Madeline Kripke’s collection includes many rare books, some of them classically rare — old books of status for which collectors compete at auction — and some of the ephemera made rare by attrition, because no one thought them worth keeping until there were next to no copies left to collect. Unique books, however, are the rarest of all, and Madeline collected at least one such book of interest, custom made for a readership of one, though now that it’s in the Lilly Library, it may find more readers than anyone would have expected.

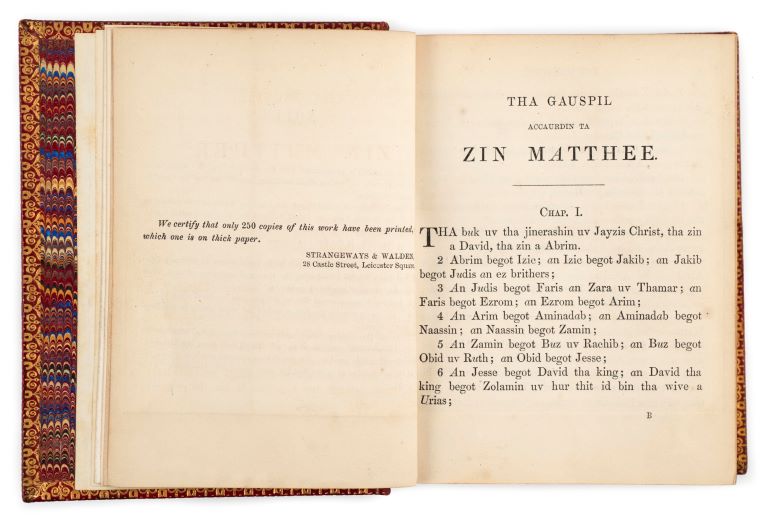

There’s a backstory. Louis-Lucien Bonaparte (1813–1891), nephew of the infamous emperor Napoleon I, was a prominent philologist, born in England while his parents were captive there, raised on the Continent, and then resident again in England again from 1852 until the end of his life. In the 1850s, he organized a series of publications, translations of the Gospel of Matthew and the Song of Solomon into English dialects, to illustrate variation in English at the time. They appeared in limited press runs (250 copies each) in the late 1850s and early 1860s. We wouldn’t approach variation this way today — we’d do field research — but just registering regional variation and making samples of it somewhat accessible was a step forward at the time. There were lots of gentlemen (gentlewomen, too, but Bonaparte seems to have overlooked them) who had both the requisite time and skills. Some were already well-established commentators on specific dialects. For instance, Abel Bywater had published a glossary of the Sheffield dialect (1839) — Madeline owned a copy, of course — and Bonaparte enlisted him to translate the Song of Solomon into that dialect for his project. The John George Forster who provided a translation in Newcastle English may have been the same John Forster who was Charles Dickens’ friend and biographer — he was a native of Newcastle, and he and Bonaparte were both members of the Athenaeum.

Another of these contributors brings us to the artifact of interest in Madeline’s collection. Henry Baird (c1829–1881), a solicitor’s clerk and journalist resident at Exeter, was the author, as “Nathan Hogg,” of poems in the Exeter dialect published first in newspapers and then collected (c1847) — they were quite popular. A second series of poems, published in 1863, is dedicated to Bonaparte who, we’re informed, stimulated publication by visiting Baird in Exeter because he was so taken with the first collection. But that’s not the full story, as Madeline’s artifact proves.

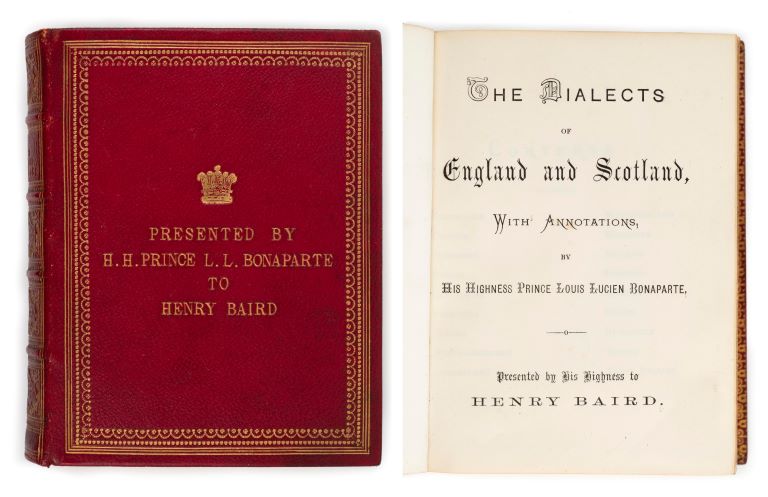

Madeline’s book assembles twenty-five of the translations, uniformly printed for Bonaparte by George Barclay (28 Castle Street, Leicester Square) and Strangeways & Walden (the successor firm, same address) at 4 x 5 3/8 inches, bound in bright red leather with gold lettering, gilt edges to the pages. The spine communicates the volume’s title, The Dialects of England and Scotland, reiterated on the title page, “with Annotations by His Highness Prince Louis Bonaparte.” There is no explicit date, but the latest of the pamphlets included, in fact Baird’s Devonshire Gospel of St. Matthew, is dated 1863, the culmination, as it were, of Bonaparte’s ambitious scheme. The book’s cover is stamped with the following:

