By Lindsay Weaver, Intern, Lilly Library Technical Services

The Lilly Library is currently cataloging an exciting collection of music once owned by Marie-Caroline de Bourbon-Sicile, Duchesse de Berry (1798-1870), an important political figure in France during the nineteenth-century as well as a generous patroness of the arts.

One of the most intriguing items in the collection so far is a slim funereal volume bound in black morocco with silver fleur-de-lys stamped on the spine. If the Duchesse were a heroine in a novel, this item more than anything else would represent the tragic climax of her origin story. Inside are twenty-five pieces of printed music pertaining to the murder of her beloved husband, which occurred 197 years ago this week on 14 February 1820.

Marie-Caroline married Charles-Ferdinand d’Artois, Duc de Berry, at Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris on in June of1816. Despite their arranged engagement, a genuinely affectionate romance blossomed. Said to be inseparable, they strolled arm-in-arm in the public gardens of the Tuileries and scandalized the royal family by addressing one another in the familiar “tu” rather than the formal “vous.”

This, unfortunately, was not to last. On the evening of 13 February 1820, the Duc and Duchesse de Berry arrived fashionably late to the Opéra. Though an avid theater-goer, Marie-Caroline was exhausted and wanted to leave early. Unknown to Paris at large, she was three months pregnant. Charles-Ferdinand, ever the dutiful husband, escorted her to their carriage but wished to see the remainder of the performance. His decision to stay turned the evening from a diary footnote to history book fodder. As the Duc turned away from the carriage, an anti-monarchist called Louvel plunged a knife into his back and ran. The wounded prince was carried into an administrative office in the opera house where he died in the early hours of the morning with Marie-Caroline weeping at his side, covered in his blood. For over a month after the assassination, she sequestered herself in an apartment draped in black cloth.

A widow at twenty-two, they had been married less than four years.

