By Becky Craft and Brandis Malone

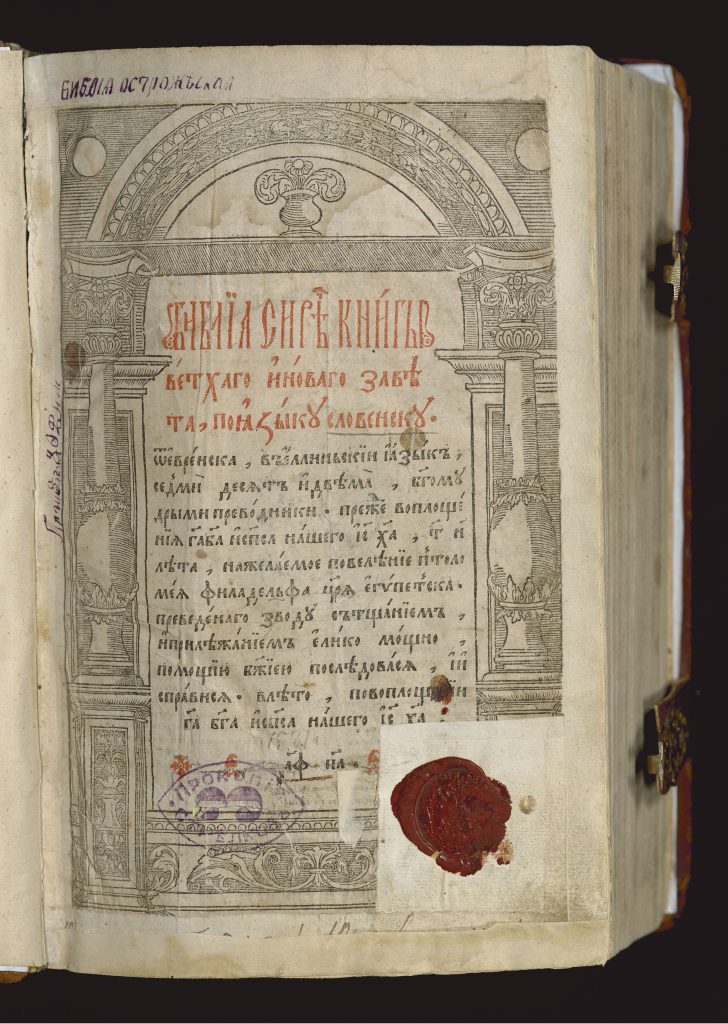

In Spring 2023, students in the History of the Book course (ILS-Z681) were tasked with an assignment to examine a book from the hand-press period printed before 1800. By chance, two of us, Becky Craft and Brandis Malone, picked the same book for our project. As fellow dual degree students in the Russian and East European Studies and Library Science program, we spent hours poring over the Ostrozhskai︠a︡ biblii︠a︡, also known as the Ostroh Bible. This large 50-line codex was commissioned by Prince Kostiantyn Vasyl Ostrozki in the late 16th century in what is modern-day Ukraine. It’s an amazing relic as it is the first Bible printed in Church Slavic with moveable metal type. Similar to the advent of the printed Bible in Western Europe during the 15th century, in Muscovy (modern-day Russia) and Ukraine, the printed Church Slavic Bible would have been revolutionary. Furthermore, the standardization and creation of Cyrillic metal moveable type would bleed into other possible areas of commerce, advancing printing in Russia and Ukraine for centuries to come. [1]

