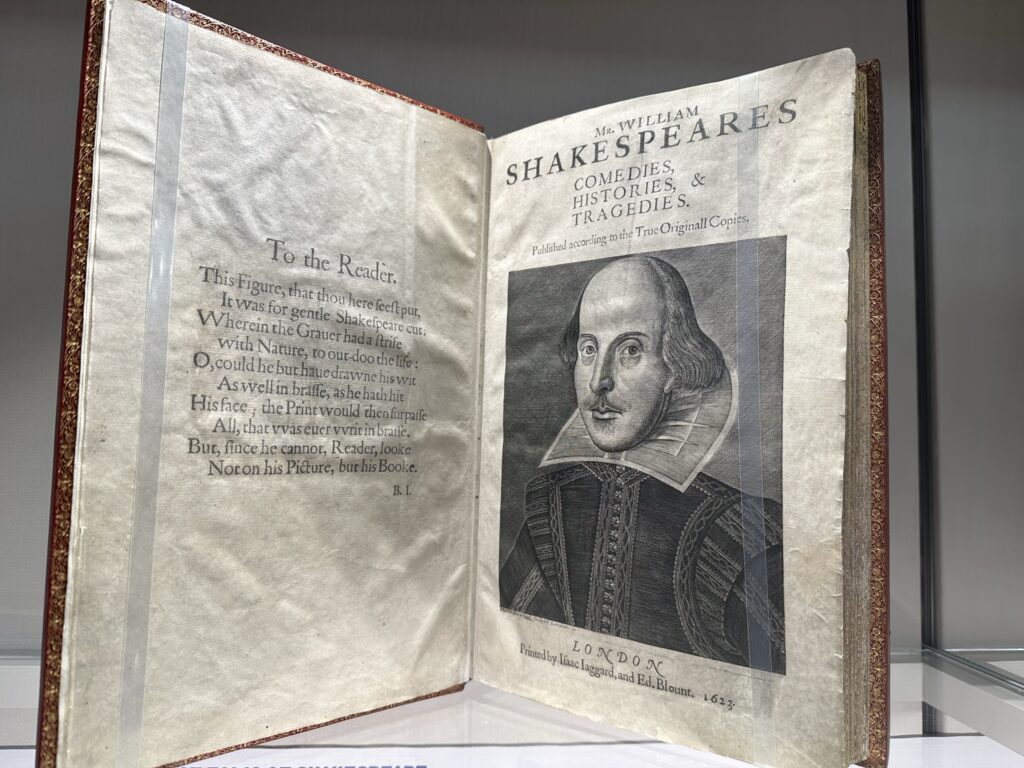

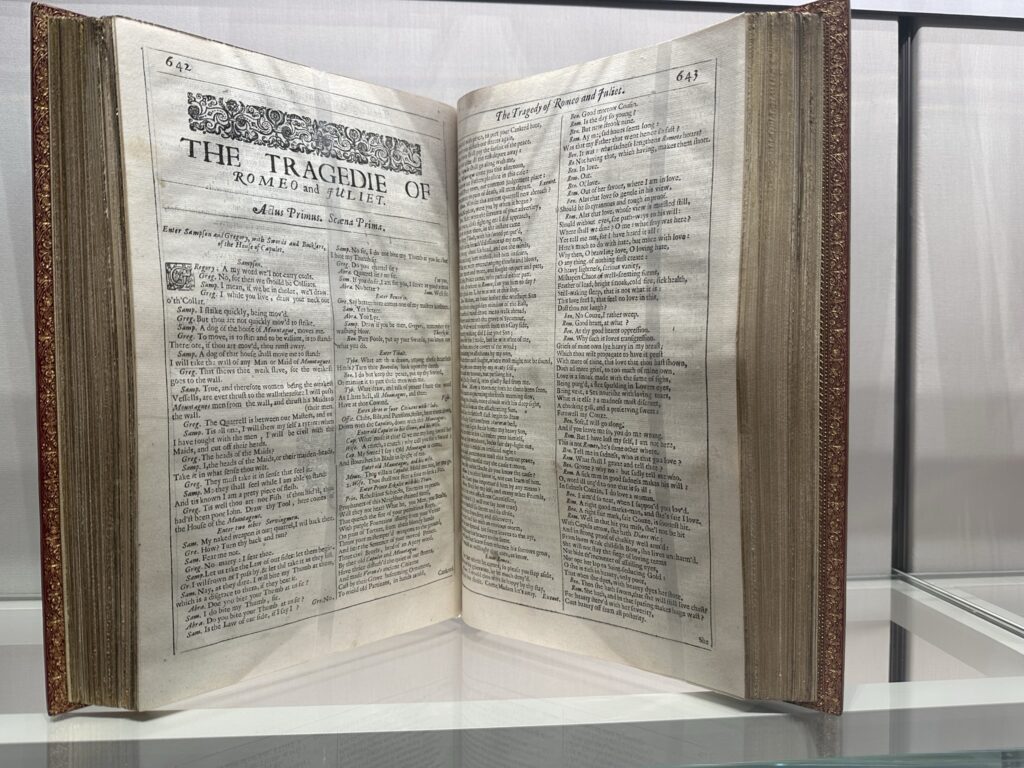

This spring, the Lilly Library is celebrating the 400th anniversary of the Shakespeare First Folio. The First Folio, printed in 1623, is fundamentally how we know Shakespeare. Eighteen of the thirty-six plays had previously been published in a smaller quarto format, sometimes with significant textual differences, but the rest of the plays likely would not have survived had this project not been undertaken after Shakespeare’s death by his friends and colleagues.

In this blog post, exhibition curators Rebecca Baumann and Maureen Maryanski share some of their favorite items and stories from the exhibition. Stop by this spring to see these and many more items from the Lilly Library’s collections related to the life and work of William Shakespeare.

The Third Folio of Shakespeare

The centerpiece of this exhibition is, of course, the spectacular First Folio of Shakespeare’s works. But the Lilly Library also holds the Second, Third, and Fourth folios of Shakespeare, and each is special for many reasons of their own. We especially love the Third Folio (1664), which is, surprisingly, the rarest of the four. According to the Shakespeare Census, there are 228 surviving copies of the First Folio, 371 of the Second, only 180 of the Third, and 337 of the Fourth.

This relative rarity is likely due to the fact that many copies were destroyed in the 1666 Great Fire of London. The fire swept through the city on September 2 through 6, 1666, consuming almost everything from Fleet Street to the Tower of London. While most historians believe that the human death toll of the fire was relatively low, the destruction of cultural heritage was devastating, including the loss of thousands of books and manuscripts in private libraries, the stock of booksellers, and printed and unsold books in printing shops. The unsold sheets of the third folio were among the casualties. One contemporary commentator (W.G. Bell, The Great Fire of London, 1666) noted “Never since the burning of the great library at Alexandria has there been such a holocaust of books.”