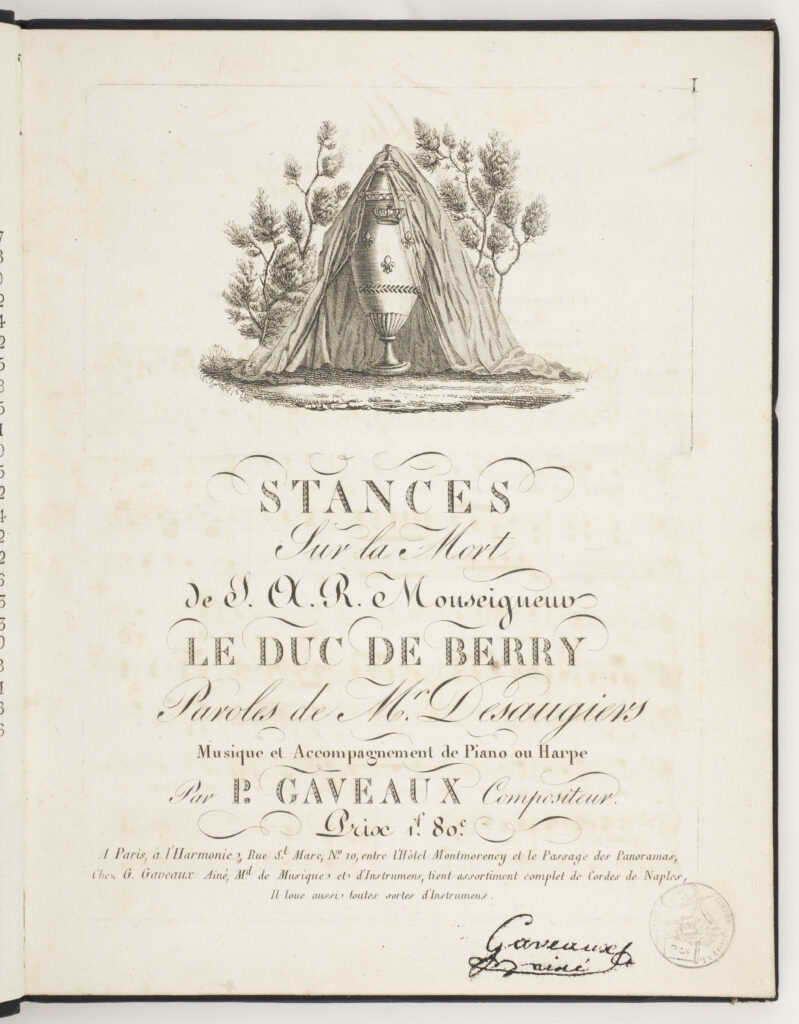

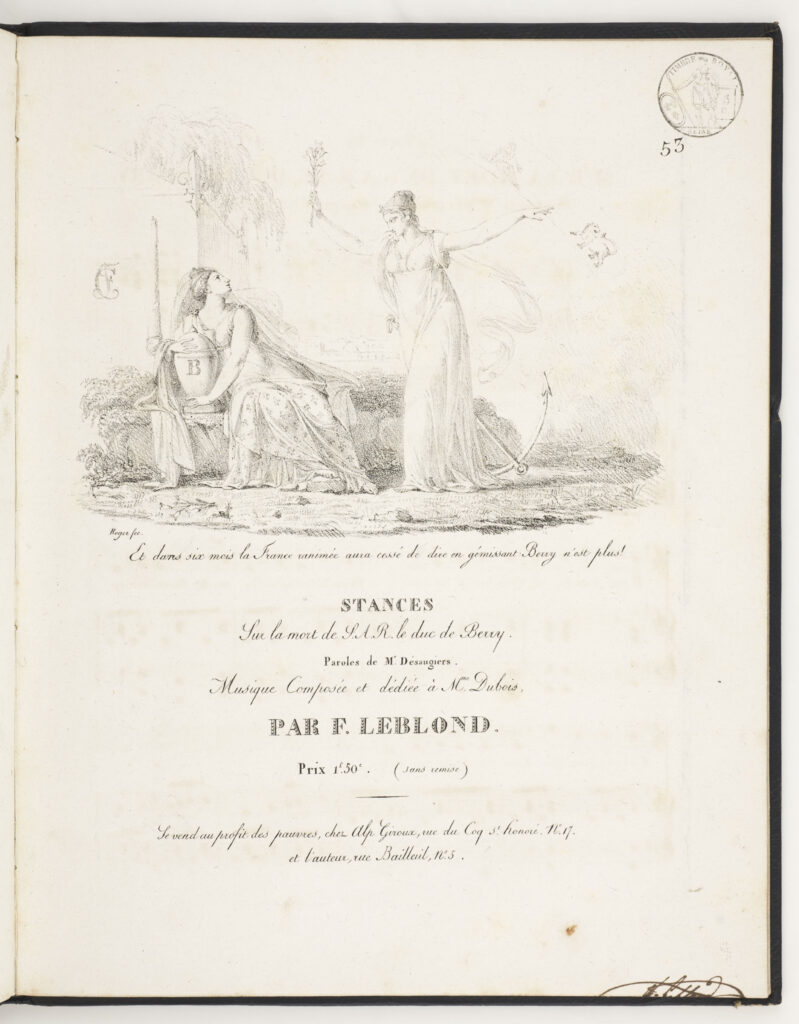

Collections of music such as this one are fascinating pieces of history and offer rich insight into those who created them. Of the twenty-five songs contained in this volume, all but five are settings of a text entitled “Stanzas on the Death of His Royal Highness, Monseigneur Duc de Berry” by Marc-Antoine Désaugiers, then the director of the Théâtre du Vaudeville. The poem, which solemnly enumerates the Duc’s good qualities, ends on a hopeful note by declaring Marie-Caroline’s unborn child the future relief of France’s mourning. The words may have brought her comfort.

The contents also suggest something about her social circle during this time. Composers of personal importance are represented more than once: there are two works by her harp instructor, François Joseph Naderman, as well as two by Ferdinando Paër, her singing teacher. (And while this volume is not an exhaustive collection of all settings of Désaugier’s “Stances,” notably missing is a popular one by Paër’s rival, Gaspare Spontini.) Paër also appears as the musical intermediary between other composers and the Duchesse—three songs are marked as having been “offered to M. Paër by the music’s author.” Other pieces bear faint creases, clearly having been folded into quarters prior to binding, as though offered in passing to the Duchesse who tucked it away.

Lastly, multiple pages bear annotations, suggesting this was not passive, dutiful acquisition. There are penned annotations marking articulation or supplying missing accidentals, suggesting the Duchesse had engaged with this music. Given much of it is for soprano voice with piano or harp accompaniment, this seems likely: the Duchesse was reportedly a talented musician, especially on the harp.

This is only one of many interesting items at the Lilly Library relating to the musical life of the Duchesse de Berry and should prove an interesting collection to anyone interested in the music-making of women during the Bourbon Restoration.

References:

Margadant, Jo Burr. “The Duchesse de Berry and Royalist Political Culture in Postrevolutionary France.” History Workshop Journal 43 (Spring 1997): 23-52.

Reiset, Vicomte de. Marie-Caroline, Duchesse de Berry: 1816-1830. Paris: Goupil & Cie, 1906.

Skuy, David. Assassination, Politics, and Miracles: France and the Royalist Reaction of 1820.

Lindsay Weaver is a master’s student in library science with a specialization in Music Librarianship. Her research interests revolve around the the opera world in Paris during the nineteenth century. Currently an intern with the Lilly Library Technical Services Department, she hopes to work in a special collections library one day.

2 Comments

Wow Nice Article Sharing………Im Happy

I so enjoyed the information and the humorous content of this post! Thanks Lindsay for your engaging story-telling and insight about this item!