From November 18 to December 19, 2009, a special exhibit at the Lilly commemorates the publication of Darwin’s Origin of Species. The location of the exhibit in the Lincoln Room is particularly appropriate, since Darwin and Lincoln were born on the same day, on February 12, 1809, a coincidence that has led the New Yorker’s Adam Gopnik to label them the two “midwives to the spirit of a new world.” Gopnik’s Angels and Ages is just one of many books published in time for the Bicentennial that celebrate Darwin as a heroic, near–saintly battler against Victorian convention. By contrast, the Darwin highlighted in this exhibit is more hands–on: a thoroughly social and sociable being, a man equipped with an excellent sense of humor and a keen awareness of his popular appeal. The five cases of the exhibit track his career from the publication of Darwin’s first bestselling book, the Journal of Researches, now generally known as the Voyage of the Beagle, to his last popular success, The Formation of Vegetable Mould through the Action of Worms, in which he wanted to find out, among other things, if worms were susceptible to music (they weren’t). Unpublished letters (one of them even unknown to Darwin scholars) round off the image of a fluent writer who rebelled against the idea that scientific writing had to be, in the caustic words of Darwin’s admirer Stephen Jay Gould, “boring, inaccessible, illiterate, or unreadable.”

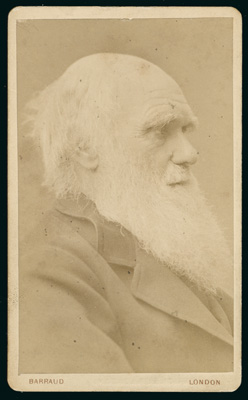

Highlights include a rare first edition of Origin as well as a late printing, annotated by his son Francis. The latter was originally in Darwin’s library at Down House and was recently purchased with the help of the Friends of the Lilly Library. Another new acquisition, the American edition of Origin, published by Appleton in New York, thanks to the Harvard botanist Asa Gray (1810–1888), Darwin’s most important supporter in the United States. Thanks to Curator of Manuscripts, Cherry Williams, we also now own a late carte–de–visite, likely one of Darwin’s last images from life.

Darwin’s friend Gray, a devout Presbyterian who did not work on Sundays, had hoped that there would be a way to reconcile evolution and faith. Difficult as it may be to assume that divine purpose governed natural selection, he wrote in his book Darwiniana (a first edition is on display at the Lilly), the alternative was even less satisfactory. Darwin politely disagreed. Would God have wanted to design a world in which cats cruelly play with mice? The subject was, he felt, too profound for the humans to comprehend—as if a dog wanted to understand Isaac Newton. Said Darwin, “Let each man hope and believe what he can.”

The exhibit is accompanied by a free, illustrated catalogue, written by the curator.

– Christoph Irmscher, Exhibition Curator and IU Professor of English

View a larger image of Charles Darwin.