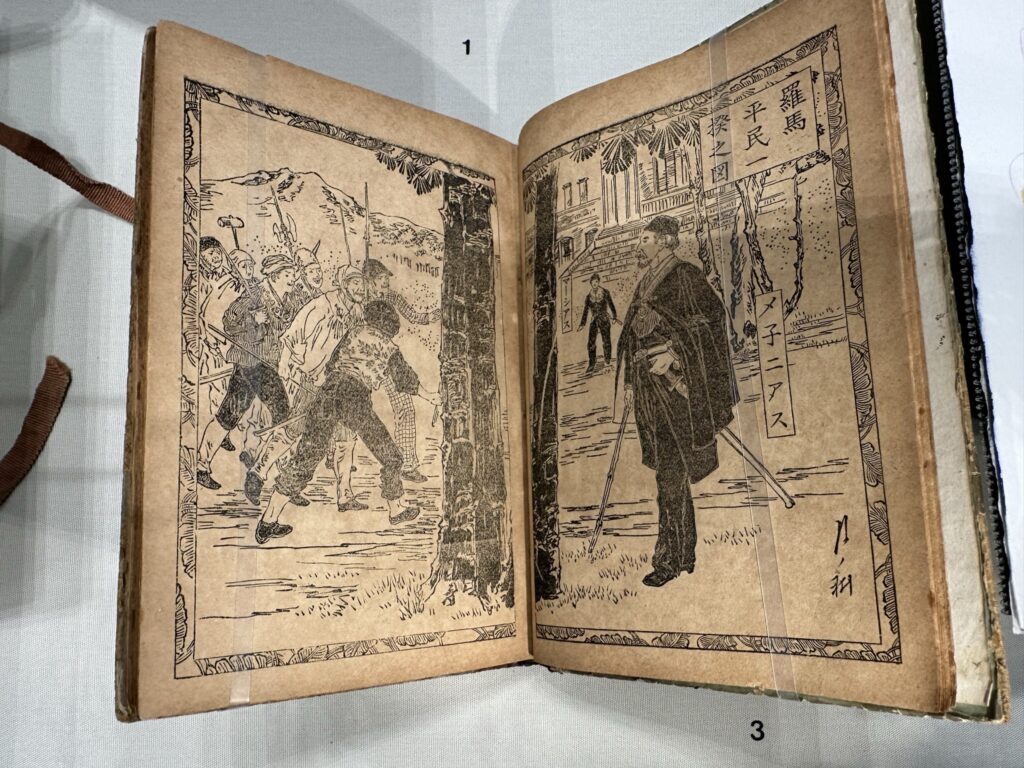

Japanese Coriolanus

This 1888 free translation and adaptation is most likely the first full translation of Shakespeare’s Coriolanus published in Japanese. Accompanying the text are eight illustrations by celebrated artist Ogata Gekko (1859-1920), who was especially known for being self-taught and designing ukiyo-e woodblock prints. This book was purchased specially for this exhibition from Hozuki Books.

