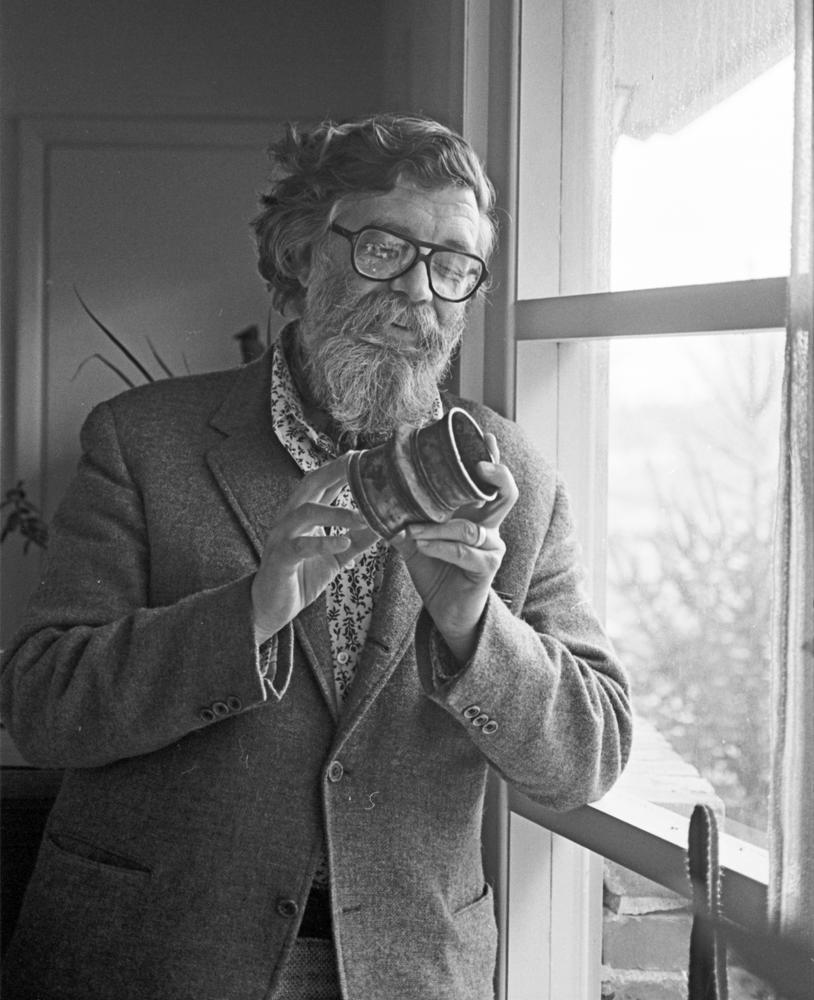

Roy Sieber was a historian of African art who taught at Indiana University Bloomington from 1964 through 1983. He was the first person to receive a degree in African art in the United States, essentially founding the discipline of African Art studies in this country.

As part of his efforts to document the artistic traditions of West Africa, particularly Nigeria and Ghana, Sieber became well known for his photographs of African art and performance. The Roy Sieber papers at the IU archives, contains black and white photo prints and hundreds of slides of African artwork in use during ritual celebrations and on display in museums, as well as annotated bibliographies written by Sieber’s students providing historical context for specific ethnic groups. Sieber’s career spanned several decades, and the black and white prints in the collection were taken in two time frames: Sieber’s first trip to Nigeria in 1958, and his 1971-1972 trips to museums in various countries with large collections of African art.

While the photographs in this collection depict many different ethnic groups in Nigeria and many different types of art and performance, two particularly striking series of photos document Igala masquerade dances. The Igala people live in the Benue River Basin and a number of Igala villages appear in this collection. While masquerade traditions appear throughout Nigeria and in other parts of West Africa, the style of the mask and dance and the oral narratives associated with those traditions vary widely between regions and ethnic groups. Scholars have suggested that Igala masquerades, much like other parts of their culture, reflect a complex history of conflict, trade, and cultural diffusion with other communities and ethnic groups.

