In my last post about Wes Anderson’s debut short “Bottle Rocket” I introduced the themes of simplicity and nostalgia and talked about the literary quality of Anderson’s screen writing. This time around I’ll be moving into his second feature film “Rushmore” and attempting to explore these same themes and how they undergo transformation with Anderson tackling a bigger cast of characters focusing on a very different but similarly self-involved protagonist.

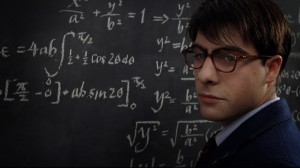

The film opens with a dream that idealizes the protagonist. The scene revolves around the protagonist solving the hardest geometry problem ever, gaining him the recognition and acceptance of all of his peers. Achieving/existing in this idealized world and the recognition that comes with it turns out to be the protagonist’s goal for the entire piece. As we progress through the plot we see Max Fisher engaging with his peers and one of his school’s teachers who he spends the majority of the film trying to woo. It is apparent from the very start that Max considers himself a lot older than he is. This is his central delusion and contributes to his hubris and his eventual fall from grace (not to spoil the film or anything, but what is a character without conflict?)

The conflict of the movie is simple: a boy trying to grow up too quickly learns what it means to “meet yourself where you are.”

This is seen through all of Max’s relationships within the film. His relationship to the elementary school teacher, Rosemary Cross, for example is him trying to act the part of a grown man when he’s really only a boy. He tries to solve the problems of adults with the knowledge of a child and he ends up failing. We see this idea again with Max’s relationship to the school where he assumes that by being extremely involved he has gained a power that he actually does not possess over the administration of the school so that later when it comes to dealing with his own fate at Rushmore when it comes into question in the middle of the film (after Max has failed all his classes), he is left floundering, heart-broken, and expelled. Again he attempts to meet adults as their equals and is promptly knocked back down and made to come to terms with his status as student (or really more like child.)

But, I think, as glum and uninspiring as this sounds, the movie’s focus on the acceptance of these things is a positive message that reads more towards the side of being happy with being a really talented kid than it does towards being upset that you don’t have the power/status of an adult.

Anderson also uses the relationship that Max attempts to have with Rosemary Cross to mirror his feelings towards this nostalgic setting. Pitting the almost hostile love that Max feels towards Rushmore as his career there is put in jeopardy and is eventually snubbed with the pressure he feels to take revenge on Herman Blume after he “steals” Mrs. Cross from him.

The focus Anderson takes on Max’s delusions of grandeur are very similar thematically to the delusions of Dignan in “Bottle Rocket,” though Max’s are more fully realized.

We are made to be more sympathetic towards Max and the way he is trying to impress us. (A very similar type of impressing goes on concurrently between Max and Mrs. Cross as he attempts to seduce her.) This feeling of sympathy which we lacked a little in “Bottle Rocket” could be because unlike in the short, we end up feeling like we know Max a lot better just from spending more time with him and with Anderson’s funny kind of exposition, or it could just be because in this film we find Anderson exploring a kind of emotional crisis we can all identify with more generally. I think it’s a little bit of both.

Stylistically this film is done in five acts like a traditional play and comes off as almost a kind of moving picture book. This way of presenting the film lends to its overall nostalgia and helps us as an audience see into Max’s life and enter his consciousness a bit more thoroughly than the short. It is also a simplification of traditional film making through the use of traditional play structure.

The play structure in itself is almost too simple, giving the story an absolute couture moving easily through exposition, rising action, crisis, conflict and resolution. This simplification of the story arc gives the theme of trying to exist outside of the constraints of something as out of one’s control as age more of a push. further though it might give us a peak into Anderson’s personality as an artist and his feelings towards the craft of filming. To elaborate: Anderson’s protagonist is struggling against being too young to be taken seriously, right? Well it is possible that Anderson himself was dealing with similar issues being a very young film maker at the time and this being only his sophomore effort as a director. This is all conjecture, of course, but it’s something to consider when trying to understand the motivation behind the themes of this and all his other films, especially when considering them as literature.

Of course on a more concrete level, in what is being established with this film as Anderson’s style, the film is shot in very simple and usually pretty wide angles giving it’s setting at a very old-feeling prep school (reminiscent of the setting of John Knowles’s “The Separate Peace” or Salinger’s “Catcher in the Rye” both novels that are nostalgic for youth and illuminate the sheltering nature of the prep school) this kind of sprawling feel but also lending it an air of Anderson’s trademark whimsy with his quick camera cuts and panning shots. The combination of crisis of ego in his characters and colorful fun in his cinematography comes together beautifully here launching Anderson solidly into what will become an extremely popular and prolific career.

Overall the film fits nicely into Anderson’s progression as an artist by giving him space to create outside of his break-out feature and helping him to develop his style as a director and his voice as a screenwriter in new material, and furthering our knowledge of his authorial personality and obsessions into the next film to be looked at in this series, “The Royal Tenenbaums.”

Leave a Reply