It’s difficult to even know where to begin. On July 24, I posted “A previously unknown IU pioneer,” detailing how I stumbled across an 1898 newspaper article about the first African American woman to enroll at Indiana University. As I mentioned in that article, this is history that had long ago been forgotten so for us, this was not only “new,” it was “news.” From the time I found that article, I spent the next two weeks as time allowed working to uncover anything else I could about “Miss Carrie,” as I’ve come to know her, but by the time of my blog post, I had decided I just had to put the project aside. My hopes were that someone else would come across my post in the same serendipitous manner and be able to help track down Carrie’s family so that we could obtain more information, a photograph, and to make certain they knew about her status at IU.

Well, from that little blog post came a tremendous amount of publicity, thanks to a LOT of help from my friends in IU and Library Communications. I had my first ever radio interview, several IU web sites wrote about it, and the story was even on the front page of the local newspaper, the Herald-Times (above the fold, which I’m told is a Big Deal). My call for help in finding out more about Miss Carrie had clearly been heard. I received several emails that helped point me to some resources I had not yet tried, including a database for historical African American newspapers, to which the IU Libraries has a subscription. In it, I got my first look at Carrie in a story about her high school graduation that appeared in the Indianapolis Freeman in 1897:

It’s not great but it was a start! Additional searches turned up more hits in the Indianapolis Recorder, a newspaper that has been in circulation for the African American community since the 19th century. In it, I found a very short article from February 1899 (after Carrie had left IU) that said, “Miss Carrie Parker has been obliged to discontinue her studies at the State University on account of nervous trouble. She hopes to resume work again at the beginning of the spring term.” The next month, they reported that Carrie and John G. Taylor had been married and that it “was quite a surprise to their many friends.”

Finding the family

These leads were enough to keep me going in my search for Carrie’s family. I won’t pain you with the all the details but I sent many emails and made many phone calls. From my previous research, I had found the census records that listed Carrie and John’s children and I had tried some half-hearted Google and Ancestry searches on them but I decided to give it another go. This time, my Google searches seemed to indicate there was some possibility that Carrie’s son Leon Parker Taylor was still alive. Surely that wasn’t right because he would be (counts on fingers) 99 years old. That had to be a mistake. But it kept turning up that Leon Parker Taylor was alive and living in southern Michigan.

So what’s an archivist to do? I called on my brothers and sisters in the information world, the public library of the little southern Michigan town. I know the librarian probably thought I was more than a little nuts as I told him my story but I gave him Leon’s information and asked if he could find out if he was indeed still living in their town of 12,000. By the end of day, my new best friend Earl had emailed me, confirming Mr. Taylor was still alive and gave me his phone number and address.

WHAT?

I KNOW!

The next morning, I called Mr. Taylor as soon as I thought it a decent time. He was unavailable but I talked to his daughter, Carol. I told her the story about how I had just “rediscovered” her grandmother Carrie Parker and that she was the first Black woman to enter IU. Carol’s response? “Oh yes, ma’am!” Apparently the family knew all along! She told me a few little tidbits about Carrie but said she wanted to save the storytelling for her father and he would call me back.

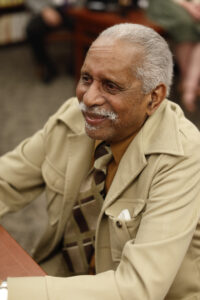

When Mr. Taylor called me, I just about fell in love. This man is incredibly sweet, incredibly sharp, and incredibly generous with his time. He talked to me about his mother a bit, said he would look for a picture of her but mainly he wanted to know, “How did you find me?!” Then he told me that because he was retired (I hope so!) and I had worked so hard to find him, he wanted to come to Bloomington to visit me. He would talk with his daughter and get back with me but he definitely wanted to come before winter.

WHAT?

I KNOW!

Well, he wasn’t wasting any time. Last Monday he called and asked if it would be okay for him, his daughter, and two nieces to visit that Thursday. It wasn’t a long drive and they just planned to come for the day.