The interactions that have shaped these traditions make it difficult to isolate a uniquely Igala masquerade style, and the many different iterations make it challenging to find information about particular villages’ masking traditions. However, it is evident that as with the masquerades of other ethnic groups, most Igala dances are celebrated on two festival days, one during the rainy season and one during the dry season. These festivals honor ancestral figures and celebrate the agricultural cycles. Additionally, many of these masked dances reflect and reinforce the social and political hierarchies and historical narratives of a particular community.

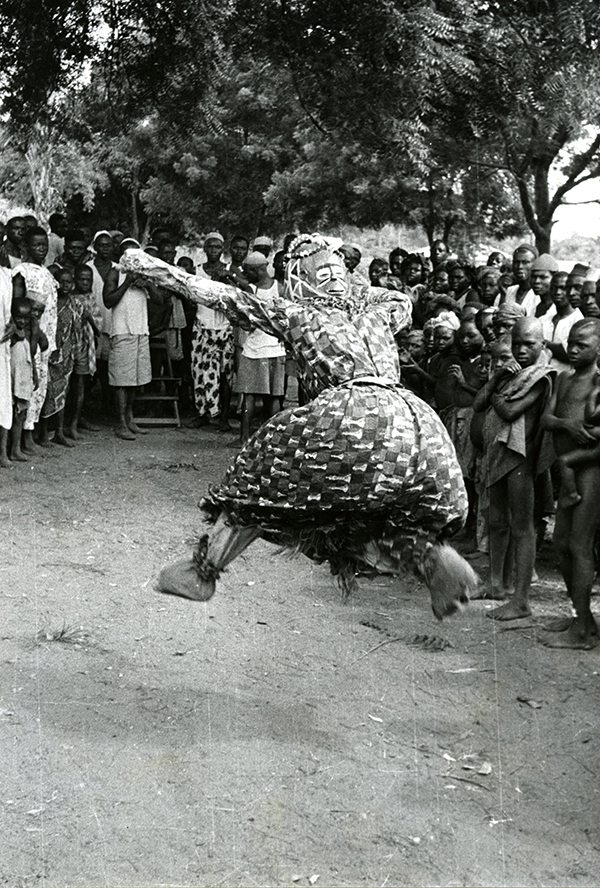

In the first series of photos below, taken in Okpo village, the caption clarifies that the dancer is wearing an “Egu” mask called “Egodoji,” and that the drums being used are “okelegu,” meaning they are beat with two hands. The text also notes that the mask is Janus-faced and made of painted, carved wood, while the rest of the costume is cloth. In this context, “Egu” refers to the type of festival as well as the mask and dancer; the word has been translated various ways, but scholars have translated it as “spirit” or “dance,” and is associated with annual festivals to honor ancestors and the history of a particular ethnic group.

