Given Madeline Kripke’s love of English slang and English dictionaries, we reasonably expect to find copies of all the major (and many minor) English slang dictionaries in her collection, including some of the earliest. When the four volumes of Julie Coleman’s monumental A History of Cant and Slang Dictionaries appeared (2004–2010), Madeline probably combed through them to discover both what slang dictionaries she already had and which she would need to acquire. The short catalogue of her collection, roughly 6,000 items, confirms that she owned all four volumes, and she refers to them in catalogue entries for other books.

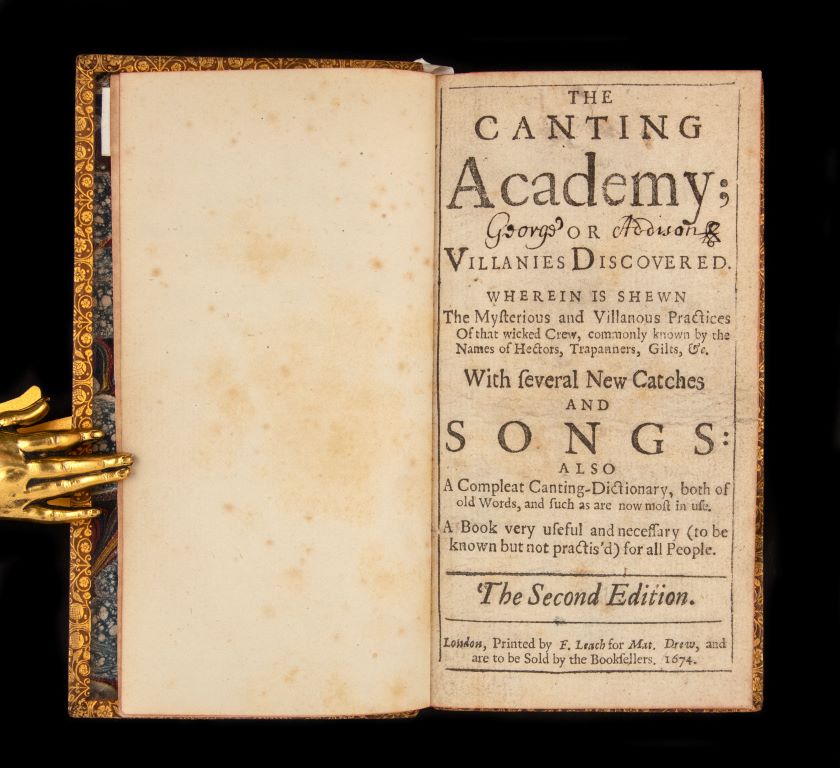

It comes as no surprise, then, to find Richard Head’s

The Canting Academy

or

Villanies Discovered

Wherein is Shewn

The Mysterious and Villainous Practices

Of that wicked Crew, commonly known by

The Names of Hectors, Treppaners, Gults, &c.

With several New Catches

and

Songs

also

A Compleat Canting-Dictionary, both of

Old Words, and such as are now most in use

in one of the first boxes we unpacked.

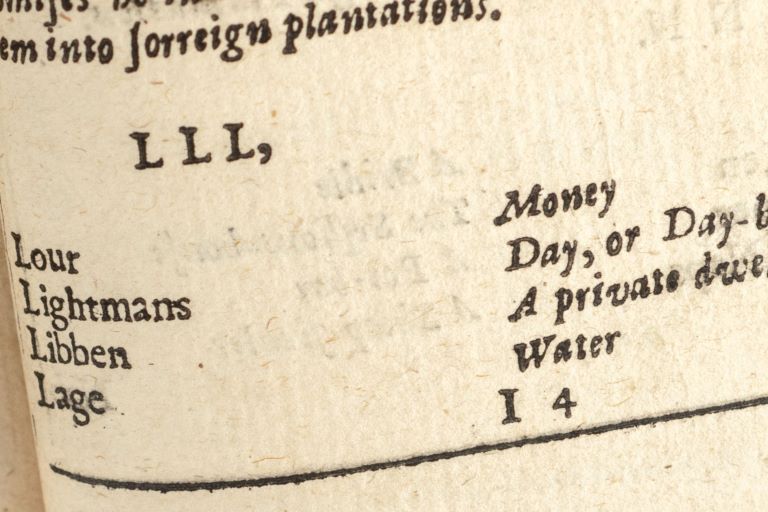

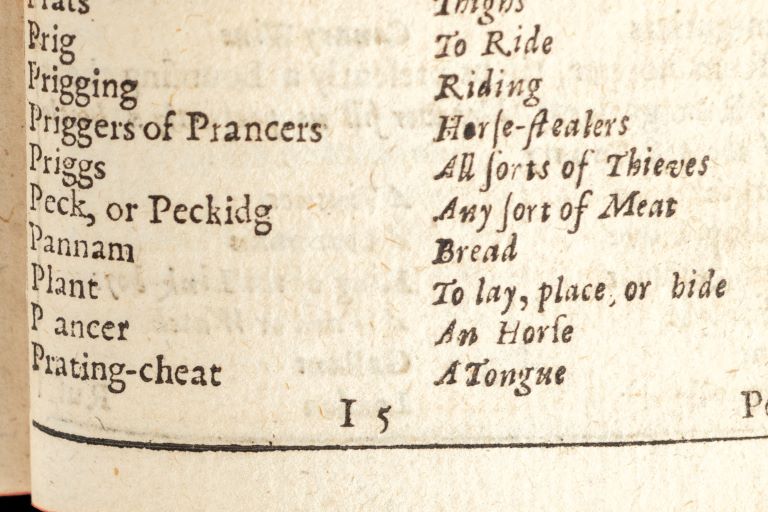

Head’s book is an exposé of criminal practices and the language with which criminals cloak their comings and goings and daggers. The dictionary portion of The Canting Academy includes terms such as plant “To lay, place, or hide,” still current in English and no longer restricted to criminal jargon, but also words like libben “A private dwelling house” and milken “An house breaker,” both of which had petered out by the twentieth century and never entered everyday English. The Canting Academy includes two word lists, one from cant to English and the other from English to cant, functioning then as a sort of bilingual dictionary, though one wonders how many who owned it looked up hat to find that criminals would say Nab-cheat among themselves.

