If a company publishes school dictionaries, it probably wants students and teachers to use their dictionaries effectively, so it comes as no surprise that companies used to arrange for publication of classroom and homework supplements to improve the value of those dictionaries, the principal products. Clarence L. Barnhart, who edited many dictionaries for major commercial publishers (the Lilly Library is also home to the Barnhart Collection), pointed out that commercial monolingual English dictionaries are “out of necessity […] of a popular nature because they must depend on widespread acceptance by the general public.” What better way to build an audience for dictionaries than to introduce them in the schools? Pedagogical support for dictionaries inevitably overlapped with marketing.

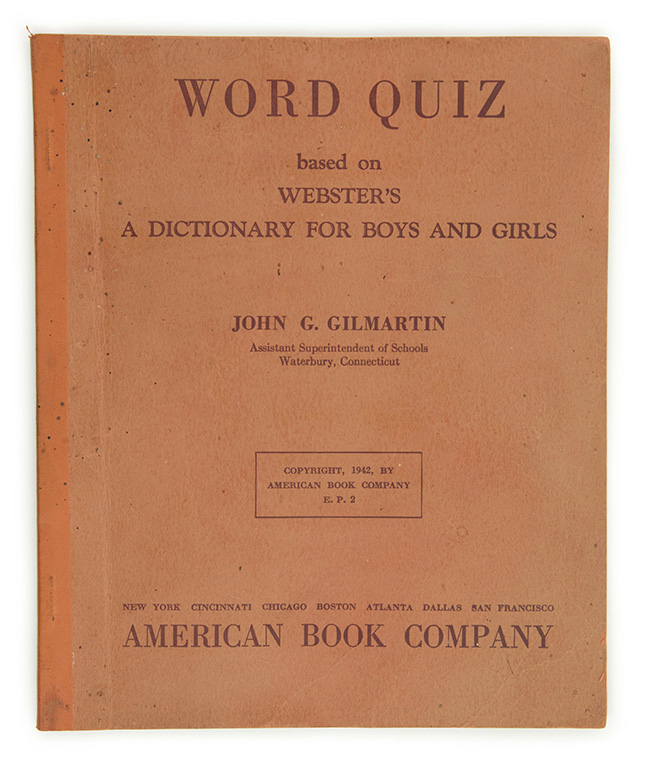

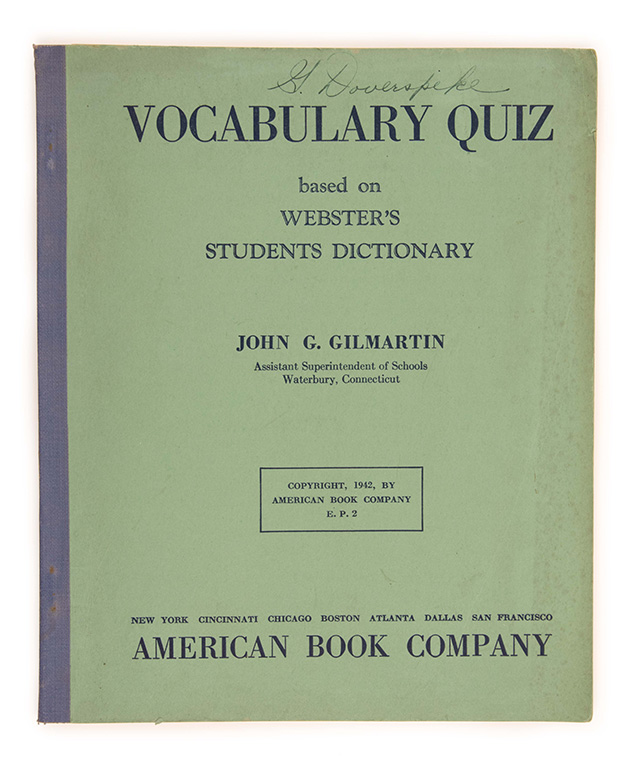

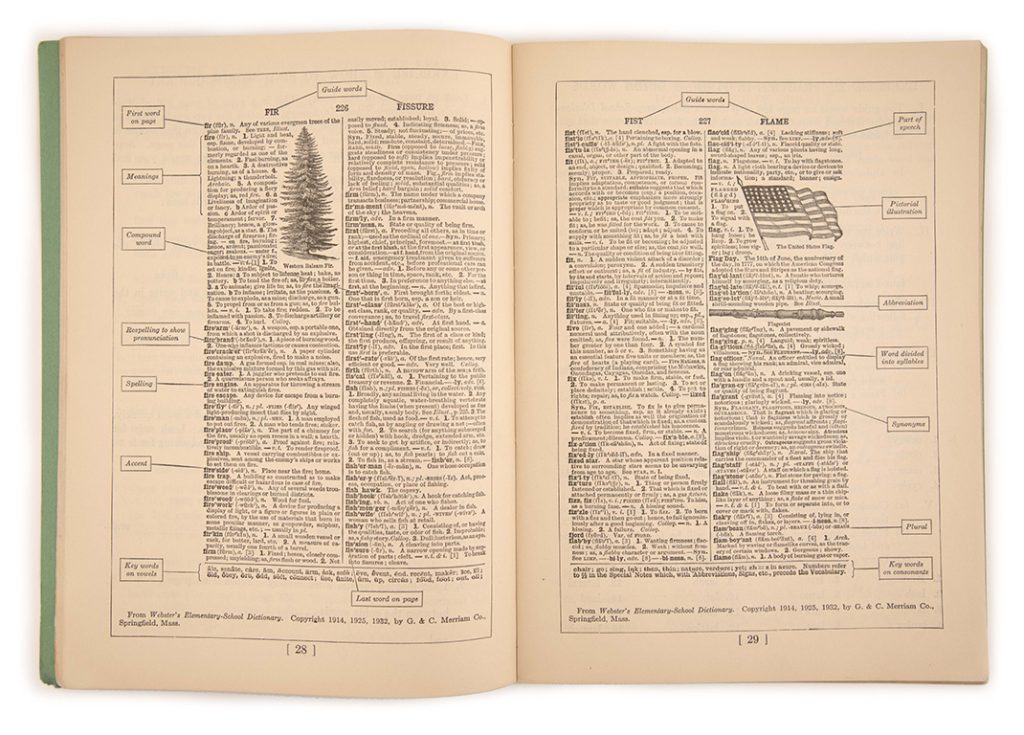

During the early 1940s, John G. Gilmartin, Assistant Superintendent of Schools in Waterbury, Connecticut, prepared educational supplements for Merriam-Webster school dictionaries, and the Kripke Collection includes examples of his work. He supplied a Vocabulary Quiz based on Webster’s Students Dictionary (1942) at 40 pages, 8-page answer pamphlet inserted; a Word Quiz based on Webster’s A Dictionary for Boys and Girls (1942), at 32 pages, which probably also had an answer pamphlet, though we haven’t yet found it in the Kripke Collection; and a Handbook for Webster’s Students Dictionary (1944), another 40-pager with an 8-page answer pamphlet.

These are all unprepossessing, functional books published by the American Book Company, built to survive use by rambunctious elementary and junior high school students. The first has green covers with blue binding tape (the booklets are stapled), the second was wrapped in bold orange, rather faded now, while Madeline’s copy of the last, in blue covers, belonged to Geraldine Doverspike, presumably a teacher: She inscribed the inside front cover with “Personal Property of …” presumably because she worked in a place of mostly public property. She notes, too, that it was a “Sample Copy received Nov. 5, 1945.” She was punctilious about such things, but the book is blank: Ms. Doverspike did not complete the exercises herself. Perhaps she never assigned them to students, either, despite her copy of the answer booklet.

All the dictionary workbooks assume, wisely, that students learn by doing, and that having them do something regularly with their dictionaries — exercises — would reveal more about the value of dictionaries than would leaving them tidily on a book truck in a corner of the classroom.

Attention to dictionaries in American classrooms has all but evaporated. Some will look at booklets like these and imagine a Golden Age of school dictionaries, while others will see the whole enterprise as implausible, even utopian — why in the world would dictionary publishers think that students would appreciate dictionaries more because they required homework? How likely is it that schools, parents, and students would enthusiastically expand the R’s from Readin’, Ritin’, and Rithmatic to include Reference?

