Two spools of thread in a box. A pen that looked like it had been chewed on. A plexiglass lamp. Which, if any of these, were avant-garde poems? This was the puzzle that faced me when processing Solt mss. II, the 59-box collection of concrete poet and scholar Mary Ellen Solt. Concrete poetry is a visual form of poetry in which the layout and typography of the poem contribute to the meaning as much as any linguistic content; my favorite of Solt’s poems, “Moonshot Sonnet,” has no linguistic content at all. (See Reference Librarian Isabel Planton’s blog post for more about Solt’s career and her best known poem, “Forsythia.”) Concrete poetry is just experimental enough that, when processing the collection, I didn’t want to rule out the possibility that the nibbled-on pen was actually an unorthodox poem symbolizing the difficulty of writing, or something. I called this game “Poem or No-em.”

The bulk of my job as an archivist is processing archival collections. The Society of American Archivists defines processing simply: “preparing archival materials for use.” When new collections arrive at the library, the boxes are often chaotic and the materials inside them are in no obvious order. It is difficult for researchers to use these materials (or even know what materials exist!) when the contents of each box are a mystery. My job is to figure out what is in each of the 59 boxes and to sort the materials into categories (called “series” and “subseries”) so that researchers can find what they are looking for more easily.

But Mary Ellen Solt was someone who resisted easy categorization. In a single folder, I would find unlabeled drafts of her own poetry from three different decades, a letter or two from “Bill” (that is, major twentieth-century poet William Carlos Williams), alongside the booklet that came from her mattress—and this folder would be labeled “recipes.” Part of archival processing is forcing things—sometimes unnaturally—into neat categories for the practical reason that scholars who wish to study William Carlos Williams’ letters cannot easily find them if they are scattered throughout 60 different boxes in various folders labeled “recipes.”

So how does an archivist make decisions when processing? How did I decide what was a poem (which I sorted into a subseries called “Poetry”) and what was a no-em (which I sorted into the series “Personal”)?

