Madeline Kripke was born in 1943, so she lived through the rise of teen culture and teen-directed marketing in real time. We’ve already noted the copies of the Dobie Gillis Dictionary (1962) and Steve Allen’s Bop Fables (1955) that Madeline collected as celebrations of American teens and hipsters ascending. When she collected them, long after she lived through the cultural change they represent, she saw them in context and took them seriously, not as foam on the top of more serious cultural matters. After we discovered Allen’s book, we came across a recording of Allen reading the fables, which Madeline had witnessed or collected. We haven’t listened yet, however — they’re recorded on a minicassette, and who has a minicassette player handy in 2022?

When Madeline was about sixteen-years old, an outfit in New Jersey, called Standard Products, decided to make some money in the teen market for dictionaries. The company’s name wasn’t Premium Products, so when Standard Products published Webster’s Dictionary, it not only traded on the famous dictionary name but produced a generic product at the least possible expense — good business but disappointing lexicography. We’re lucky that Madeline collected this invitation for teen girls to accessorize with dictionaries.

The text was prepared by Edward N. Teall, a Princeton alum who spent a career in newspaper, magazine, and book editing and who wrote books and compiled dictionaries on the side. Among his books is the irresistible Meet Mr. Hyphen (and Put Him in His Place) (1937), and, as a proofreader for Webster’s Second New International Dictionary (1934), he had a certain lexicographical cachet about him. He’s not responsible for Standard Products’ Webster’s Dictionary, because he’d been dead for twelve years before it was released. He is listed on the title page, however, because he was responsible for the Modern New Handy Pocket Dictionary (1939) and later iterations of the same for Books, Inc., yet another dictionary publisher of no repute, from which Standard Products either bought or licensed the product of the late Mr. Teall’s labor. The title page carries a cautious caveat: “This dictionary is not published by the original publishers of Webster’s Dictionary, or by their successors,” that is, Merriam-Webster, Inc., which had employed Teall in the production of Webster’s Second.

This bit of book history explains why Standard Products’ Webster’s Dictionary was not up to date in 1959. The title page might lead one to believe something different: this is, we are told, the “Concise Edition — Containing the essential words in current demand in School, Office, and Home — with new automatic pronouncing key and simplified definitions of scientific, technological, and general popular terms.” Despite the nuclear revolution and the threat of nuclear war in 1959, nuclear and fusion aren’t entered in the dictionary at all, and fission is defined as a process of splitting anything, without reference to atoms. One shouldn’t expect too much from a dictionary of 378 pages, and this one includes lots of encyclopedic information, too, like the text of the United States Constitution, to which, admittedly, every teenager ought to have easy access. Sure, Standard Products could have paid someone to update the wordlist and definitions, but why pay someone to reinvent the wheel? Anyway, Standard Products literally wasn’t in the business of providing its dictionary’s users with a premium dictionary experience.

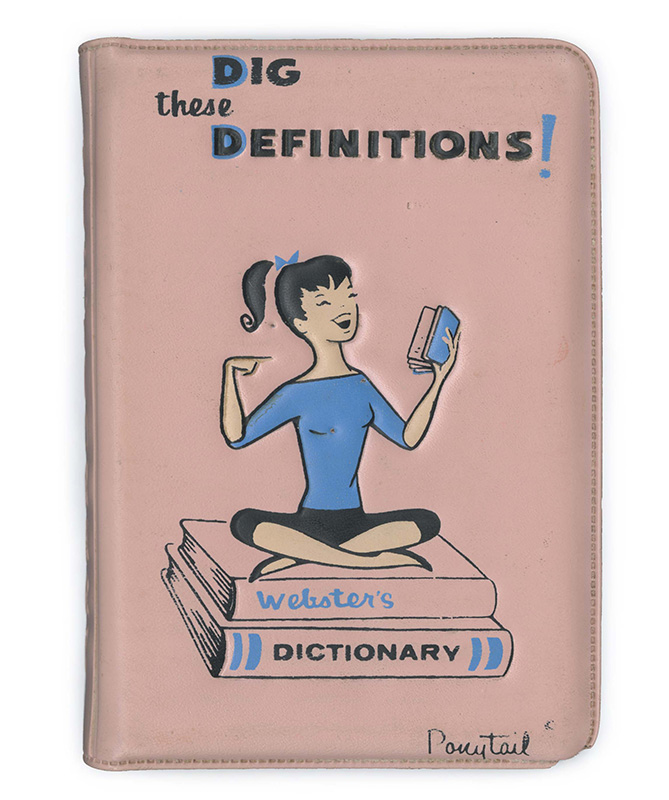

Rather than emphasizing the dictionary’s text, Standard Products emphasized the book’s cover, and surely the cover convinced Madeline to add this otherwise shabby Webster’s Dictionary to her collection. It’s puffy pink plastic, like an infant’s book — you could chew on it. A teen girl with a ponytail tied in a blue bow sits on two large volumes, spines towards the viewer, the top one titled Webster’s and the bottom one titled Dictionary. The girl holds a little book in her left hand – one might call it a new handy pocket dictionary especially for teens – points at it with her right hand and laughs with joy, just as every reader of a dictionary should.

The ponytail is a big thing, so inescapably “then,” that someone inked Ponytail in black on the front cover’s bottom right corner. To reassure anyone confused by the decoration, DICTIONARY is cut into the thick plastic spine. The three-dimensional aspect of the cover reminds us that dictionaries are material objects. They aren’t only about words. They’re also about selling the social status implied by ownership of certain types of dictionaries. In 1959, your aunt could present you with a calf-bound copy of Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary upon your high school graduation because you were that sort of girl. Or, she could see you as another sort of girl, one who deserved a fun, plastic dictionary. Standard Products banked on making a basic dictionary cool rather than edifying, just by means of plastic and color and the fanciful mirroring of real-life teen dictionary use in the cover image.

Across the top of the cover, in blue and black letters, runs the best line of all: “Dig These Definitions!” Language like dig belongs to the time and it qualifies as a “general popular term,” but if you look dig up in Teall’s 1930s dictionary, you’ll learn that it means what you do with dirt and a spade, not what hipsters like Maynard Krebs, of Dobie Gillis fame, meant by it. (Actually, dig in the hip sense ‘appreciate,’ as in “Can you dig it?” or on the Webster’s Dictionary cover, was a 1930s word, but Teall, like many a lexicographer, was already behind the times.)

Standard Products wasn’t wrong about its dictionary’s appeal to some elements of the teen market. Madeline’s copy once belonged to a certain Barbara Marlow, who lived at 2518 W. Queen, somewhere in the United States in 1959 — so far, no luck in tracing Ms. Marlow further. Either she judged the book by its cover, and it satisfied her sense of what dictionary best represented her, or someone among her family and friends saw her represented in it, whether as a compliment or a caricature, we’ll never know.

Leave a Reply