History and Printing

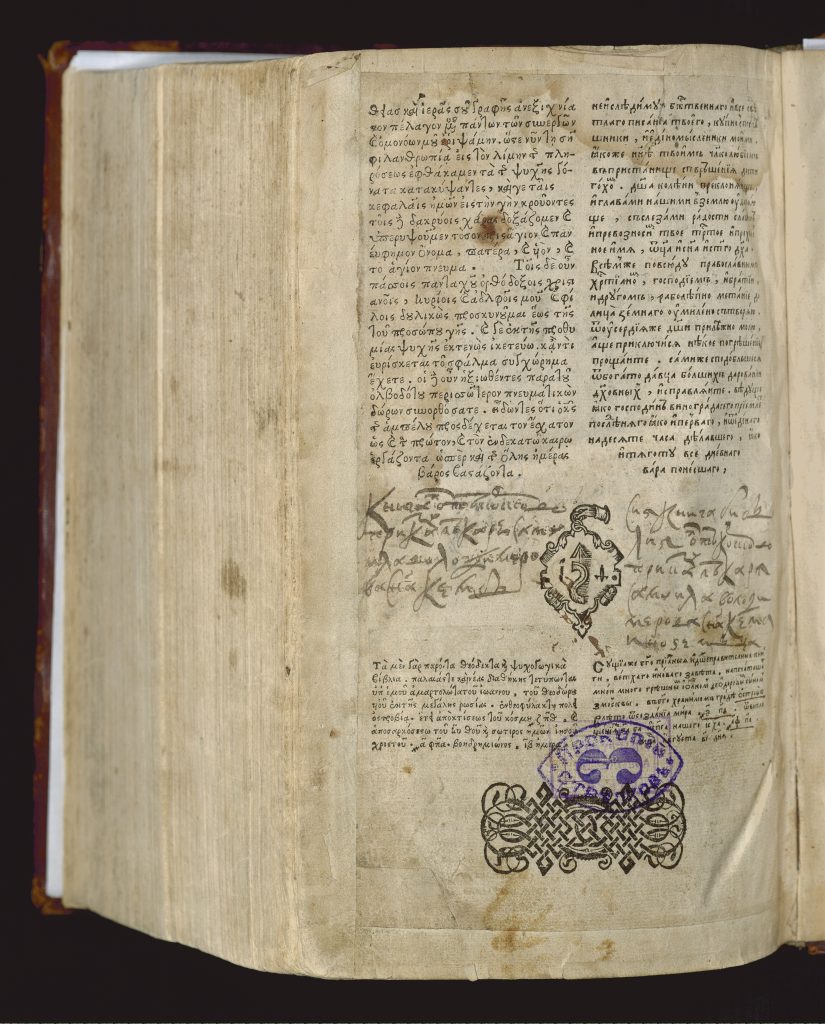

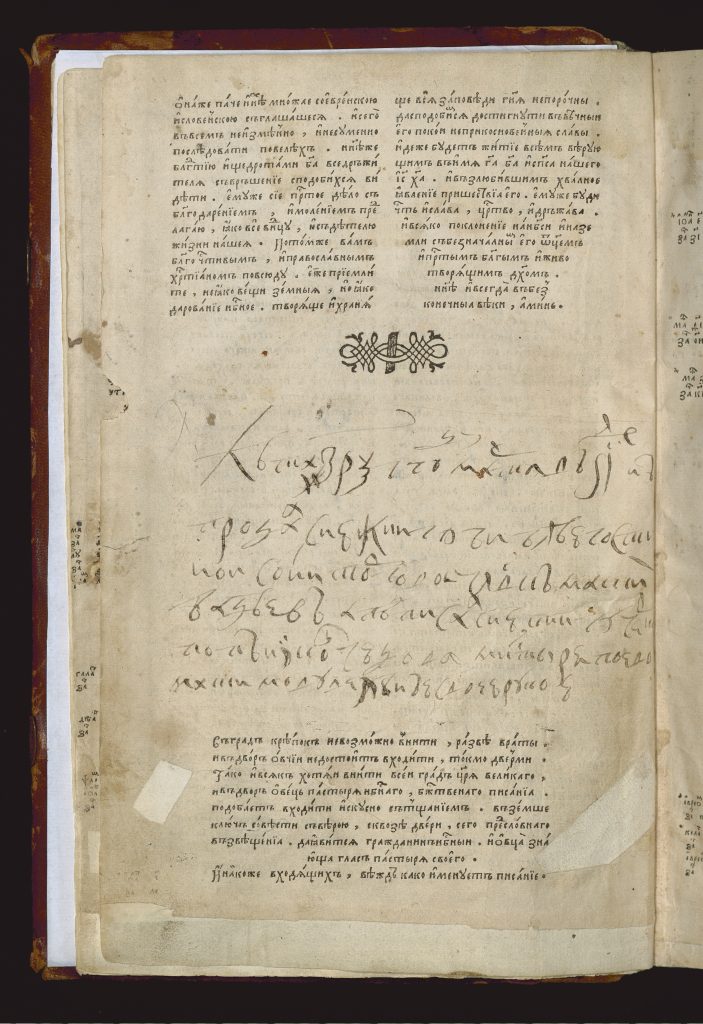

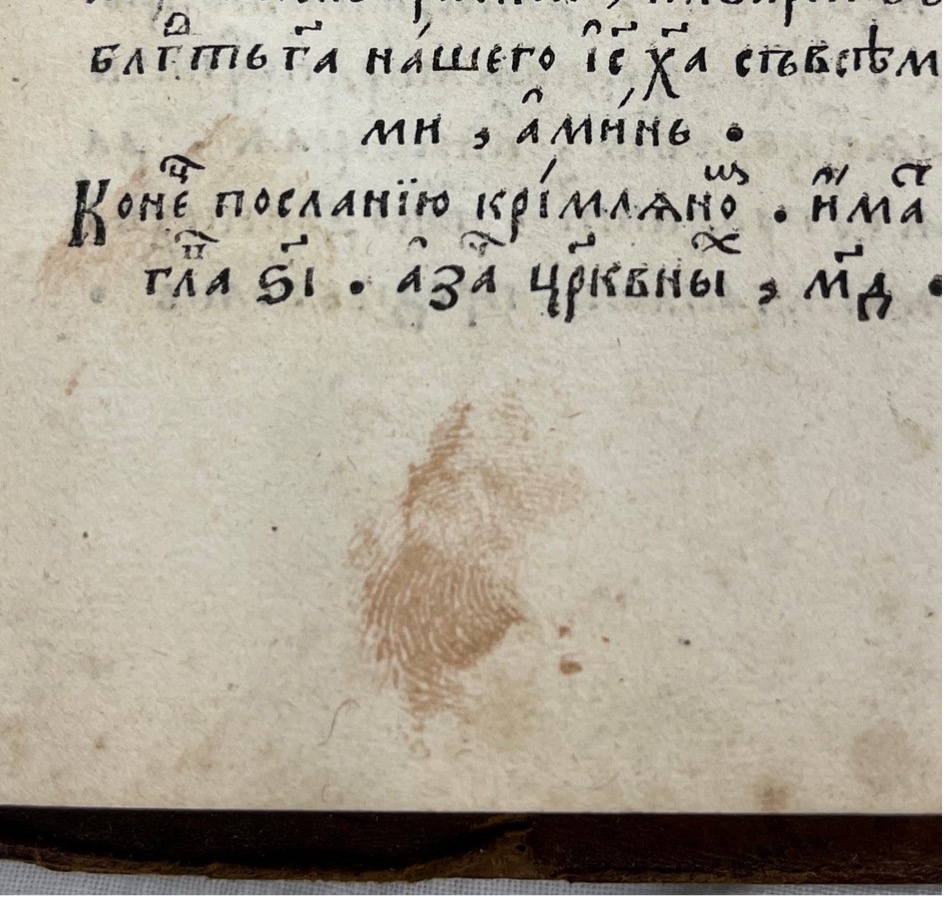

One of the most interesting aspects of this Bible is its origins. This effort was led by Ivan Fedorov, the founder of printing and publishing in Muscovy and Kyiv. He was responsible for the construction of several printing houses in the 16th century as well as the printing of many important religious and scholarly works. [2] In 1578, he founded the Ostroh Press with support from Prince Ostrozkiin Ukraine, which printed about 30 different works in its lifetime before closing in 1612. [3] The Ostroh Bible was one of the largest projects made at this printing house, completed within the first few years of opening. The Bible has numerous signs from its time at the printing press, including notes from Ivan Fedorov himself in both Greek and Church Slavic, as well as a printer’s device from the Ostroh Press.

The typeface used in the printing of the book is unique, as it is used for Cyrillic script, but it also closely resembles that of italic typefaces in the West. This might speak to Western influences on Fedorov and the Slavic printing industry as a whole during this time. Concerning the work of individual printers, you can see when the pages weren’t inked enough and where there were occasional mistakes with the casting of the type. Another bit to note here is where there is a possible bleed from the edge of the frisket, which is a metal frame used to shield certain areas on a paper from being printed when using a wooden printing press. [4] This mark is only visible on one page, but it looks like the edge was accidentally inked and pressed onto the sheet before being noticed and presumably fixed for future pages.

