was the same as the Electropoise except that instead of being hollow, it contained a stick of carbon inside. Other companies followed with their own versions. In 1899, Sanche tried to prevent the sale of the rival Oxygenor but it was held by the court that there was insufficient evidence to show that Sanche’s invention was useful or valuable enough to be afforded protection. The American Medical Association released official statements, such as a 1915 book on “Mail-Order Medical Fraud,” condemning this kind of ersatz medical treatment.

As well as being potentially dangerous, the Electropoise was also expensive. Advertisements from the period indicate that this model of the Electropoise was priced from $10 to $35. The booklet included with the Lilly Library’s copy lists the price of the pocket model as $25 and the standard model (a large device which was mounted on a wall) as $50. This may sound like an inexpensive cure for all ills, but $25 at the turn of the century was comparable to several hundred dollars today. The testimonials included in the literature make it clear that consumers could pay in installments. The two books included with the Lilly Library’s copy of the Electropoise are undated. The book which includes testimonials has the name L.A. Bosworth on the cover, and many of the testimonials are addressed to him in the form of letters. Bosworth was a reverend in Boston, MA, but his connection with Sanche or the Electrolibation Company of Birmingham is not clear.

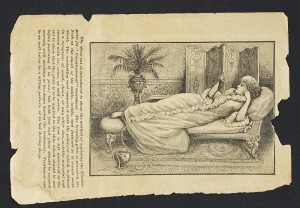

So who used the Electropoise? The illustration included in the literature that accompanies the device gives us a clue. A woman in the “Gibson Girl” style lounges prone on a settee, reading a book while the cord of the Electropoise snakes delicately from her ankle into a vase on the floor. This woman in her lacy dressing gown is the perfect consumer for the product. She is clearly of the middle or upper-middle class and she has leisure time in which to convalesce. While the testimonials reveal that both men and women used the product, it would have been especially appealing for vague “female complaints” or the ubiquitously-diagnosed condition of “hysteria” – in other words the types of ailments that may well be “cured” by a device that doesn’t do anything except make the sufferer believe that he or she will get better. The Electropoise enjoyed its reign of popularity at the same time that the vibrator was invented to “cure” hysterical women by means of genital massage – a method practiced manually by doctors and midwives since the times of Galen and Avicenna and brought into the age of electricity in the late 19th century by enterprising inventors who aspired to save doctors the trouble of inducing “hysterical paroxysm” manually. In the Paris Exposition of 1900, over a dozen medical vibratory devices were available for the perusal of visiting doctors, from low-priced foot-powered models, to the $200 elaborately-designed “Chattanooga.” The Electropoise was perhaps a distant cousin of these devices designed to cure hysteria, the great bugaboo of 19th-century medicine, a catch-all for everything from serious mental illnesses to boredom and sexual frustration. The instructions for using the Electropoise includes a section for female complaints and advises that “[i]n many cases the internal female generative organs can be treated more successfully by local application to the organ itself. For this purpose the Uterine Electrode [a long metal rod that could be attached to the device] should be used. Agents can furnish it. Price, $2.50.” Specific male complaints, including hydrocele, varicocele, and “self abuse” could be treated by applying the metal disc to the scrotum. In its promise to provide relief to even the most intimate of problems, bypassing the process of visiting a real doctor, this curious little device illustrates the allure of quack medicine and is not so different from placebo products shilled on late night infomercials today. There will always be a market for the phony miracle cure.

Rebecca Baumann, Reference Associate

Sources Consulted:

American Medical Association. Medical Mail-Order Frauds. Chicago: American Medical Association, 1915. Hathi Trust Digital Library.

“The Electropoise.” New York Evangelist. December 6, 1894. ProQuest American Periodicals.

“The Electropoise.” The Cosmopolitan: a Monthly Illustrated Magazine. 1895. ProQuest American Periodicals.

Rachel Maines. The Technology of Orgasm : “Hysteria,” the Vibrator, and Women’s Sexual Satisfaction. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999.

N.C. Morse. “Modern Empirical Inventions.” The Journal of the American Medical Association. Volume 35, part 2. December 1, 1900. Hathi Trust Digital Library.

Carolyn Thomas de la Peña. The Body Electric: How Strange Machines Built the Modern American. New York: New York University Press, 2003.