By Brandis Malone

Brandis Malone is a second-year master’s student in the dual Russian and Eastern European studies and Library Science program at Indiana University.

When I first found out about these posters a few months ago, I really didn’t know what I was getting myself into. The box was massive, took two people to move, and viewing them in the reading room took up an entire table, which is no easy feat. Each poster within was beautiful, and the previous owner had painstakingly written out English translations on several labels and affixed some of the most fragile pieces to large sheets of cardstock. Though we don’t know much about them, we do know that they were transferred over from the government document collection at the Herman B. Wells Library over 20 years ago. While they have been used for teaching and research, we’ve only just recently had the opportunity to update their catalog record to truly reflect the materials. This collection of Soviet propaganda consists of 32 posters of varying sizes and topics, published from about 1928 to 1930. They reflect the efforts of the Soviet Union during the early 20th century to spread the Party ideology, promote certain policies and goals, and display the ideal future Soviet utopia.

Almost all of these posters were published by the State Publishing House. Based in Moscow and Leningrad (modern-day St. Petersburg), the goal of this publishing house was to unite the Union’s printing and publishing efforts. Posters were created by a variety of different artists who sent in their designs, and once approved they were then produced in bulk, with tens of thousands of copies printed in a single run.

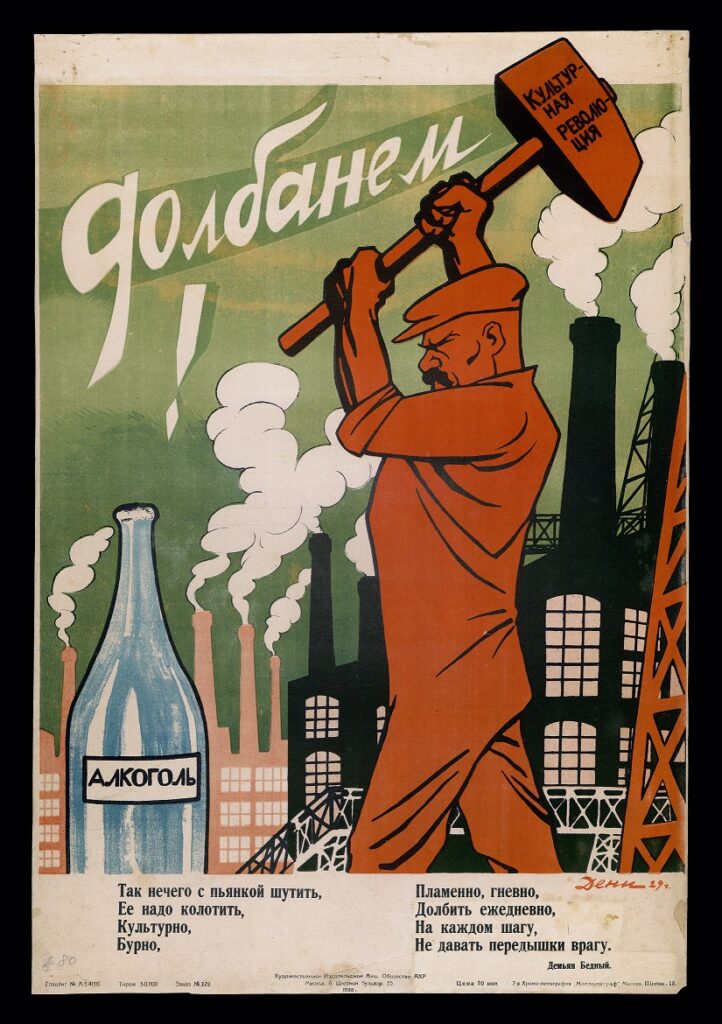

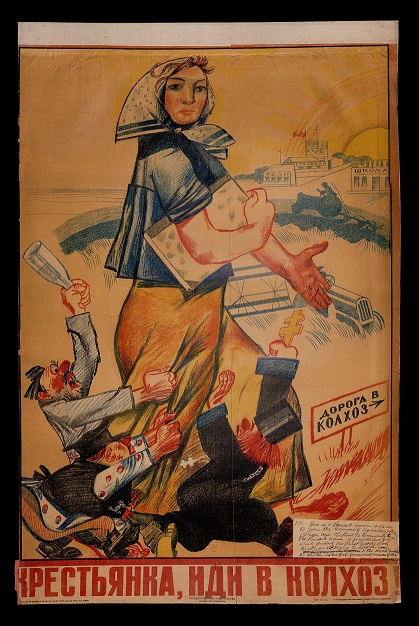

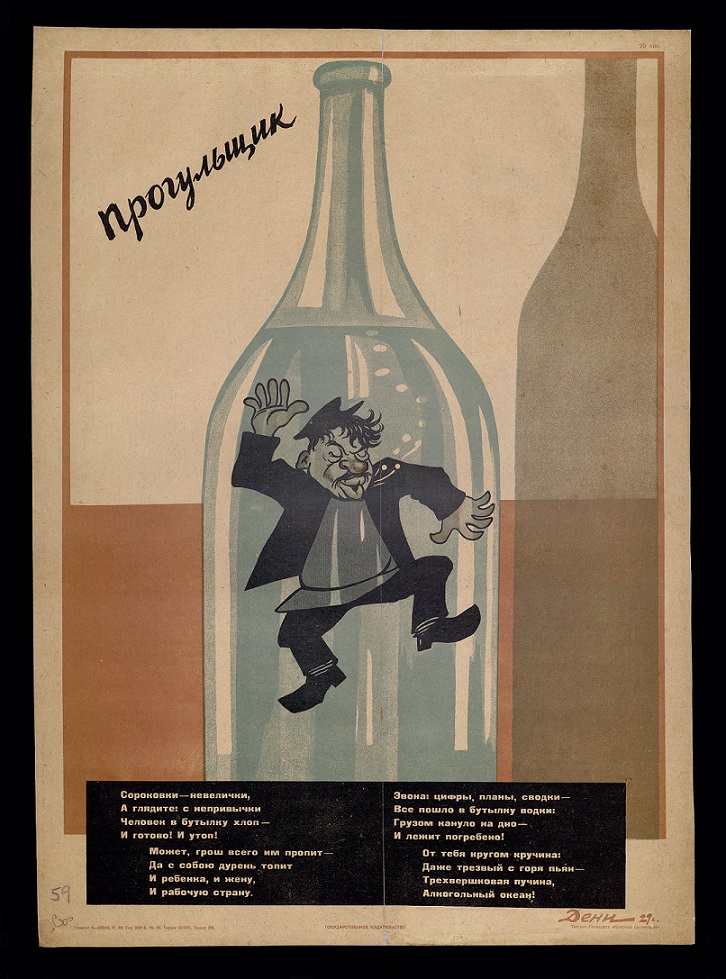

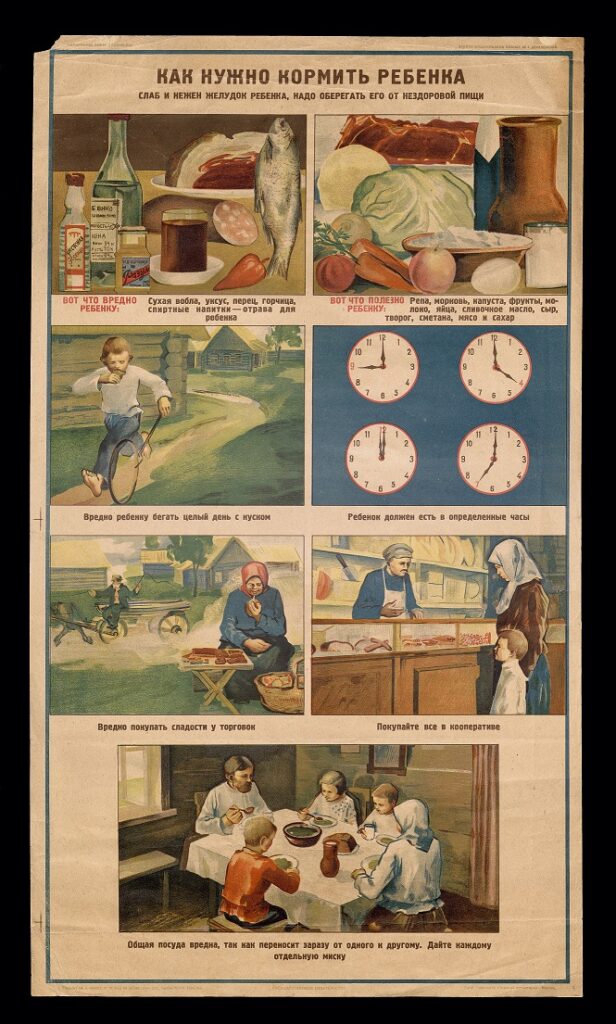

Most of the materials in this collection cover four different major goals of the Soviet state during this time: collectivization, atheism, anti-alcoholism, and child-rearing, all of which tie into the overall goal of developing a productive socialist state.