Watermarks

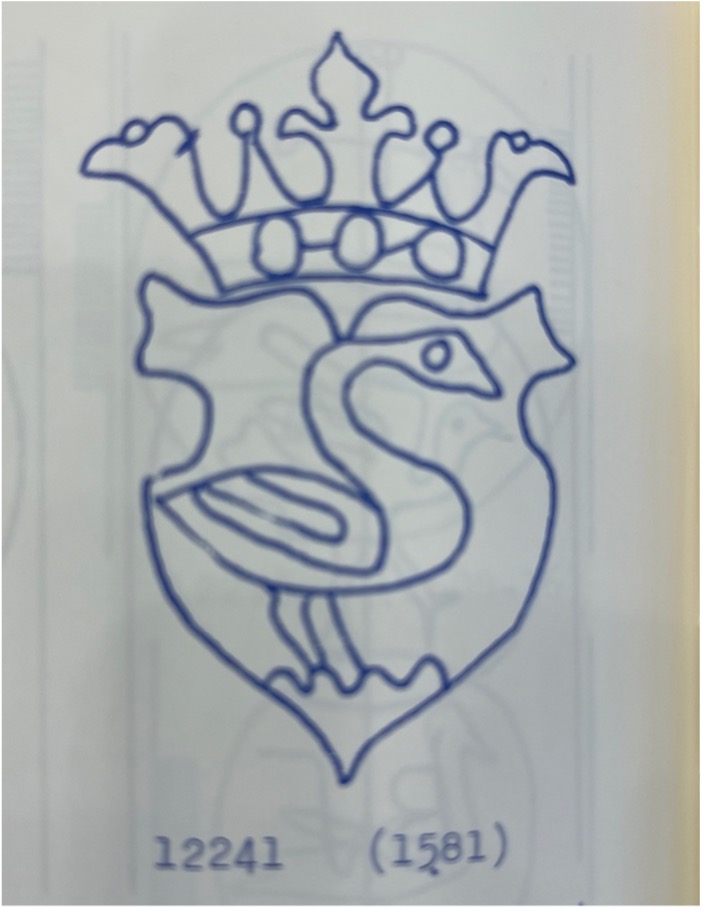

A neat fact about books made in the hand-press period is that the paper used often has hidden designs put in during production that are only visible when held up to the light. These marks can reveal a lot about where the paper was made and distributed, and because papermakers used unique designs, it’s often hard to decipher what these marks are. The Ostroh Bible is a perfect example of this, and this is where we spent most of our time examining the book. We looked through every page with a light, assigning our own names to the shapes we couldn’t make out. Our first friends were King Sheep and King Beetle, so named because they looked like those animals adorned with lovely crowns. We found other animals displayed in other watermarks – a goose and a ram. We found some less distinct watermarks that appeared as though they could be coats of arms or something similar. For others, we could only see a vague outline of their shapes – bulbs, domes, gumdrops, crowns. Trying to figure out what these watermarks were was exciting, and since we are not experts, we looked in one of the Lilly’s reference books that describes thousands of different watermarks that were used from 1282 to 1600, Les filigranes: Dictionnaire historique des marques du papier dès leur apparition vers 1282 jusqu’en 1600.

Based on our examinations of this book, we did find some close relatives, but without an exact match, it’s hard to know where and when this paper came from. All we can really tell is that there was a lot of different paper used in the production of a single copy of this book, likely ordered from multiple production houses to achieve the final product.

Users’ Marks

Something else that fascinated us during our research was the extensive users’ marks left by various readers throughout the centuries. The oldest inscriptions and notes are in Church Slavic, which appear to be written in ink that has long since faded, possibly contemporary to the text. Along with these notes are small Xs in the margins of certain passages, possibly marking where a user stopped their reading, whether for their own personal use or while reading aloud. More modern marks include names written in purple ink in the preliminaries marking ownership, as well as underlined text in a more modern red and blue pencil. Other marks were simply left throughout the years, from everyday use and by accident. Page corners are darkened by the years of hands turning the pages, along with liquid stains and drops of ink and wax appearing in various parts of the book. Many of these marks make you think more about who used this book and where, including the possible lack of lighting in rooms irrevocably influencing the use of the text.

Mystery Hair

Though there are so many compelling aspects of this object that we explored during our project, by far the one that has confused and intrigued us the most is the hair. As we were turning the pages in the book’s second half, strands of hair began to appear in the gutter, a few inches long. Becky worried that a strand of her hair might have fallen in between the pages, so she gently tugged on one of them only to find that it was firmly stuck. Each page after revealed more and more, at one point looking as if someone’s head had been shaved over the book, leaving dozens of half-inch-long strands planted in the binding. As to how and why these hairs were integrated into the book, who knows?

Conclusion

Looking carefully at books from the hand-press period provides a unique perspective into the production and printing of early books. Struggling to determine watermarks, getting excited at finding fingerprints and hair, and seeing how people have used and loved this book throughout the years was incredibly interesting. Each page truly shows how unique each copy of a handprinted book must be, both from the time it was printed and even more now, centuries later. The Ostroh Bible is one of the best examples of Slavic printing from this time period. And with its place in Slavic printing history, it allows a window into learning more about the development of printing in Ukraine, Russia, and all of Eastern Europe.

If you want to see this amazing book in person, check out the IUCAT Record to request it!

Bios

Becky Craft recently finished her master’s degrees in Russian and Eastern European Studies and Library Science in May 2023.

Brandis Malone is a second-year master’s student in the dual Russian and Eastern European studies and Library Science program at Indiana University.

[1] Raven, James, and Joran Proot. “Renaissance and Reformation.” Essay. In The Oxford Illustrated History of the Book, 137–68. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2022. 157, 163.

[2] Kubijovy, Volodymyr, and Danylo Husar Struk, eds. “Fedorovych (Fedorov), Ivan.” In Encyclopedia of Ukraine. University of Toronto Press, 1984.

[3] Kubijovy, Volodymyr, and Danylo Husar Struk, eds.“Ostroh Press.” Essay. In Encyclopedia of Ukraine. University of Toronto Press, 1993.

[4] Werner, Sarah. Studying Early Printed Books, 1450-1800: A Practical Guide. Wiley Blackwell, 2019. 17.

Leave a Reply