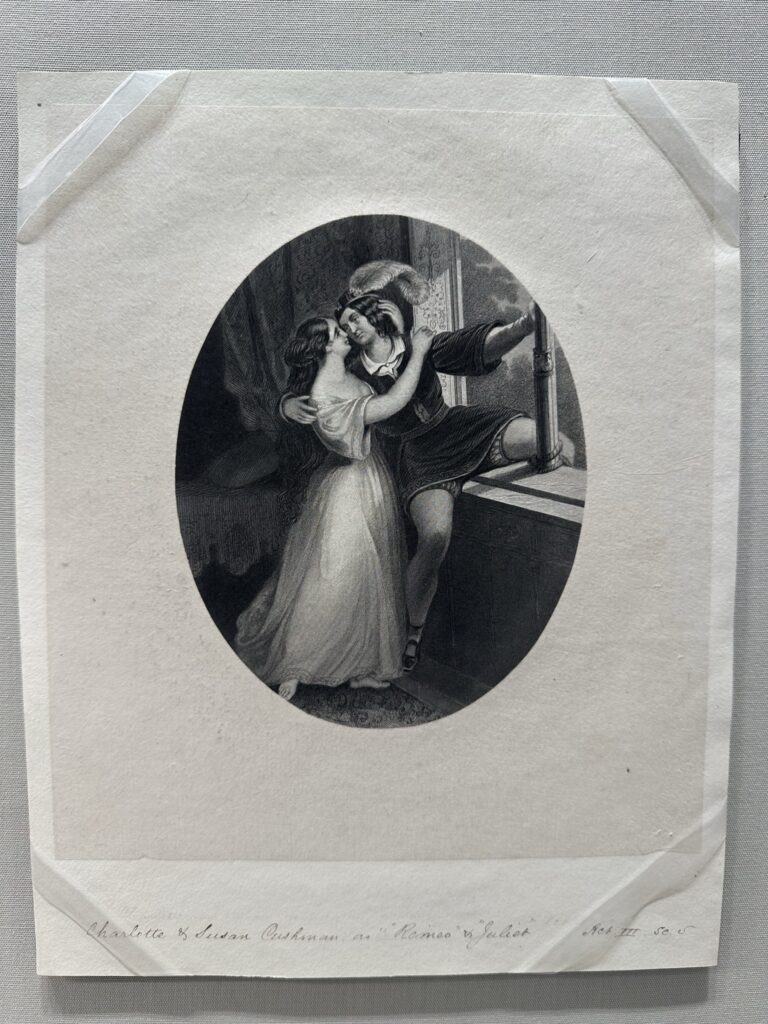

A Sapphic Romeo and Juliet

Many people know that during Shakespeare’s lifetime, female parts were played by male actors. But few people know that some 19th-century performances of Romeo and Juliet featured female actors in both leading roles. Sisters Charlotte and Susan Cushman were celebrated American actresses who became famous for playing Romeo and Juliet together in the mid-1840s. Charlotte, the older of the two, made her stage debut in 1835 and became the most famous American actress of the 19th century, lauded for playing men’s roles like Romeo. Charlotte also lived publicly as a queer woman, romantically involved with artist Rosalie Sully, writer Matilda Hays, and sculptor Emma Stebbins, the first woman to receive a public art commission in New York City for Angel of the Waters (1873) atop Bethesda Fountain in Central Park. The angel is said to be inspired by Charlotte.

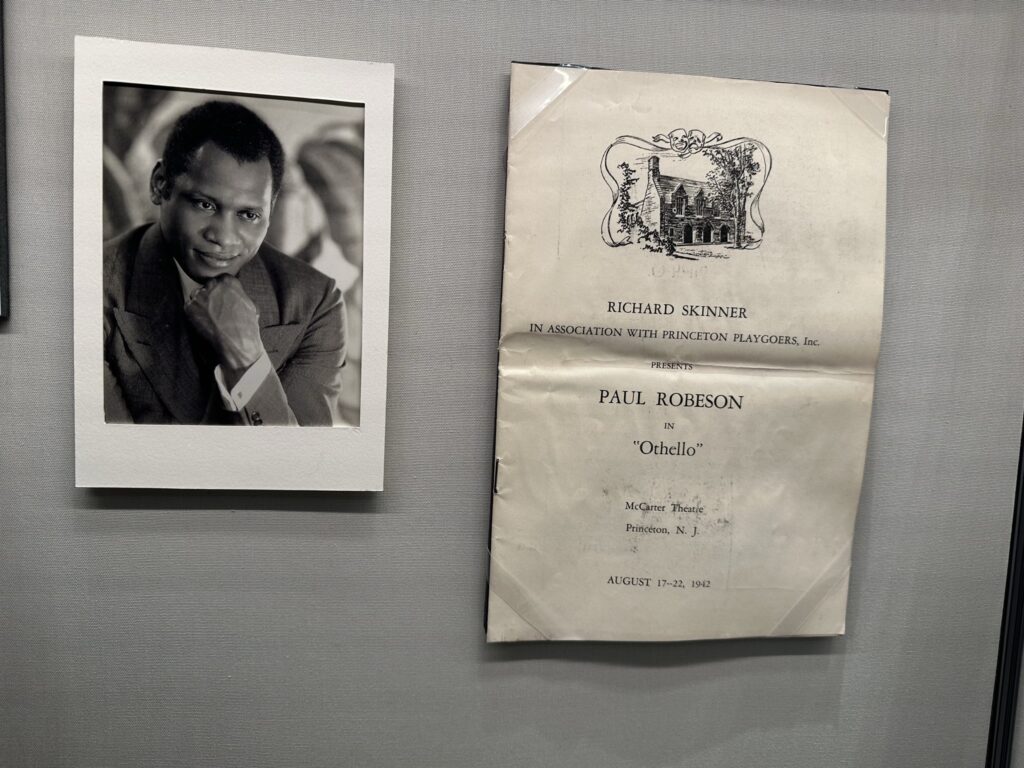

Shakespearean Actor Paul Robeson

Paul Robeson was the first Black actor to play to play the role of Othello on Broadway with a white supporting cast. The Broadway version ran from 1943-44, but Robeson had been playing Othello in Britain since the early 1930s. The Lilly Library’s collection includes a program for a production at the McCarter Theatre in Princeton, New Jersey in 1942, a precursor to the Broadway production. Also shown here is a postcard of Robeson from the collection of author and IU professor Don Belton, whose papers, including a postcard collection focused on Black celebrities, are part of the Lilly’s collections. Not shown but also in the exhibition is a first-hand account of a playgoer who saw Robeson perform the role in 1942 and raved that Robeson was “the greatest man this country has produced in this generation” and optimistically hoped that his casting in the play would “finally conquer prejudice and Jim Crow.”

