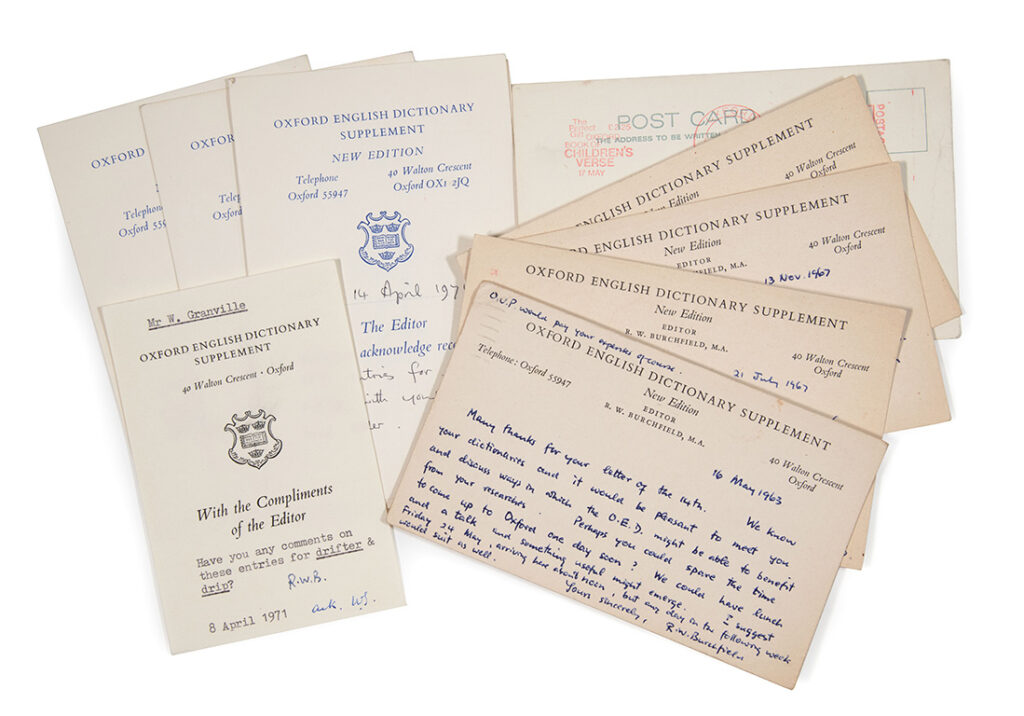

One of the most satisfying moments in unpacking the Kripke Collection so far was when I reached into a box almost but not quite full of books and pulled out a plastic box filled with postcards. A box inside a box — who can resist excitement at such a moment? What would the postcards reveal?

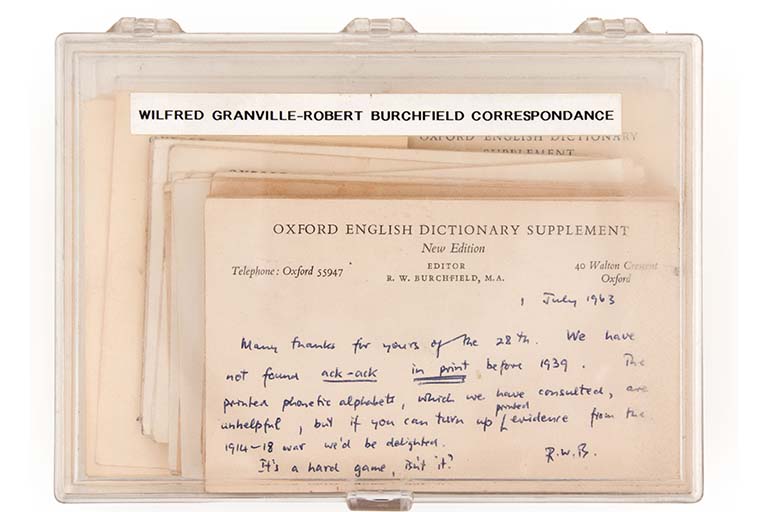

There are 140 of them, dated from 1963 to 1973, all addressed to W. Granville, Esq., Shakspere Cottage, 8 Eastern Road, East Finchley, London N.2. The W. is Wilfred, and Granville was among other things, author of The Theater Dictionary (1970) and Dictionary of Sailors’ Slang (1962). He also contributed significantly to the Supplement to the Oxford English Dictionary (1972–1986).

Historical dictionaries like the Oxford English Dictionary and its Supplement illustrate the meaning and usage of words, not just in definitions but in dated quotations. Indeed, A. J. Aitken, who was for a long-time chief editor of the Dictionary of the Older Scottish Tongue, wrote on more than one occasion that the quotations are primary and definitions a scaffold on which they’re organized. Big historical dictionaries cannot afford to hire enough staff to read texts and cull quotations, so they rely on volunteer readers and, occasionally, proven readers who contribute so much so well that they are paid for their work. History overlooks most volunteer readers. They’re not lexicographers, many would say — I’m not so sure about that — but they are essential to the enterprise of historical lexicography.