Starting in 1928, Joseph Stalin began implementing a series of five-year plans, of which the goal was to further economic growth and development through new programming and reaching certain quotas. The first of these plans was centered on collectivizing agriculture, basically modernizing Soviet agriculture through collective farming while also developing agricultural technology and methods. To spur on this movement much of the propaganda from this time resembles that of war time propaganda, urging citizens to the “battlefield” of the collective farm.

Concerning religion, the Soviets believed it to be a serious obstacle to achieving a highly developed socialist society. With this view, religion was considered an irrational absurdity throughout most of the 20th century, religious property was seized or destroyed, atheism was pushed in schools, and many posters were created to stress this message.

The problem of alcoholism was also something taken seriously by the Soviet Union, on and off throughout the 20th century. Like religiosity, alcoholism was seen as a barrier to Soviet society, especially when alcoholics were unable to work and support the Soviet machine. As a result, alcoholism needed to be pushed against, and posters such as the ones in this collection advertised it as an evil needing to be eradicated.

Another main propaganda topic during the early 20th century was childhood health, development, and schooling. Children were revered as the future members of the Soviet socialist future, so it was incredibly important to raise them to be healthy, well-treated, and well-educated. Propaganda worked to show the importance of keeping a child healthy and well-fed, and to recommend kindergarten programs.

Posters such as these weren’t meant to stick around forever. They would be swapped out with the next wave of propaganda or simply lost due to daily wear and tear. With this incredibly ephemeral nature it’s really cool we have this unique little bit of history at our library, especially as Russian and Soviet history is not an area often collected in by major institutions.

This collection of posters is fully digitized and available to view.

Leave a Reply