When it comes to mainland Chinese cinema, many in the United States are familiar with wuxia (martial arts) films such as House of Flying Daggers. Some may be fans of “scar films” that emerged from the extreme hardships of the Cultural Revolution. I myself was introduced to Chinese cinema through 90s classics such as Raise the Red Lantern and Farewell My Concubine. What these all have in common is that they were made by filmmakers in the “Fifth Generation” or before.

Leslie Cheung in Farewell My Concubine (1993) by Chen Kaige

Leslie Cheung in Farewell My Concubine (1993) by Chen Kaige

The Fifth Generation filmmakers–such as Zhang Yimou, Chen Kaige, Tian Zhuangzhuang–comprise a group of Beijing Film School graduates who began working around the mid 1980s. After graduating, many of them were recruited by the Xi’an Film Studio where they went on to make a number of aesthetically and commercially successful films like the ones mentioned above. The term “Fifth Generation” is thought by many to be an umbrella term that is more descriptive of a time period than of a collective style or subject. However, as they were the first filmmakers to work after the period of absolute government control, they are united in their divergence from the socialist-realist style and ideological adherence of Cultural Revolution Cinema.

Gong Li in Raise the Red Lantern (1991) by Zhang Yimou

Gong Li in Raise the Red Lantern (1991) by Zhang Yimou

While most of these directors are still active today (Zhang Yimou’s largest-budget film The Great Wall was released in 2016), there has for some time been a Sixth Generation of Chinese filmmakers who have made their own way. After the protests and massacre at Tiananmen Square in 1989, the government censorship and the lack of funding forced many aspiring filmmakers underground. Some of these films, such as Golden Lion winner Still Life by Jia Zhangke, are made with non-professional actors. Others are shot with low quality equipment with budgets less than $10,000. The films by Sixth Generation filmmakers are more interested in contemporary industrialization and loneliness, and are far less lush and romantic than their Fifth Generation counterparts.

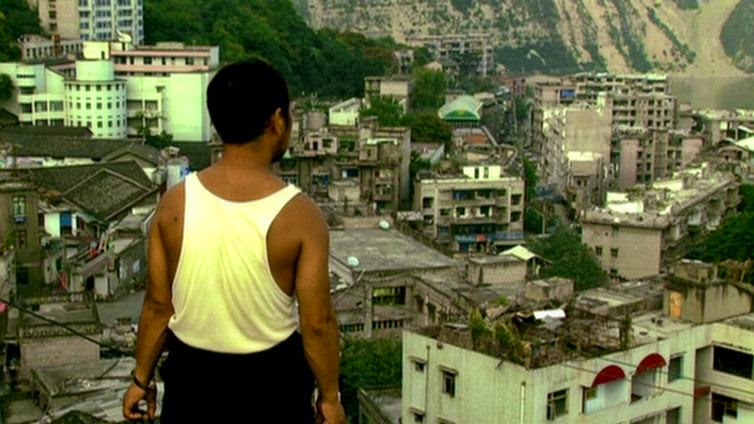

Han Sanming in Still Life (2006) by Jia Zhangke

Han Sanming in Still Life (2006) by Jia Zhangke

In addition to Jia Zhangke, there is Wang Xiaoshuai, Zhang Yuan, and Lou Ye. Anyone who is a fan of the florid and expressive films like Ju Dou or Hero might at first find films like Still Life or The Days cold and gritty, but there is an urgency to them that is very compelling.

Since the early 2000s, there has been a “dGeneration” of filmmakers, with “d” standing for digital. Most of these have been screened on the independent circuit. Some well-known titles are Taking Father Home by Ying Ling and Oxhide by Jian Yi.

If this seems like a lot to you, it’s because it is. And these are just the mainland Chinese films from the past 30 years or so. If we broaden the scope past the People’s Republic of China to include filmmakers from Taiwan (Hou Hsiao-Hsien, Edward Yang), Hong Kong (Wong Kar Wai, Ann Hui), and diasporic filmmakers like Ang Lee, the list grows exponentially.

We have many of these titles here at Media Services. Come check one out! AL

Anni Liu is a graduate student in Creative Writing at IU and a published poet and essayist.

Leave a Reply