By Katherine Reed, PhD candidate, University of Manchester

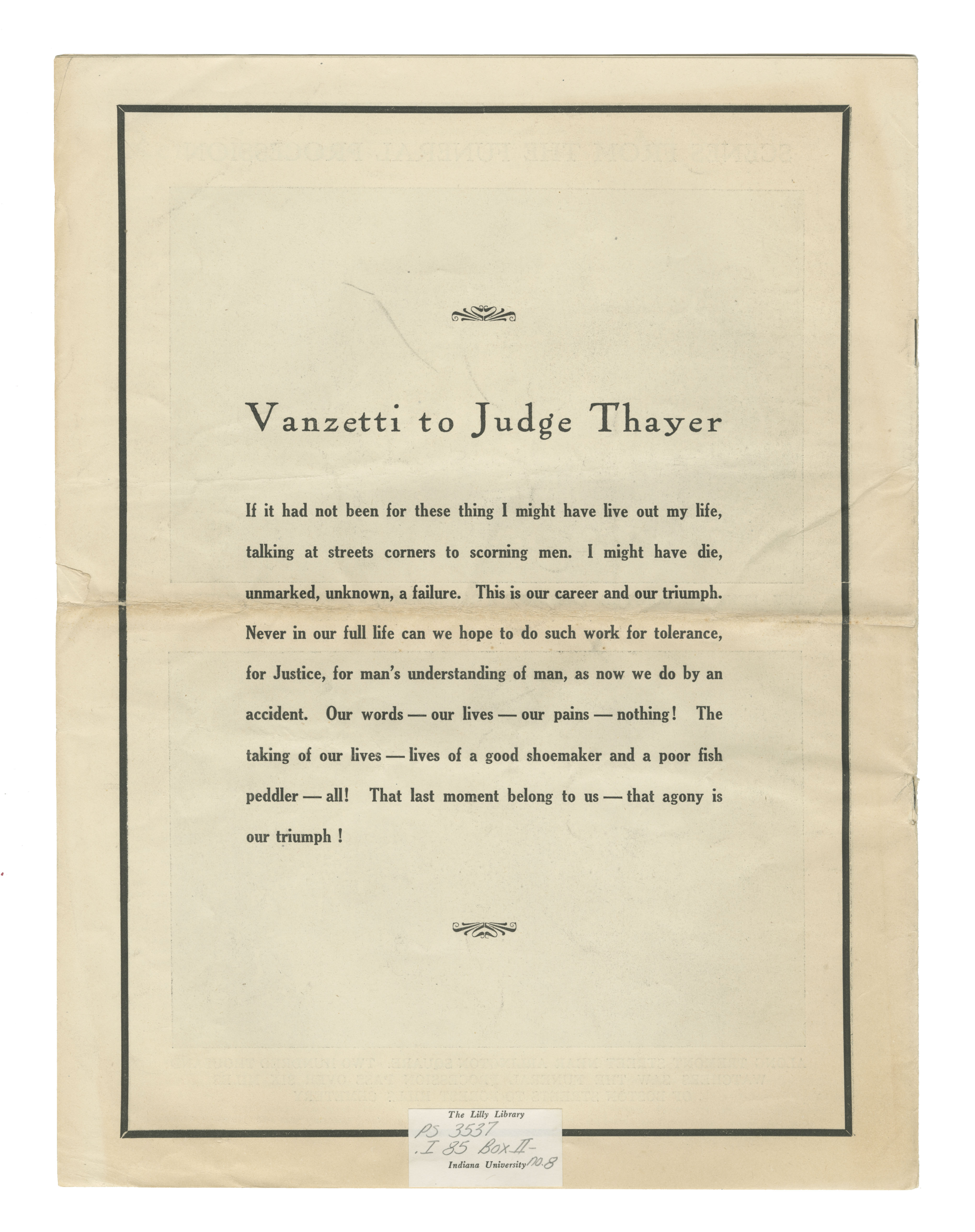

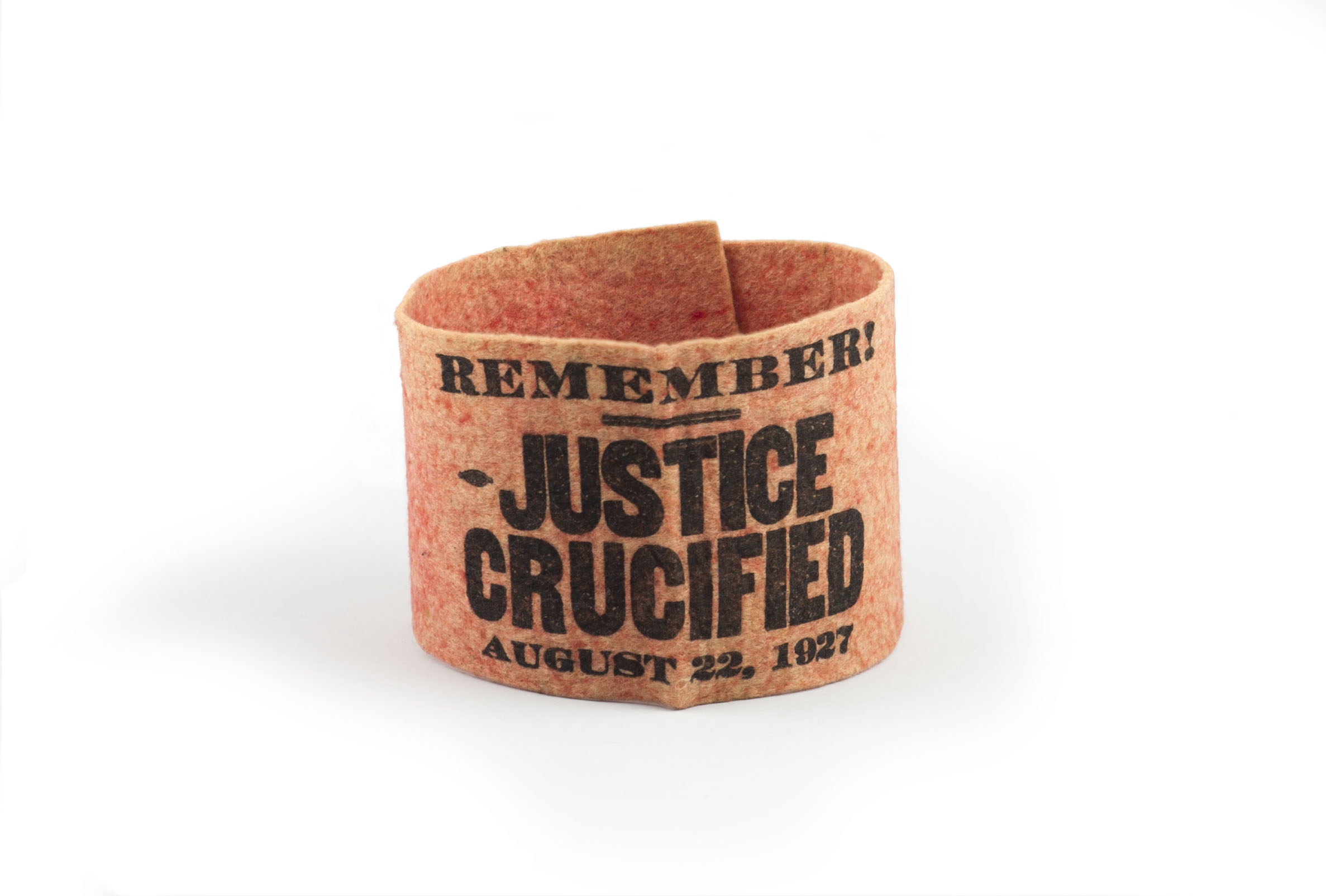

August 23, 2017 is the 90th anniversary of the executions of the anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti. Accused of a crime they probably did not commit, in the midst of the Red Scare, their case became a liberal cause célèbre in the 1920s. Having Dorothy Parker, John Dos Passos, H.G. Wells and Albert Einstein on their side turned out not to be enough to save them from the electric chair. However, the fact remains that they inspired remarkable support. It helped their cause that Vanzetti was a charismatic wordsmith. Perfecting his English in prison, he wrote hundreds of letters and impressed visitors with his eloquence. His most famous statement, made in 1927, ended: “Our words – our lives – our pains – nothing! The taking of our lives – lives of a good shoemaker and a poor fish peddler – all! That last moment belongs to us – that agony is our triumph!”

