Early dictionaries were books for readers. Lacking the tools of twenty-first century marketing, early dictionary publishers advertised a forthcoming dictionary with a prospectus, sometimes a brief introductory essay by the dictionary’s editor, sometimes with a synopsis of the dictionary’s key features. For dictionary readers, such a prospectus was big news. Madeline Kripke’s collection includes lots of promotional material for dictionaries. I recently encountered two prime examples of the prospectus approach.

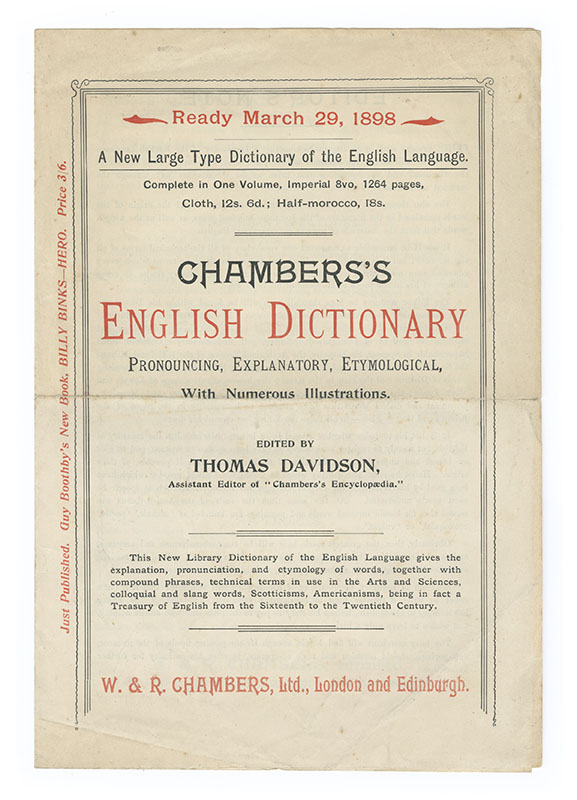

One is a four-page announcement of the impending Chambers’s English Dictionary, which would be “Ready March 29, 1898,” edited by Thomas Davidson (1856–1923), who had been assistant editor of the Chambers Encyclopedia. The front page informs us that the dictionary is “A New Large Type Dictionary of the English Language” — the capitals indicate emphatic marketing — and the dictionary is “Complete in One Volume, Imperial 8vo, 1264 pages, Cloth, 12s 6d; Half-Morocco, 18s.” It was a fairly grand dictionary — in terms of pages, about half the size of Webster’s Third (see a previous post). But the description signifies more than that: you can have a fairly grand dictionary bound in cloth, but you can have a grander grand dictionary if you pay half the cost again of the ordinary dictionary for special binding. Social class is written right into the marketing.

The back page is a specimen page, running from moral theology to morne “the blunt head of a jousting lance.” But those two entries leave the wrong impression. The intervening words are more commonplace. In what book does one encounter morne in this sense? Suffice it to say, it’s not in the official Scrabble dictionary. The OED answers our question: Sir Philip Sidney’s romance Arcadia, which few now read, among other quotations from texts no one reads. One won’t find the word in Charles Richardson’s New Dictionary of the English Language (1836 /1837) or John Ogilvie’s The Imperial Dictionary of the English Language (1847/1850). How many Victorians tilted with lances with rebated heads? It’s so medieval.

