Greater awareness has risen recently concerning the phenomenon of “Poison Books”: that is, books containing pigments composed of heavy metals that are known to be hazardous to human health. Mercury, lead, chromium and arsenic-based pigments are generally the elements known to be present in bindings-they’re used to color the book-covering cloth, leather and/or paper- chiefly within the 19th century (largely the 1840’s-1860’s), and most likely of European or American publishing origin.

Background

Doug Sanders, Paper Conservator within the Preservation Department at Indiana University Libraries, is actively working towards identification and policy development concerning this issue. Heavy metals have been known since antiquity to have toxic effects, but it wasn’t until the 1860s that formalized health research began in earnest. We now know that long term exposure can lead to various carcinogenic, nervous system, and circulatory effects and that there are effective treatments. There’s now an international group of conservators (myself included!), librarians, industrial hygienists and conservation scientists drafting a policy paper to better inform our colleagues about the issues.

Two specific pigments that are the current focus of much work within libraries are Scheele’s green and Emerald green, both copper-arsenic containing compounds. Both are quite enigmatic colors and likely were received with great interest when they hit the bookbinding scene in the mid-1800’s. A simulated color of emerald green fills the top of this blog post. These colors however, had a relatively short life- only a matter of a few decades- before the dangers were known and they faded from use. Interestingly, Emerald green still continued to see use as a rat poison, often under the pseudonym Paris green. As of February 2023, there are 146 known titles which have been verified to contain this pigment. Pigments containing heavy metals are also present in maps, paintings, medieval illuminated manuscripts and other artifacts of our collective cultural heritage

How do we identify these pigments?

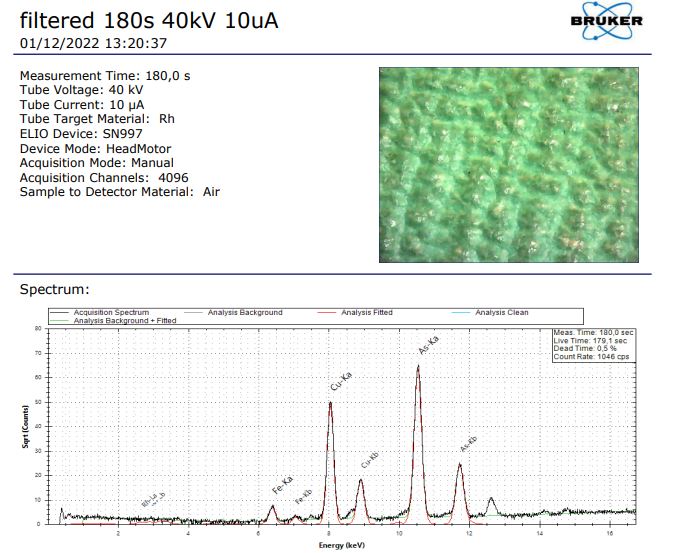

There are several methods available to help obtain a positive identification. Microscopy, Raman laser spectroscopy and chemical reagent spot tests are all methods which can be used and are generally known to a conservator. XRF (X-ray fluorescence) spectroscopy is the method I’ll be using however. XRF gives a quick, non-destructive and largely unequivocal result.

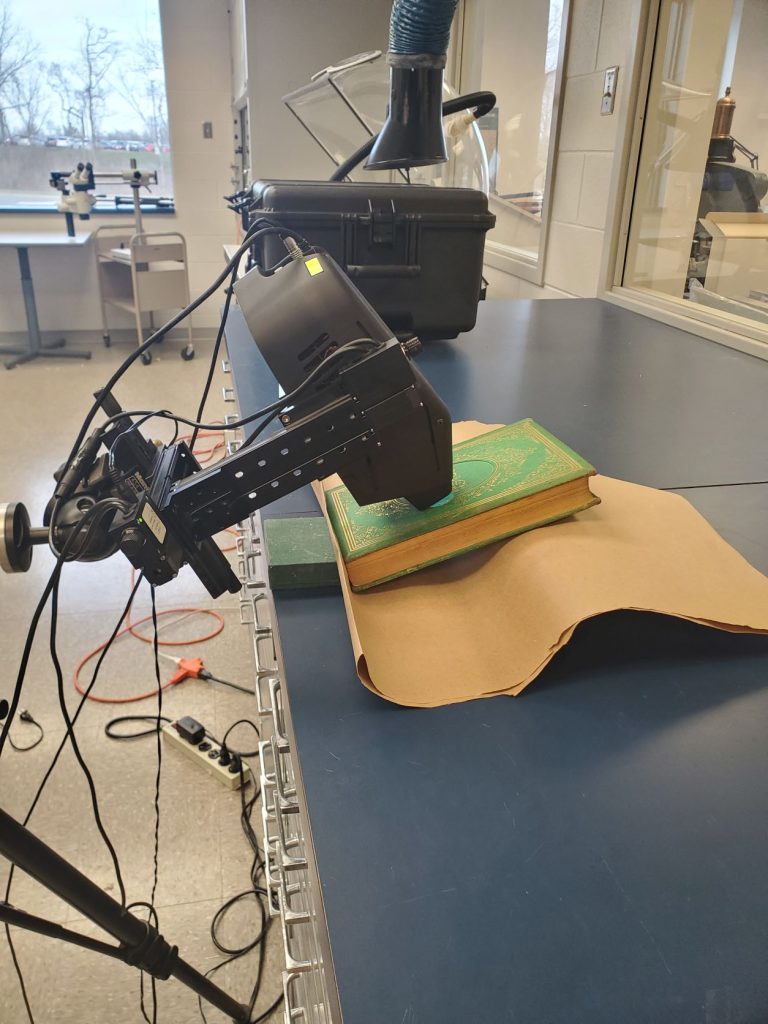

Here, we see a portable XRF instrument taking a reading from a book within the Lilly Library collections suspected and now proven to contain emerald green pigment.

This is the XRF spectrum from the tested book. It shows the copper (Cu) and arsenic (As) peaks associated with emerald green and gives confirmation of a copper-arsenic containing compound.

I’m working with colleagues in the Lilly Library Technical Services department, Lindsay Weaver and Kori Newboles, to sort through their collections catalog and generate a list of likely candidates to begin testing. We’re beginning with the global list at the Arsenical Books Database and then expanding to encompass other books by known publishers who used emerald green, other books cataloged as having green bindings, and books within the dates of known use. Once that is done (we have a tentative list of ~114 right now!), we’ll establish a workflow to test for chemical presence and suitability for future access based on condition.

Where to from here?

Additionally, I’ll be working to establish storage, retrieval and handling procedures so that staff and patrons can hopefully still access these reading materials safely, with much reduced risk to health. The threat is chiefly from ingestion (rather than inhalation) if the book is in good condition. Procedures will likely include gloved handling, washing afterwards and limiting direct contact between book and reading room furniture, shelving carts etc. In short, we can still appreciate the books but with some common sense risk reduction and care. The project will likely expand to other collections and libraries within the IU Libraries system. It’s important to keep in mind that health hazards are all around us and we learn to mitigate these daily through smart risk management approaches. Interestingly, natural history museums and archaeological collections have dealt with toxins (usually in the form of old pesticide applications) in their collections for many years and have much to share with us in terms of policy development.

I find the origin and development of pigments and their use in library and archival collections a fascinating topic. This is just one aspect of a larger story continuing to play out within our stacks.

Leave a Reply