Head’s lists of cant words, which he attributes to “Gypsies,” proved influential. First published in 1673 — the Kripke Collection may include the first edition, but the copy in question here stands for the second edition of 1674 — The Canting Academy’s word lists, cant to English and English to cant, were between them published 33 times between 1673 and 1780 and borrowed by other authors, as well. Coleman distinguishes “The Head-lists” as a significant textual tradition in early English lexicography and treatment of slang.

Madeline’s copy of The Canting Academy contains an unusual amount of other commentary besides the text, what some would call paratexts. For instance, we know the book, which would have been sold in loose sheets, was bound by one W. Pratt. If this was the bookbinder William Pitt Pratt (1783–1838), who flourished from 1823 to his death, then Madeline’s copy was bound rather late, or an earlier binding was replaced — determining which is on my long list of things to figure out about the Kripke Collection. Madeline bought her copy at the “[John] Brett-Smith sale, Sotheby’s Marlborough Bookstore, London, 6/05 for £1800” — not the biggest price she ever paid for a dictionary, but substantial enough to make this copy of The Canting Academy a prize.

Brett-Smith (1918–2003) was a book collector extraordinaire who was the son of another, best known for his carefully curated stock of Restoration drama, now in the Cambridge University Library (see the obituary by Stephen Ferguson in the Princeton University Library Chronicle [2003]). In a separate note, Brett-Smith wrote, “This second edn is completely reset, and substantially rearranged from the first edn. Most of the contents are identical” — Coleman confirms this — “but there are some omissions and some additions of whole passages or sections.” His comment balances the book’s content — its authorial information and ideas —with its structure and material presence. Just this one copy of one book reveals a truth: books are more complex than their contents, and copies of books further complicate the books they represent.

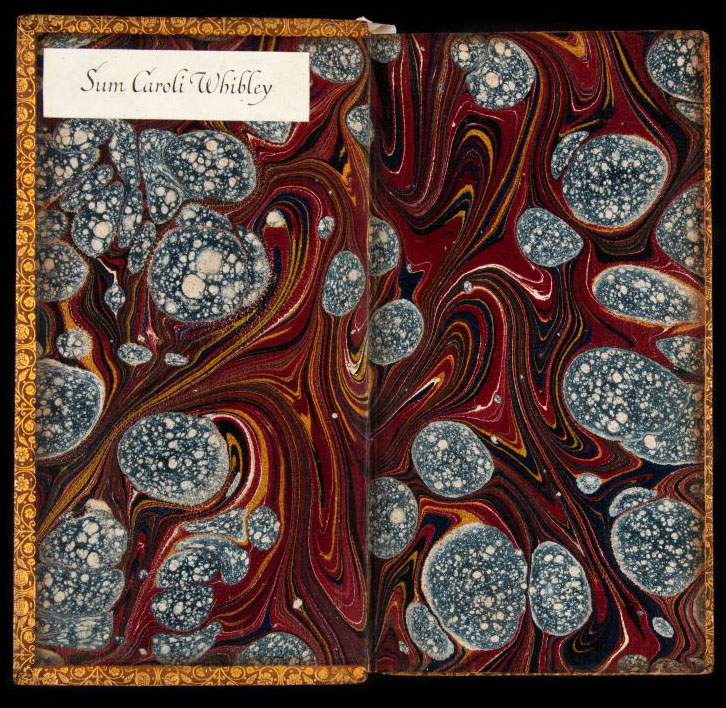

Of other paratexts within Madeline’s copy of The Canting Academy, one is intriguing and the other of some historical importance. On either side of the “or” in the second line of the title, a certain George Addison has signed his name. (I haven’t yet identified the George Addison in question — suggestions are welcome.) A plate places the book in the library of Charles Whibley. According to T. S. Eliot, Whibley’s monthly contributions to Blackwood’s Magazine, thirty years of them, constituted “the best sustained piece of literary journalism that I know in recent times.” Whibley was a notable figure, and his ownership of Head’s volume says something about his cultural interests and reading tastes.

His ownership of the book is even more important in the history of lexicography. Whibley was for several years associate editor of the Scots Observer, whose editor at the same time was W. E. Henley. For students of slang, dictionaries, and dictionaries of slang, however, the Scots Observer is hardly the relevant work. With John S. Farmer, Henley compiled six of the seven volumes of Slang and Its Analogues (1890–1904) — a work amply represented in the Kripke Collection — and, however coincidental it may be, that Whibley owned an important early slang dictionary suggests common ground beneath their friendship, perhaps influence in one direction or another.

The Canting Academy is a rich resource for lexicographers and historical criminologists, but clearly in collecting it and other important slang dictionaries, Madeline sought added value of various kinds, including book historical matters of binding and sales and collations of editions. Addison’s signature and Whibley’s book plate draw the book from a library shelf into a human dimension, one in which the book was collected at least four times by people to whom it mattered as information or as an artifact or both. As evidence of culture, Madeline’s copy of The Canting Academy exceeds the text: the various collectors have added their interest in the book to the book — indeed, to this copy of the book — in various material ways. In such cases, it’s reasonable to judge the book by its cover and by other items glued to the end papers, as well as for the material printed on its pages.

Leave a Reply