PRESENTED BY

H. H. PRINCE L. L. BONAPARTE

TO

HENRY BAIRD

which also appears on the title page. The volume includes two pictures of Bonaparte tipped in on blank pages, and Baird pasted three letters from Bonaparte among the contents. In other words, the book Madeline collected is unique, a personalized presentation copy of various works, including some of Baird’s, further personalized by Baird’s insertions. Possibly, Bonaparte assembled such copies for all of his translators, but I have yet to locate any but the copy presented to Baird.

Thus, a unique book in several dimensions. I tend to think of items like this one as “priceless,” but really one can’t claim that, because price depends on someone caring enough to pay for it. A bookseller once agreed with me about this specific book, pricing it at £1800, which early in the book’s history was quite a sum. But I have found, I think, from whom Madeline bought it, and by then the price — though in my view not the value — declined considerably. Lawrence’s Auctioneers of Crewkerne, in the county of Somerset, announced an auction of books for 2 February 2012 in a catalogue of the kind Madeline — indeed, any collector like Madeline — scoured for worthy purchases, and there it is, on page 245, lot 2319, not merely described but pictured so that one may read the cover, and marked at £250–350. Were the bidding fierce, of course, the cost to Madeline might have been considerably higher, but we have yet to find a record of the purchase.

I have no doubt that Madeline would have paid considerably more than Lawrence’s expected, just as I have no doubt that she paid just what she needed to pay. She slipped the book into a plastic sleeve and there was room in that sleeve for yet another sleeve containing a pamphlet-sized (34 pages) Catalogue des Ouvrages de Linguistique Européenne Édités par le Prince Louis-Lucien Bonaparte, published in 1858 in 250 copies by George Barclay, at that time also busy with Bonaparte’s dialect translation project. The mini-catalogue includes entries for three lowland Scots translations by H. S. Riddell, as well as translations by Forster (Newcastle), John Rayson (Cumberland), and the Reverend John Richardson (Westmoreland), so it is closely associated with the book presented to Henry Baird.

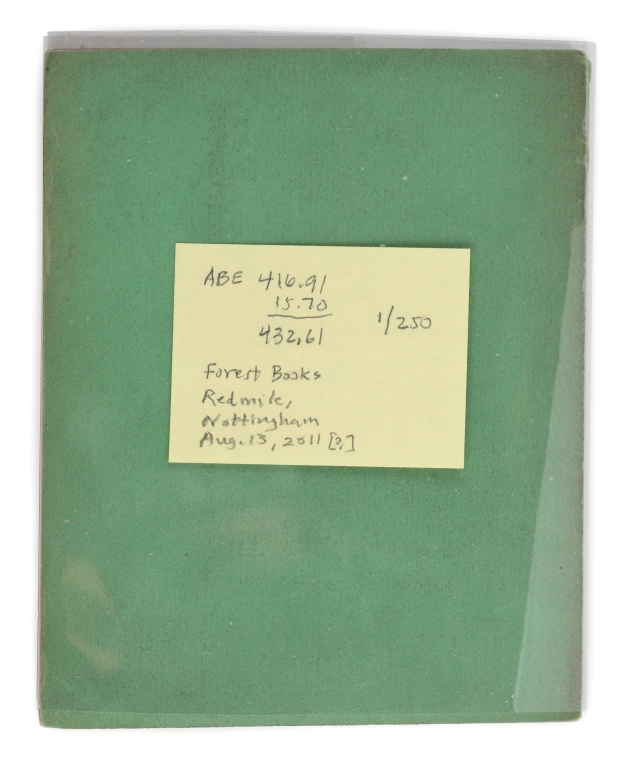

There is a sticky note on the pamphlet sleeve suggesting that the catalogue was purchased from Forest Books in Redmill, Nottingham on 13 August 2011; then, there’s a sum labeled “ABE” — sale price plus shipping — totaling “432.61.” An earlier seller had marked the pamphlet as “3 —,” but whether pounds or dollars is unclear. Either way, if Madeline was willing to spend that kind of money on the pamphlet, she certainly would have gone further to buy Bonaparte’s gift to Baird. One suspects a plan to collect everything relevant to Bonaparte’s philological studies, unrealized.

Leave a Reply