The masthead in Volume 1 of the Supplement lists four superstars — including the legendary reader of texts for the Supplement, Marghanita Laski — who together contributed 250,000 slips to the Supplement’s quotation files. Then, seventeen others are listed as having contributed from between 3,000 to 20,000 quotations each. This places Granville in context: he is listed as another “important” contributor, but his mail with the editors and staff of the Supplement reflects a modest contribution of something less than 3,000 quotations. Possibly, the postcards in the box represent all of Granville’s contributions, but they may represent only a subsection. Perhaps we’ll figure it out, one of these days, when someone aligns the Kripke postcards with correspondence in the archives of the Oxford University Press, evidence of the back and forth — it will be a nice piece of research.

Several excellent accounts of the Oxford English Dictionary (by Charlotte Brewer, Peter Gilliver, Lynda Mugglestone, and Elisabeth Murray) describe its reading program, including the activities of select contributors. For instance, Brewer’s Treasure-House of the Language (2007), focused on the Supplement, devotes some space to Laski, but Granville doesn’t appear in its index, and Granville’s story deserves to be told, not just for its own sake, but because he represents a large group of volunteer readers. We should learn more about him and them, and — thanks to the Kripke collection — we may be able to piece together Granville’s story, at least. His contributions (probably in the Oxford archives) and the Supplement’s responses (definitely, in the box inside the box in the Kripke Collection) give us insight into what volunteer readers do, how they do it, and why they do it. If identifying the best quotations is so important, why are all the biographies about the definers and etymologists and not the readers?

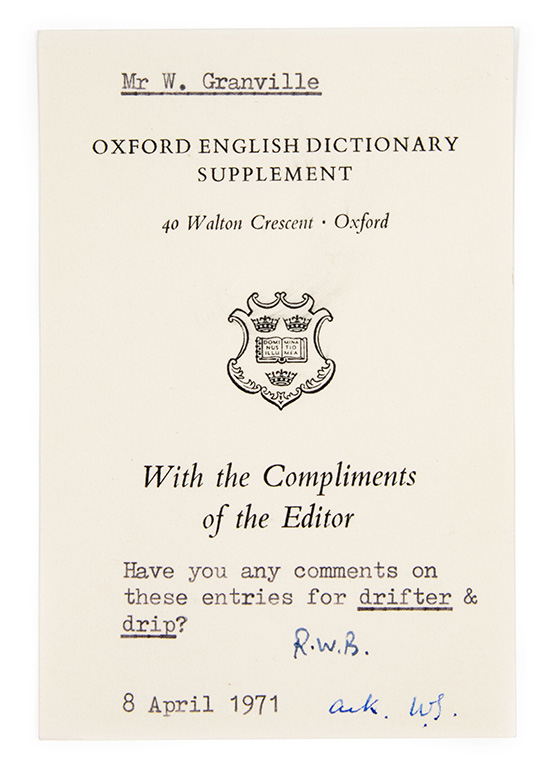

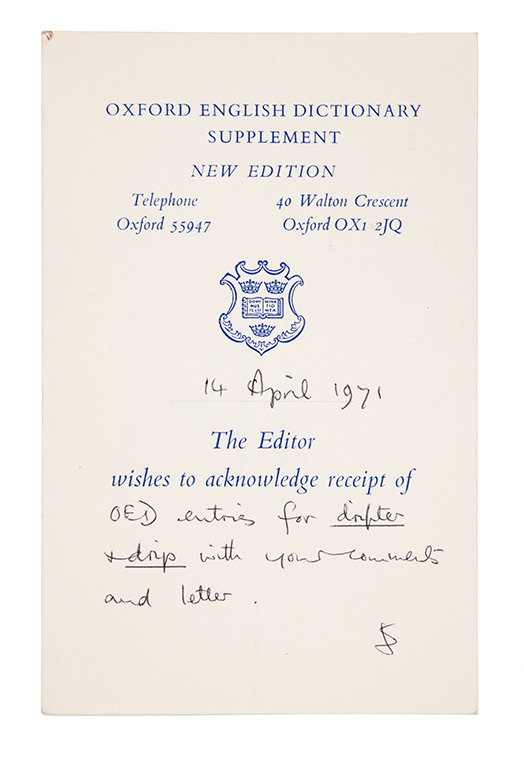

Granville supplied copious information to the Supplement editors, both quotations and commentary. The postcards indicate that he sent along data of one kind or another for bloke, drifter, drip, escort, fill in, man hours, mouldy, star, thing, and turnover, none of them quite as common as the or like, but relatively common words. This proves that Granville was a real contributor: his eyes didn’t focus only on exotic words or unexpected uses — he provided quotations for words regularly in use, in one sense or another. Historical dictionaries would be useless if volunteer contributors only sent along citations of strange words. General dictionaries are necessarily full of familiar words, though when someone looks into a dictionary, they may be made less familiar by the enriching data the dictionary supplies.