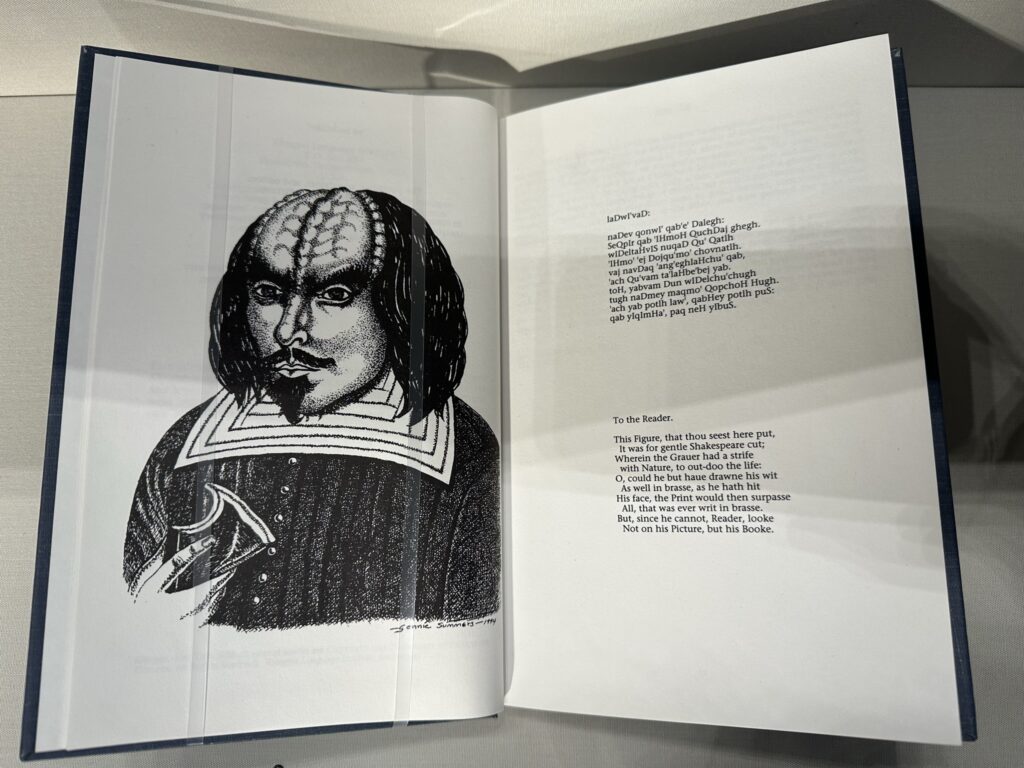

Shakespeare in the Original Klingon

This unusual 1996 edition of Hamlet was translated into Klingon by Nick Nicholas and Andrew Strader and published by the Klingon Language Institute, a group founded in 1992 by Star Trek fans to promote the Klingon language and culture. The inspiration for this work came from a line in Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country in which Chancellor Gorkon says, “You have not experienced Shakespeare until you have read him in the original Klingon,” implying that Shakespeare was actually a Klingon (Wil’yam Sheq’spir) who wrote a bloody tale of honor defiled in an attempted coup of the Klingon Empire.

These books are just a small sampling of the items on display in our current exhibition. Stop by to see dazzling artists’ books, gorgeous illustrated editions, fine bindings, charming miniature libraries, and much more! The exhibition runs through this summer and is free and open to the public. Free drop-in tours of the public galleries happen every Friday at 2:00.

Rebecca Baumann, Head of Teaching & Research and Associate Curator of Modern Books & Manuscripts

Maureen Maryanski, Education Librarian

Leave a Reply