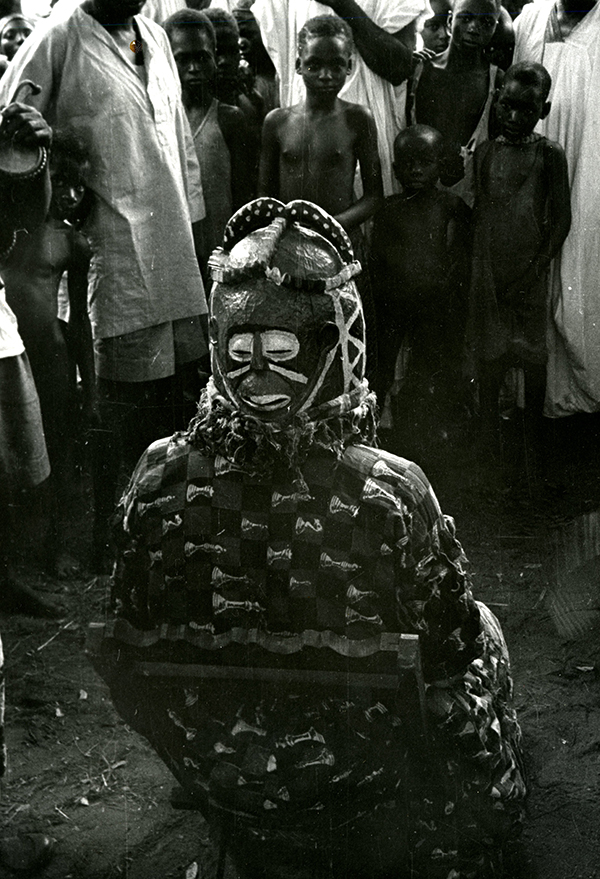

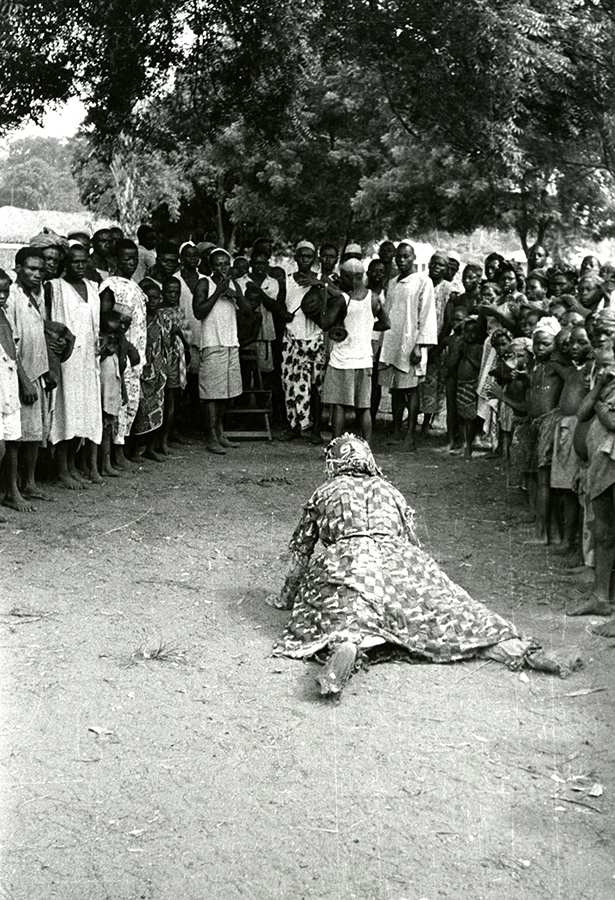

The second series of photos were taken in Inye village, and the three masks seem to depict potential roles within a marriage. The caption states that the largest mask represents the husband, and is called “Ikonyi,” or “big mouth too big,” while the mask representing the older wife is named “Odomodo,” or “too big,” while the mask representing the younger wife is “Ikekemede,” or “quarrelsome woman.” Sieber notes elsewhere that the husband, Ikonyi, is performed in a “threatening manner” and restrained by a rope around his waist. The three masks always appear together, and seem to constitute a humorous engagement with the practice of marriage and the conflicts produced by that relationship.

While Sieber does not provide more context about the spirit in which these masks are intended or received, it is apparent that they are important enough to be performed consistently. Masks are often passed down from one owner to another and can last many years. The mask called Egodoji is a Janus-faced helmet mask, a style that appears in both central and west Africa. Helmet masks are associated with depictions of local ancestry and royal lineages. The masks of the husband and wives, on the other hand, are “horizontal masks,” which often have animal attributes and are associated with “potent sorcery and spirits.” Considered together, these two sets of photos suggest that the masquerades may be used to associate marital responsibilities and the identity of ancestors or royal figures with the attributes of spirits, animals, or the natural world.

1 Comment

Beautiful collection! Thank you for sharing