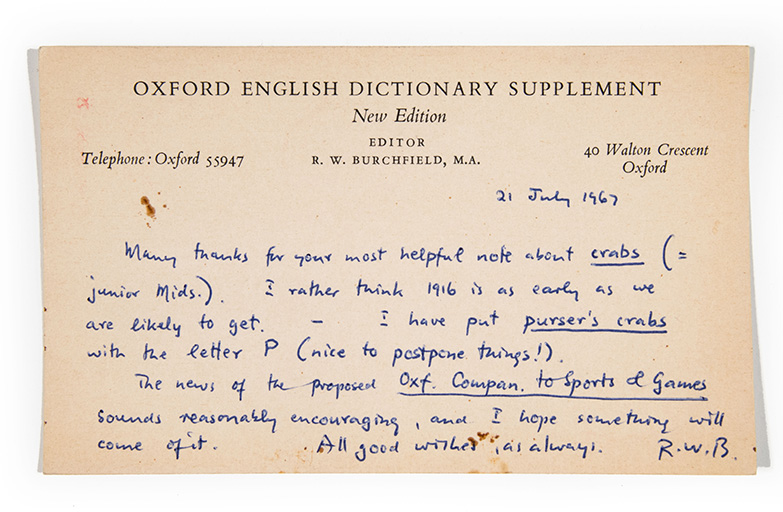

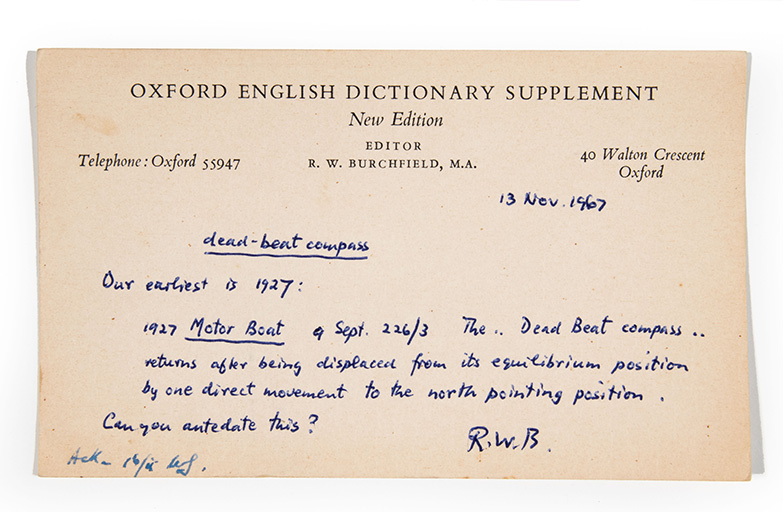

Granville also sent along evidence of rarer and more obscure words and uses, such as beef chit ‘menu’, crab ‘midshipman’, dead beat compass (too difficult to explain in a gloss), deckie ‘apprentice deck hand,’ dusty boy ‘ship’s steward’s assistant,’ as well as groups of synonyms, like cap-tally, cap ribbon, and tally ribbon — all of these, I suspect, present material found after he had finished his own dictionary of sailor slang. Also, they all appear in the Supplement, though it’s impossible to say, without looking at the material Granville sent to the editors, whether his was the evidence that counted. Then, there’s acknowledgment for evidence of tiddly-wink and the esoteric aerobate, the latter not recorded in the Supplement — no contributor bats a thousand.

Granville didn’t need an invitation to contribute to the Supplement. He initiated much of the contact. Yet Robert W. Burchfield, its chief editor, with a quotation for bull horn from C. S. Forester’s Good Shepherd (1955) in hand, asked Granville to antedate the quotation, that is, to find an earlier instance of the word. The request reveals that Burchfield relied on Granville for accurate information and ingenious reading.

Peter Gilliver writes in his magisterial The Making of the Oxford English Dictionary (2016) that the OED’s editors were “well aware of the scarcity of people qualified to contribute anything of value.” Granville was one of the élite, and so made it all the way to the masthead. Besides his own dictionaries and his contributions to the Supplement, he also contributed lexical information to Eric Partridge, editor of several dictionaries, including the Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English (1937), as I reported in an earlier post. The acknowledgments to A Dictionary of Catch Phrases (1977) introduce Granville as “an indefatigable helper.” Almost no one recognizes his name, but he was very present and reasonably significant in the dictionary world of his time. He may have had pets or other hobbies — even a family — but he absolutely lived a life in lexicography.

Leave a Reply