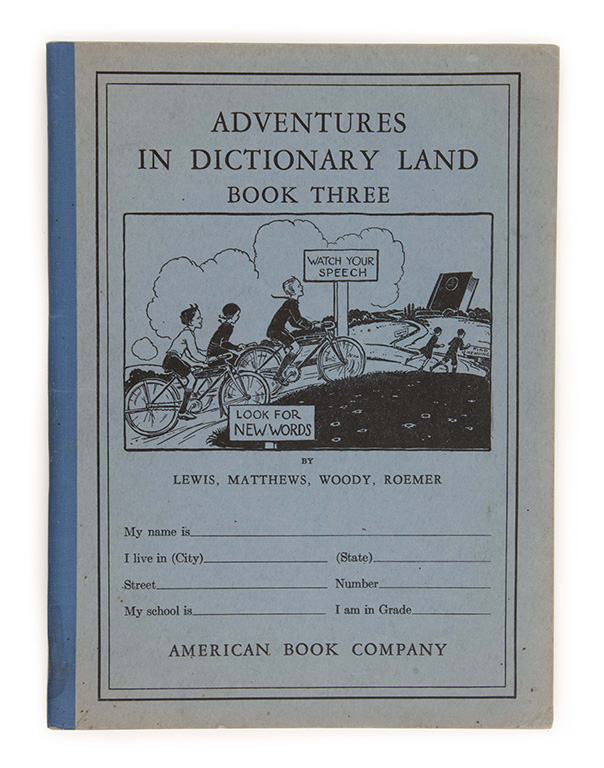

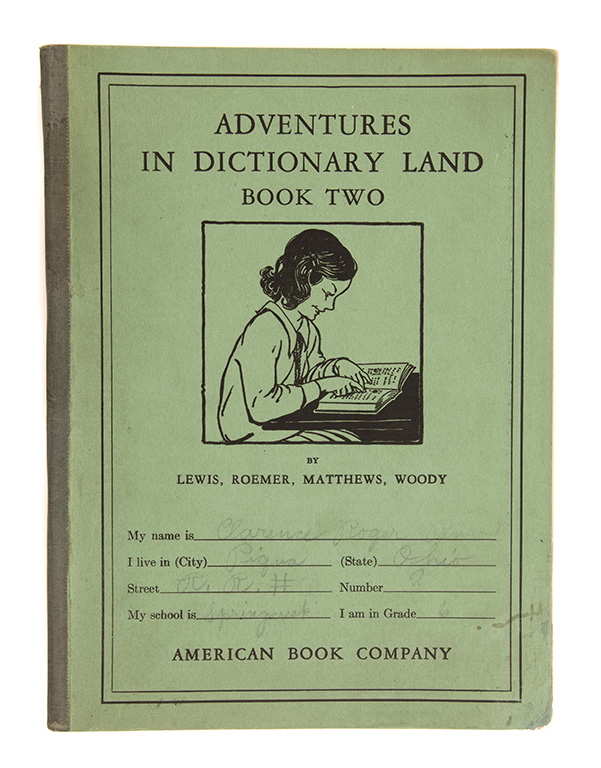

An earlier series of dictionary guides for schoolkids indulged the fantasy. A team of experts — E. E. Lewis (Ohio State University), W. L. Matthews (Western Kentucky State Teachers College), Clifford Woody (University of Michigan), and Joseph Roemer (George Peabody College for Teachers) — compiled Adventures in Dictionary Land for Use with Webster’s Dictionary for Boys and Girls (1932, by the American Book Company), a series of three booklets. Madeline collected two differently bound copies of Book 3 and one of Book 2 — we haven’t found a copy of Book 1 … yet. The cartoon covers of these booklets show kids walking and bicycling into a place called Dictionary Land.

But Adventures in Dictionary Land aren’t merely hopeful works, nor even merely ancillary texts that promote the dictionaries they serve, nor even, perhaps, merely make-work for beleaguered public-school students. Madeline collected a copy of Book 2 filled in by Clarence Roger Somebody — the penciled surname has faded to illegibility over time — of Piqua, southwestern Ohio, where he attended sixth grade at Springcreek Elementary School. In Clarence’s copy of the workbook, Madeline collected proof of concept for the whole auxiliary workbook pedagogical and promotional scheme. All 80 pages are complete, and Clarence was clearly an attentive student, as all the answers are correct.

I found “Exercise 29. Finding Emblems, Signs, and Symbols” one of the more interesting sections. Here’s the set up: “Your dictionary gives many emblems, signs, and symbols which will aid you in your school work. See how many of the signs and symbols called for in this exercise you can find in your dictionary and copy in the spaces below.” As item 1, the authors provide a sample, “The sign for the dollar mark __$__.” Item two asks that the student copy the symbols for pounds sterling, per cent, accent, hyphen, (French) franc, and an interrogation mark.

A good start, but it gets even more interesting. Boxes are then provided for copies of the following figures: “3. Hieroglyphics,” “4. Swastika [in 1932!],” “5. Flag [Clarence’s was identifiably American],” “6. G clef,” “7. Hourglass,” and item 8 calls for a series of crosses, Latin, Greek, Maltese, and St. Andrew’s. Item 9 asks students to “Find and draw three additional symbols here,” and Clarence chose +, -, and ÷.

Dictionaries are about words first, of course, but many have included encyclopedic material, and symbols figure somewhere between the two modes. While the exercises are about the symbols and learning to find things in dictionaries, they also introduce vocabulary, some of which was likely unfamiliar to Clarence and his sixth-grade classmates in Piqua (hieroglyphics, franc, St. Andrew’s cross). We may assume that Language Arts (as we call it now) was home to the dictionary, but the cross-curricular value of word knowledge, which is also world knowledge, comes across in the exercises. Why don’t we use dictionaries similarly in schools today?

These notebooks reveal flesh-and-blood people thinking about dictionaries. It’s not all pie in the sky. Geraldine Doverspike probably taught the material; Clarence Whatever-his- name-was diligently devoted hours of his afterschool play time to answering questions about words with reference to a dictionary. They didn’t visit Dictionary Land. They lived in the real world, where dictionaries mattered, nonetheless.

Leave a Reply