Any large collection of dictionaries will overflow with works by Noah Webster, but Madeline Kripke also had a collector’s eye for Websteriana. According to her incomplete catalogue, she owned at least a dozen copies of Noah Webster’s An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828). The collection also includes a miniature portrait of Webster; a silhouette portrait of Professor Chauncey A. Goodrich and Julia Francis Webster Goodrich, one of Webster’s daughters; and another miniature of Webster’s great-granddaughter, Emily Ellsworth Fowler Ford Skeel.

Madeline collected a copy of the fourth edition of Chauncey Goodrich’s Elements of Greek Grammar (1827), imposed on generations of Yale undergraduates. Goodrich was one of the sons-in-law hired by the Merriam brothers to revise Webster’s dictionary, work remembered in another of Madeline’s Webster-affiliated books, Printed but Not Published (1884), by William Chauncey Fowler, grandfather of Emily E. F. F. Skeel, who had also edited some Webster works for the Merriams. Goodrich’s nephew, Samuel M. Goodrich, under the pseudonym “Peter Parley,” compiled Peter Parley’s Bible Dictionary and Peter Parley’s Dictionary of Astronomy (both 1836) — Madeline collected those, too.

Noah Porter, another editor of G. & C. Merriam Webster dictionaries, is represented among Madeline’s dictionaries but also by George Spring Merriam’s Noah Porter: A Memorial by Friends (1893) and a copy of the Yale College Class of 1862’s yearbook. The Porters were related to the Ellsworths, and the Ellsworths were related to the Chaunceys and the Goodriches, who married into the Websters. Posthumous concern for Webster’s legacy was an extended family affair, and some of the family’s interactions with the Merriams are chronicled in an impressive nineteenth-century manuscript collection of G. & C. Merriam correspondence and business records, one of Madeline’s prize acquisitions.

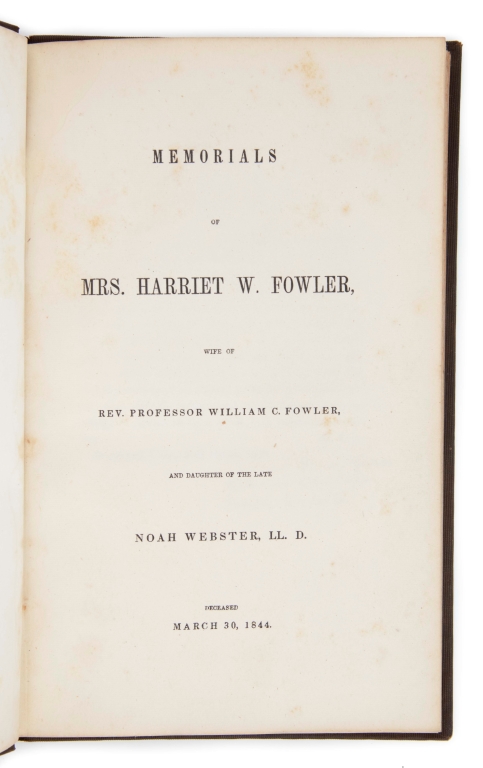

These items are dispersed among the 1500 and more boxes of Kripke material in the Lilly Library. Add to them a nicely bound, crisp copy of a slim but serious volume, titled

Memorials of Mrs. Harriet W. Fowler

wife of

Rev. Professor William C. Fowler

and daughter of the late

Noah Webster, LL.D.

Deceased

March 30, 1844.

and explained thus by yet another of Webster’s sons-in-law, Harry Jones:

In arranging for the press these memorials of the late Mrs. Fowler, reference has been had solely to the circle of her relatives and friends. And it has been deemed advisable to leave them mainly in their original state, lest an attempt at greater unity might diminish something of their freshness and feeling. The funeral address, the obituary notices, the letters of her friends, the record of early religious experiences, by her own hand, and even the journal of her last illness, penned amid fast falling tears, and conveying the broken utterances of an afflicted husband’s grief, appear as they were originally written; and any attempt essentially to abridge or reconstruct them, would have seemed like sacrilege.

The Reverend Herman Humphrey, D.D., President of Amherst College, gave the funeral address included in the book, and whoever wrote the obituary that appeared in The Boston Recorder was deeply affected by Harriet Fowler’s passing:

There is something beautiful and fragrant, beyond expression, in a life and death like hers whom we have so lately carried to the grave. That both may prove, through their abiding remembrance of them, a refreshment and a solace to the hearts now aching in silence beneath this severely bereaving providence of God, is the prayer of one who begs permission to weep in this deepest anguish of their lives.

A bit prosy and beyond grammar, perhaps, but expressive. Harriet Fowler’s father earned many an encomium, as one expects a founder of the Republic and original lexicographer would, but nothing so lovingly disordered as this obituary.