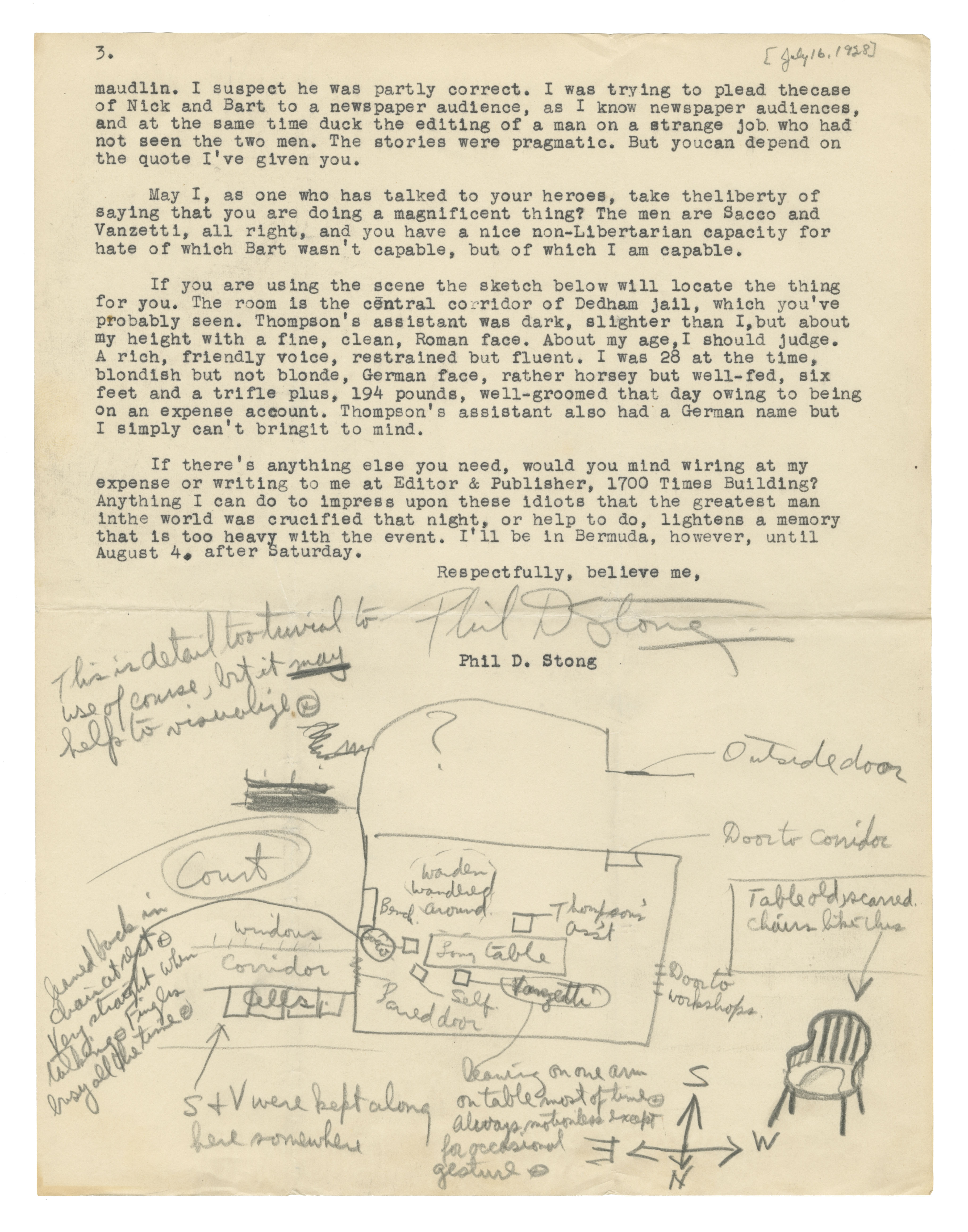

At first, the words were erroneously and emotively attributed to a speech Vanzetti had made in court. Publicity materials produced by the Sacco-Vanzetti Defence Committee, and the first edition of the prison letters, claimed he had said it to the Judge on the day the death sentence was pronounced. Its origins were in fact in an interview by the reporter Philip Stong who met with Sacco and Vanzetti at Dedham Jail in the spring of 1927. At the time, Stong claimed he had added nothing except exclamation marks. Despite this, scholars have taken the famous spiel with a pinch of salt (Russell, 1962: 388). Although Vanzetti was indubitably eloquent, there has been a general inkling that the statement must have been polished up for print. Tucked away in the Lilly Library archive is a fascinating letter by Philip Stong which breaks down, sentence by sentence, which words came verbatim from Vanzetti (or at least, were scribbled down fairly accurately in a hotel room later) and which had benefitted from journalistic fairy dust. Perhaps predictably, the most famous phrase of all – “a good shoemaker and a poor fishpeddler” – was a fiction. The letter, dated July 16, 1928, was written to the author Upton Sinclair who was researching a novel about the case.