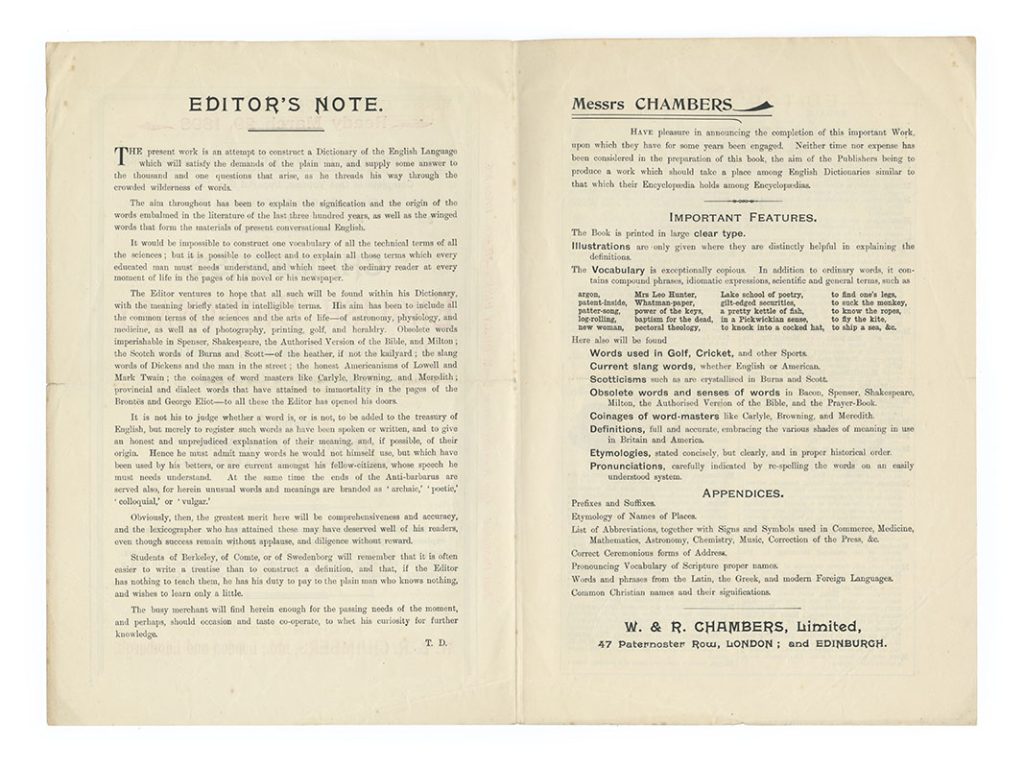

Inside, the third page runs through the dictionary’s features. We’re told that one will find there “Words used in Golf, Cricket, and other Sports” [bold face indicates emphatic marketing]; “Current slang words, whether English or [gasp!] American”; Scotticisms such as are crystallised in Burns and Scott [Chambers was first and foremost an Edinburgh publisher]; Obsolete words and sense of words in Bacon, Spenser, Shakespeare, Milton, the Authorized Version of the Bible, and the Prayer-Book”; Coinages of Word-Masters like Carlyle, Browning, and Meredith; Definitions, full and accurate, embracing the various shades of meaning in use in Britain and America” [one senses that America is part of this dictionary’s market]; Etymologies, stated concisely, but clearly and in proper historical order; and Pronunciations, carefully indicated by re-spelling the words on an easily understood system.” That covers all the bases (an idiom from an “other sport”) important to most dictionary users.

Page 2 is a brief essay by the editor, from which I cull two especially resonant quotations: (1) “It is not [the editor’s role] to judge whether a word is, or is not, to be added to the treasury of English, but merely to register such words as have been spoken or written,” a lexicographical sentiment very much in line with James Murray’s account of a dictionary’s responsibilities in his preface to the OED; and (2) “Obviously, then, the greatest merit here will be comprehensiveness and accuracy, and the lexicographer who has attained these may have deserved well of his readers, even though success remain without applause, and diligence without reward.” Truer words than this lexicographer’s lament were never spoken; that passage alone makes the prospectus a valuable document.

Chambers is a serious publisher of dictionaries, most lately of Green’s Dictionary of Slang (2010), but dictionaries by themselves rarely pay the bills — leave that to fiction. My favorite part of the prospectus for the Chambers’s English Dictionary doesn’t run across the page but rather up the left edge: “Just Published. Guy Boothby’s New Book, BILLY BINKS — Hero. Price 3/6” [yet more emphatic marketing]. You won’t accumulate all your profit in the lexicographical basket, so why not use margins of the prospectus to reach a broader audience?

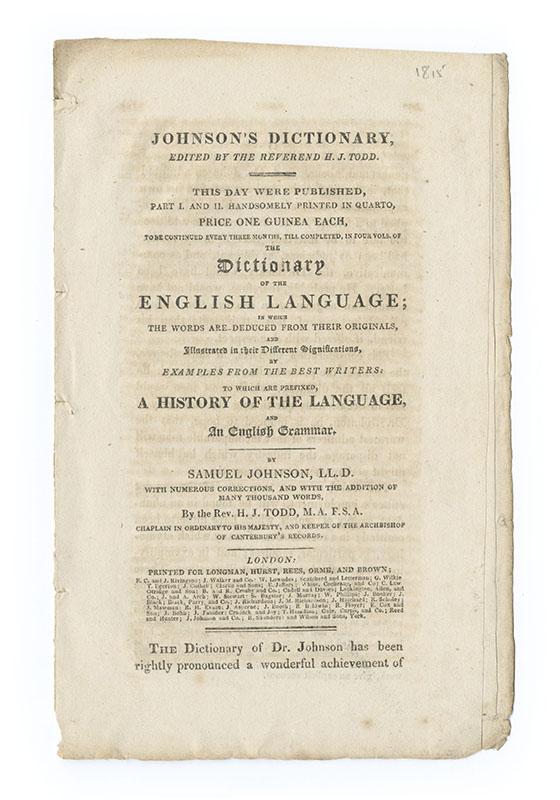

The second example is both earlier and rarer, a prospectus for the Reverend Henry Todd’s revision (1818) of Samuel Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language (1755). The prospectus ends with the date on which Todd wrote the text, August 1, 1814, but someone — possessed of bibliographical knowledge, one hopes — has penciled onto the right front corner “1815.” The text is a straightforward essay about the greatness of Johnson’s work and why it was no longer as great as it was in 1755 or shortly thereafter — Todd’s labors turned a two-volume into a four-volume work.

Todd (1763–1845) had edited the works of Milton and Spenser and served as Librarian at Lambeth Palace, London home of the Archbishop of Canterbury. He carried enough literary and cultural authority for his criticism and improvement of Johnson’s dictionary to matter. He announced the new edition modestly, however: “After all, what the present editor has done, he considers but as dust in the balance, when weighed against the work of Dr. Johnson.”

Even among the literati, expectations for effective marketing have changed considerably since the beginning of the nineteenth century. I flip through the pages of the TLS and the New York Review of Books to register new books on offer from publishers far and wide. Would I have had the patience to read the eight pages of Todd’s prospectus? Probably, because books were relatively so much more expensive then. Todd’s dictionary sold for a guinea, or twenty-one shillings, roughly $2200 for the four-volume set in current US dollars. It wasn’t a casual purchase at the booksellers but an investment.

Todd’s prospectus must have been an investment for Madeline, too, though I have yet to find a record of what she paid for it — in book-world lingo it’s a Fine copy. I found it enclosed, not in one or two but three plastic sleeves.

Leave a Reply