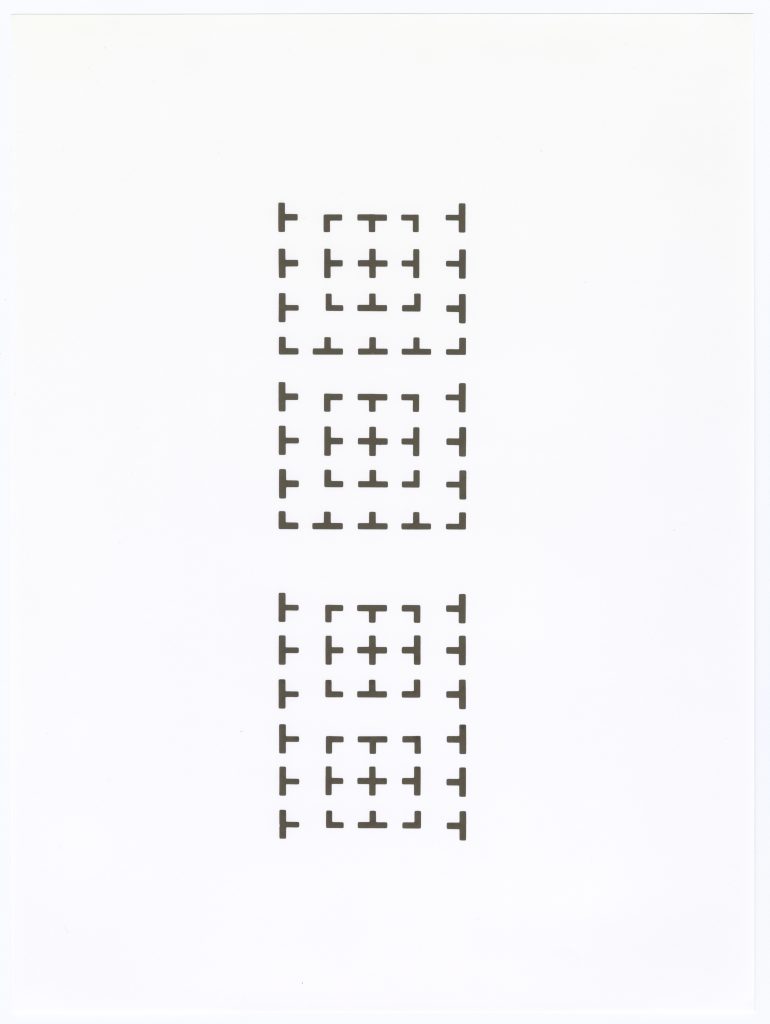

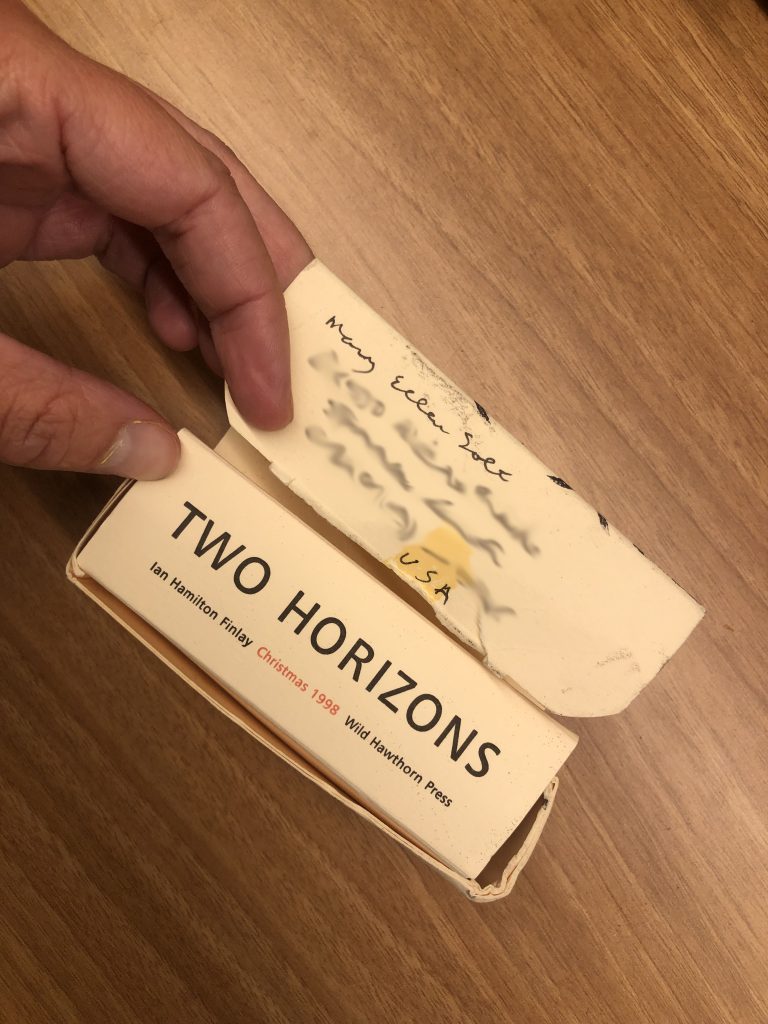

First, research. My first step in working on any new collection is to research the creator, her friends and colleagues, and her area of expertise. For example, basic biographical research revealed that Solt developed an interest in concrete poetry partly through a formative friendship in the 1960s with the Scottish poet Ian Hamilton Finlay, and her first concrete poem to be published appeared in Finlay’s Poor. Old. Tired. Horse (P.O.T.H.). Basic biographical research on Finlay reveals that he is known both for concrete poetry and for object poems, most notably his sculptural and landscape-based poems in his gardens at Little Sparta. Two spools of thread in a box may or may not be a poem, but two spools of thread in a box with Ian Hamilton Finlay’s name on it? Definitely a poem.

Ian Hamilton Finlay is a Scottish poet known for his concrete poetry and object poems. The presence of Finlay’s name and a title on the box suggests that these spools of thread are intended to be a poem.

Second, I make arrangement decisions based on familiarity with the collection and the creator. After Finlay’s spools of thread, I had been primed to view any object in the collection as potentially a poem. But arrangement is an iterative process: I spend months with these collections, and I get to know intimately the creator’s personality and way of thinking (which I try to preserve in my arrangement as much as possible). Aside from “The Peoplemover,” a kind of performance art piece that found Solt at her most experimental, I came to understand that Solt’s own poems tend to be fairly traditional: they tend to contain words or at least symbols and to be printed on paper. She is not one to grab household objects and call them poems. And Ian Hamilton Finlay loves to put his name on his work: when he grabs household objects and calls them poems, he will at least label them. Therefore, the nibbled-on pen was probably not an avant-garde poem about the difficulty of the artistic process, but just a nibbled-on pen. I deaccessioned it.

Third, I decide poem or no-em based on context clues within the collection itself. Unlike the pen, the plexiglass lamp had obviously been created intentionally, and moreover had already been jokingly described to me by a colleague as “the Solt poetry lamp.” “Poetry lamp” is such a good turn of phrase that I really wanted to call it a poem, but a note from Solt’s daughter complicated this categorization: “This is the plexiglass sculpture my mother made in 3-D design that was mentioned twice during the memorial.” We could quibble about where the line is between sculpture and poetry, but it seemed from this note that Solt’s daughter and possibly Solt herself did not consider the lamp to be a concrete poem. I could find no evidence that she ever wrote about it or exhibited it as such. I chose to put the lamp in the subseries with materials from Solt’s memorial service so that the lamp was grouped with the materials that provided context for its creation. This is perhaps not the most intuitive categorization—which is why those doing archival research should make a habit of looking through an entire finding aid and not just where they expect to find what they are looking for. Arrangement is often based on the idiosyncrasies of both the creator and the archivist.

Though a colleague had jokingly described this item to me as a “poetry lamp,” a note from Solt’s daughter suggests that it is actually a sculpture Solt made in a 3D design class. We could quibble about where the line is between sculpture and poetry, but I found no evidence that Solt herself considered it to be a poem.

It seems like a straightforward, uncomplicated prospect to “prepare archival materials for use” by putting things where researchers can find them—simply sort the William Carlos Williams letters with the William Carlos Williams letters and the poetry with the poetry. However, while it’s maybe self-evident what a William Carlos Williams letter is, it is not at all self-evident what a poem is—especially when dealing with concrete poets who deliberately pushed the boundaries of what poetry could be. For the purposes of processing the collection, I seem to have landed on the definition that a poem is anything the creator intended to be a poem, which is why Finlay’s spools of thread are a poem and Solt’s lamp is not. This is not the definition I would propose if I were a scholar pondering upon a universal theory of poetry, but it is a definition I had to embrace with the ruthless pragmatism of an archivist whose job it is to physically sort materials and put them in boxes. You may disagree with my categorization, but at least these items are no longer in folders labeled “recipes.”

Leave a Reply