I reached out to my friends throughout the University and we scrambled to roll out as much of the red carpet as we could with this short notice. You all, it was amazing. The family was wonderful. And the University overwhelmed them – in a good way – with its response to this rediscovery. At lunch, Vice President Yolanda Trevino told the family IU wants to work with them to develop an appropriate way to honor Carrie with a named scholarship or award. Then Kelly Kish from the President’s Office told them they plan to commission a portrait that will become part of the University’s permanent collection. Clarence Boone from the IU Alumni Association invited them all to return as guests of the University for this year’s Homecoming, at which time the Neal-Marshall Alumni Association will be celebrating its 40th anniversary. There may or may not have been a few tears shed and shared.

So what about Carrie?

Carrie’s story is truly an epic tale.

Her father, Richard, was born enslaved in 1834 in North Carolina. Upon emancipation, he retained the surname of his last enslaver, Parker, and settled in Enfield, North Carolina. In an autobiographical sketch obtained from the family, Carrie wrote that it was her mother, who could read and “loved the idea of schooling,” who persuaded her father to move to the north so that their children would have the opportunity to attend school. Thus the move to Clinton, Indiana, when Carrie was just over a year old. Sadly, the family arrived in January 1880 and on March 13, her mother died in childbirth. Her father wanted to move back home but his mother-in-law, who had traveled with them, convinced him to stay.

Carrie wrote,

Through his teaching and actions my father had instilled into our hearts that no one was better than we, unless he was a better Christian. With this belief in our hearts, none of us have ever been ashamed of our race and none of us could see why the so-called superior race could not see how foolish it is to believe otherwise.

Nonetheless, Carrie and her family faced discrimination — in church, in school, and in work. When Carrie finished middle school, the principal at the time had his own policy that no African American children would pass into high school. So he flunked her. Three times. She was determined to make it through or “die trying.” By the time she stood for her exams the third time, the citizens of the town were on her side and told the school not to interfere with her graduation; the school acquiesced and she finally passed on. She reported that the rest of her time at school went fairly smoothly and I’ve already reported in the previous post about the grand reception she received at her graduation.

The family did not have many details about Carrie’s time at Indiana University. She wrote that she “was not made to feel my color much while there” but as we already knew, she had to work to put her way through school. To do so, she lived with a faculty member and according to her granddaughter Carolyn, the wife heaped insane amounts of work on her and the faculty member was very generous in his interpretation of ‘other duties as assigned.’ So after a year of schoolwork, housework, and trying to keep out of the hands of the good Professor, Carrie decided she needed a break.

By this time she was engaged to John G. Taylor of Bloomington but planned to wait until she received her degree before marrying (the family thought he was also an IU student but the University has no record of such. I’ve not yet spent much time digging into his story). According to her memoir, when she took her break from school, John convinced her to marry him, promising to continue to finance her education. She later told IU folklorist Richard Dorson (more on this later!), “Every year I’d cry to go back” but she never again stepped foot on the Bloomington campus.

I still have much to learn about Carrie and her life but her family says she was a headstrong woman who said what she thought and fought for what she believed to be right. She wrote poetry, and instilled the importance of education upon her family. Her oldest son John graduated at the top of his high school class and received a scholarship to attend the Armour Institute of Technology (now the Illinois Institute of Technology), where he studied to become an electrical engineer. The plan was that he would come out of school, get a job, and then pay for Parker to also go to school for engineering and they would go into business together. John graduated in the top third of his class but when he came out of college in the early 1930s, the country was deep in the Great Depression. Couple that with his race (according to Parker, there were only three black electrical engineers in the country at the time), and John was unable to secure an engineering position. Anywhere. Ever. So he worked for the post office and Parker had to put aside his dreams of attending school.

Karen Land of IU Communications found in Google Books that IU folklorist Richard Dorson had talked to Carrie and her sister Lulu in the 1950s when he was in Michigan doing fieldwork for his book Negro Folktales in Michigan. What’s more, IU’s Lilly Library holds Dorson’s papers, which includes all of his notes from this trip. Lulu and Carrie primarily told Dorson slave tales passed on from their father but there is also an amazing short life history Dorson collected from Carrie.

I know I will see the family again (and perhaps meet more) when they return in October, so this story is far from over. But let me share just a few more thoughts with you.

At the Society of American Archivists meeting this year, the Society released a new marketing campaign: Archives Change Lives. I long ago drank the water and believed this. But this. This has proven to me that even an institutional archives can play a part.

#archiveschangelives

Leave a Reply