Having achieved fame with the muck-raking The Jungle back in 1906, Upton Sinclair had won good reviews for Oil! in 1927 and intended to cement his literary reputation with an ambitious “contemporary historical novel” about Sacco and Vanzetti (Sinclair, 1929: 5). Sinclair pestered everyone involved in the case for facts and insights. Phil Stong was responding to such a plea. It is notable that when younger writers wrote to Sinclair they often tried to impress him with their prose. Their missives, strewn throughout the Lilly Library’s Upton Sinclair collection, are littered with gaudy sentences, flattery and the swagger of swear words. Phil Stong’s letter, although in the same genre (he praises Sinclair as “a fine artist”), transcends this. As a writer, he clearly had talent to burn. It is hard to dislike someone who describes themselves thus: “I was 28 at the time, blondish but not blonde, German face, rather horsey but well-fed, six feet and a trifle plus, 194 pounds, well-groomed that day owing to being on an expense account.” Sinclair nabbed whole sentences from the letter for use in his novel, including the jokes.

Phil Stong had visited Sacco and Vanzetti during a strange Indian summer of their imprisonment. Having been, after years of appeals, finally sentenced to death, they were allowed such luxuries as an hour a day playing bocce in the yard. During most of their imprisonment, the men had been in separate jails. For these few months, they were together in Dedham, a gaol made to sound rather picturesque by visiting writers. John Dos Passos described it as “airy, full of sunlight…a preposterous complicated canary cage” (Dos Passos, 1927: 69). Stong later reminisced that, “It is odd to speak of a prison as pleasant, but this one was” (Leighton, 1949: 185). During the interview, both the reporter and the two men were far too polite to mention the electric chair. The thought was ever-present nonetheless. Stong said that Vanzetti’s famous statement, or a version of it, was intended to comfort him.

In shaping the words for a newspaper audience, Stong admits that he might have “got that last bit a little more oratorical than Bart made it” but the gist was the same. A few liberties were necessary to “inject that humility and simplicity that was in his presence into my story.” He wrote to Sinclair, “I will confess to you, what you will not let anyone else learn, that Bart said it, somehow more simply, more powerfully and touchingly.” Here is the annotated version of Vanzetti’s statement, which Phil Stong gave Sinclair, based on his notes from the day:

“If it had not been for these thing,” says Vanzetti, “I might have live out my life, talking at street corners to scorning men. I might have died, unmarked, unknown, a failure.” (Note how he recalls himself from his personal determination and includes Sacco, now. I remember this distinctly.) “Now we are not a failure. This is our career and our triomph. Never in our full life can we hope to do such work for tolerance, for joostice, for man’s onderstanding of man, as we do by an accident.

(This is approximate and you may take liberties with it.) “Our words – our lives – our pain – nothing! The taking of our lives – lives of a good shoemaker and a poor fishpeddler – all!”

(This is exact): “The moment you think of belong to us – that agony is our triomph.”

Then they shook hands and went back to their cells.

Katherine Reed is a History PhD student from the University of Manchester who took part in the John Rylands Research Institute/Lilly Library Doctoral Research and Training Program in 2017. Read more about the program here.

References

Avrich, Paul. Sacco and Vanzetti: The Anarchist Background. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1991.

Dos Passos, John. Facing the Chair. Boston: Sacco-Vanzetti Defence Committee, 1927.

Leighton, Isabel, ed. The Aspirin Age 1919-1941. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1949.

Russell, Francis. Tragedy in Dedham. London: Longmans, 1962.

Sacco, Nicola and Bartolomeo Vanzetti. The Letters of Sacco & Vanzetti. London: Penguin Books, 1997.

Sinclair, Upton. Boston. London: T. Werner Laurie Ltd., 1929.

Tejada, Susan. In Search of Sacco and Vanzetti. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2012.

Leave a Reply