This post is part of a series of reflections from the “Midwest Indigenous Cartography” project, which is an ongoing initiative that seeks to explore Indigenous worldviews, conceptions of cartography, and map-making practices, particularly in the Midwest.

I struggled for years to identify as Native for many reasons. So, when I took a philosophy class on personal identity, I jumped at the chance to write my term paper on Indigenous personal identity. As I learned doing research in an attempt to write this paper, however, I was applying a white concept to native culture. My research showed that Native personal identity does not really matter as much as the relational identities we form through our bonds with each other.

“How it Is” by Viola Cordova shows this clearly. Early in her book, she talks about how in her first philosophy class, she was ridiculed by her professor when she used “we” instead of “I.” She felt shocked that someone would say “I” because her beliefs were not just her own but were of her nation.

Relational identity is also seen in “The Wind is My Mother” by Bear Heart, an autobiography intended to encourage us to utilize traditional tribal medicine to maintain our culture and spirituality. Bear Heart is a medicine man; however, that is an identity we have placed upon him. Medicine men cannot identify as medicine men themselves; those they heal give them that title. Their identity in that way is wholly relational. The reasoning is it’s not their knowledge, it’s the creators they merely translate it. The study of Indian Medicine is something that takes a lifetime of continued dedication.

When I came onto this project, I had read both books in a different context. However, I bring them up to contextualize and demonstrate how relationships shape the way Indigenous People see the world. We sing songs to thank the earth and the directions, among other things. When we take from the earth, we leave offerings. Robin Wall Kimmerer writes about an experiment in her book, “Braiding Sweetgrass,” where her graduate student left 1/3 of a field of sweetgrass alone, 1/3 the sweetgrass was pulled up without care, but tobacco was left, and 1/3 was pulled up with care to preserve the roots and tobacco were left. She saw the sweetgrass that had been interacted with was flourishing, but the third left alone was withering away. She saw this and decided that humans are supposed to interact and be a part of nature and that we are not above or separate from it.

The unfortunate thing about the intersections of indigenous studies and cartography is that there is very little information to be researched. With our project being focused on the Midwest, there was even less, so we did deviate a bit in researching other locations. With this in mind, we can finally discuss maps.

This is how I discovered Jim Enote of the Zuni Nation, who believes that “more land has been lost to mapping than conflict.” He shows maps from the Zuni Nation, where the scale was optional. The map’s focus was showing the relationship between the subjects of the map. Having a relational map does not work to guide and record the way western maps attempt to do. Rather, it shows that history and stories are more important to the people. This is seen in wampum, where one can encode mnemonics for verbal maps.

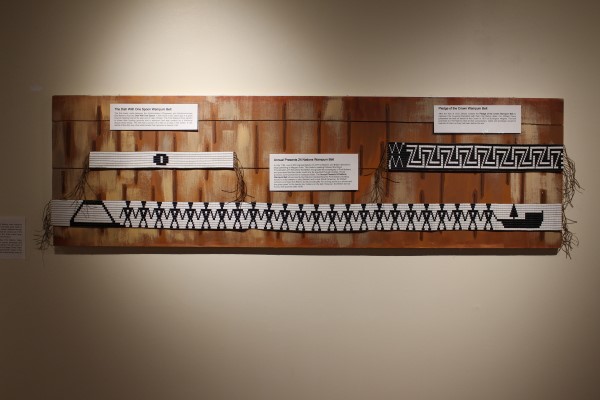

Wampum was used in this way, starting with first contact with colonizers. These recorded geopolitical and spatial relationships (Woodward 53). They also recorded specific treaties or agreements. This was not an “appropriate” way to map, and there have been maps found from nations like the Iroquois on birch bark, or animal skin that are more common. Wampum maps are highly stylized and they are intended to assist in memory.

The Iroquois used them most famously in the 5 nation belts. There was one for war, which was used during the period the nations were commonly at war. But there was also a peace belt, that showed figures holding arms to remind them that if anyone left their alliance, it would be severely weakened (Woodward 54).

Works Referenced:

Cordova, Viola F., and Kathleen Dean Moore. How It Is: The Native American Philosophy of V.F. Cordova. University of Arizona Press, 2007.

Heart, Bear, and Molly Larkin. The Wind Is My Mother: The Life and Teachings of a Native American Shaman. Berkley Books, 2010.

Woodward, David, and G. Malcolm Lewis. Cartography in the Traditional African, American, Arctic, Australian, and Pacific Societies. University of Chicago Press, 1998.

For more resources related to the Midwest Indigenous Cartography Project, see our project bibliography on Zotero.

Cheyenne Brenton is a research assistant on the Midwest Indigenous Cartography Project. They are a junior at Indiana University studying Philosophy.

1 Comment

This was very thought-provoking. I have never thought of mapping from this perspective. Western mapping is the only think I’ve ever been exposed to. The way Cheyenne describes indigenous mapping is a whole new think for me.