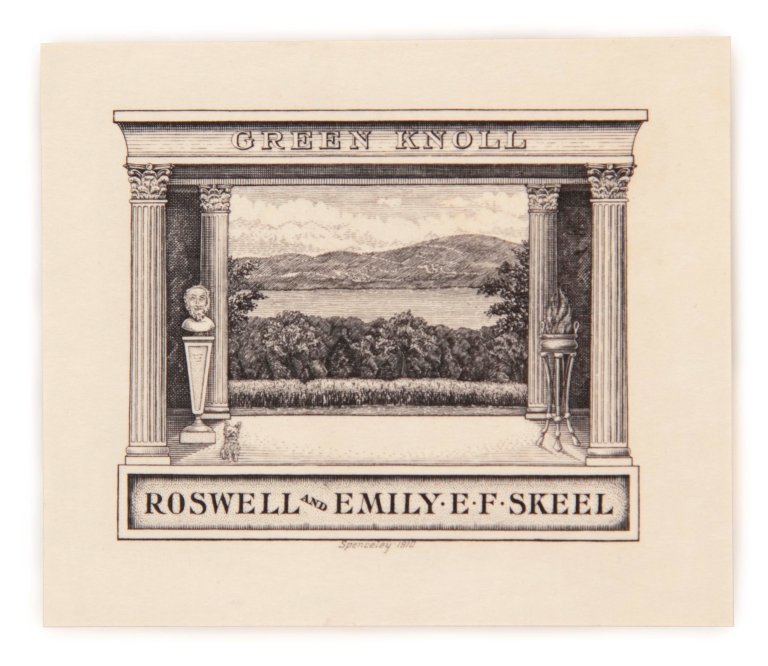

Emily Skeel, Harriet Fowler’s granddaughter, edited two important works about her great-grandfather, her mother’s two-volume Notes on the Life of Noah Webster (1912) and her own Bibliography of Noah Webster’s Writings (1958) both of them in Madeline’s collection, the latter referred to many times in the short catalogue’s entries for other works. Until it acquired Madeline’s collection, the Lilly Library held neither of these books, nor had it owned a copy of the Memorials of Mrs. Harriet W. Fowler. Perhaps even more exciting, Madeline’s was no mere copy of the Memorials. It was, in fact, Emily Skeel’s copy, as attested by a bookplate naming her and her husband Roswell Skeel, with a picture of their home, called Green Knoll. In auction catalogues, books with this plate are considered “very scarce.”

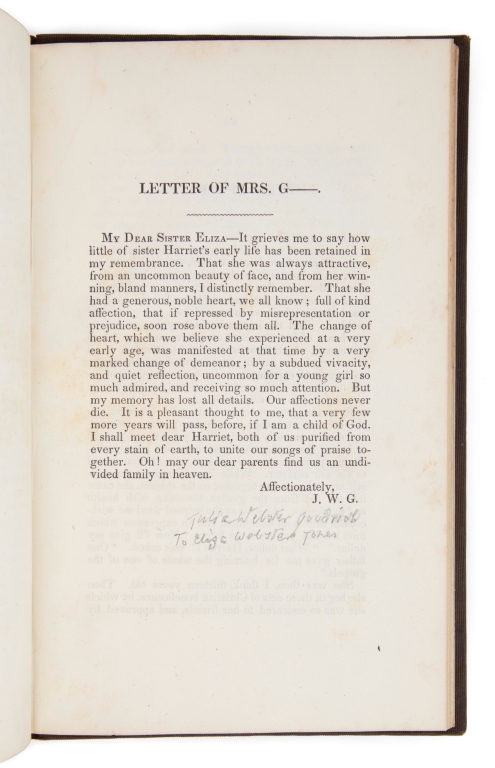

The most precious features of the book are the marginalia. Below the preface, Harry Jones signed himself “H. J.,” but we know his specific identity from a penciled annotation, “son-in-law of Noah Webster.” Among the correspondence that makes up a few of the book’s pages, the annotator deciphers “J. W. G.” as “Julia Webster Goodrich to Eliza Webster Jones,” while, for instance, other correspondents are identified as “Mrs. Emily (Scholten) Webster Fowler to Mrs. Harriet Webster (Cobb) Fowler” and “Mrs. Rebecca V. Greenleaf Webster [Noah’s wife] to her daughter Eliza Webster Jones.” The specificity of the annotations suggests inside knowledge, unsurprising in a family copy of a book celebrating a member of that family.

But who wrote the annotations? Perhaps Emily Fowler Ford, Emily Fowler Skeel’s mother, deciphered the initials and otherwise annotated her own copy of the Memoirs — surely, she had one — on the way to assembling her Notes. Indeed, knowing, as she probably did at some point, that she wouldn’t see the Notes through to publication, she annotated the Memoirs to assist Emily Skeel’s editing of them. Or, perhaps Emily Skeel, conversant as she was in family history, annotated this copy of the Memoirs when she inherited it, to alleviate posterity’s confusion. Obviously, settling the question requires expertise in various Webster clan cursive hands, but I — and I hope not I alone — am excited at the prospect of solving this and similar bibliographical mysteries. One annotation, bookplate, inscription at a time, and we can improve our understanding of American cultural history by means of the history of lexicography.

Leave a Reply