Madeline Kripke favored profanity and obscenity and collected many works published during the Great Censorship, when the Comstock Act of 1873 deprived Americans of James Joyce’s Ulysses and D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover and a host of other titles people recognize less easily, including Allen Walker Read’s Lexical Evidence from Folk Epigraphy of the Western United States and Canada (1935) — well-represented in the Kripke Collection — published in just seventy-five copies at the Obelisk Press in Paris, then smuggled into the United States. Who knew that scholarship could be so risky and exciting! Madeline also collected so-called Tijuana Bibles, pornographic comics bravely produced in the United States despite Comstock. This is just to say, she disagreed with censorship, with hiding knowledge of language in the world behind propriety.

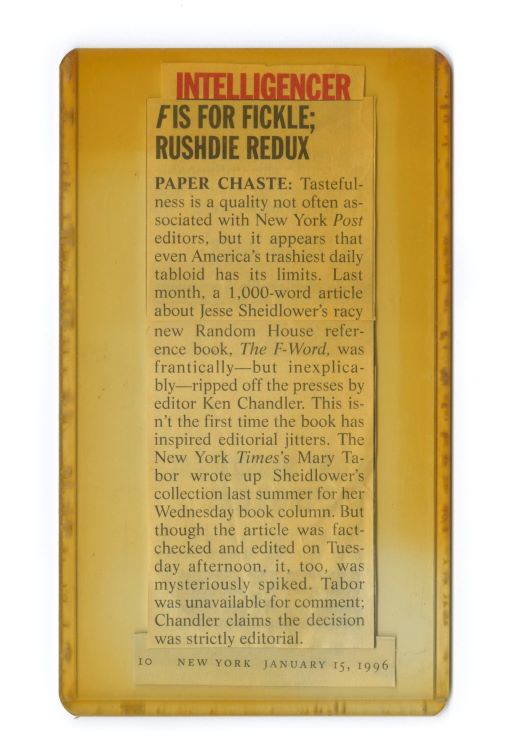

Perhaps the smallest (shortest, thinnest?) item in the collection is a clipping from New York magazine’s Intelligencer, dated January 15, 1996, about alleged censorship in notices of Jesse Sheidlower’s specialized dictionary The F-Word, published by Random House in the previous year. The clipping is inserted into a hard plastic, column-sized sleeve and had fallen into a crevice among books in a box of Kripke materials, as though it were an afterthought, but the care with which Madeline preserved it suggests otherwise. Sheidlower, once a lexicographer at Random House, then Editor-at-Large of the Oxford English Dictionary, and now editor of the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction (https://sfdictionary.com/), was a friend of Madeline’s, and she collected copies of the 1995 and 1999 editions inscribed and presented to her by Sheidlower, as well as the third edition of 2009.

You can imagine the size of the clipping and the sleeve from the length of the article inserted therein, quoted here in its entirety:

F is for Fickle; Rushdie Redux

Paper Chaste: Tastefulness is a quality not often associated with New York Post editors, but it appears that even America’s trashiest daily tabloid has its limits. Last month, a 1,000-word article about Jesse Sheidlower’s racy new Random House reference book, The F-Word, was frantically — but inexplicably — ripped off the presses by editor Ken Chandler. This isn’t the first time the book had inspired editorial jitters. The New York Times’ Mary Tabor wrote up Sheidlower’s collection last summer for her Wednesday book column. But though the article was fact-checked and edited on Tuesday afternoon, it, too, was mysteriously spiked. Tabor was unavailable for comment; Chandler claims the decision was strictly editorial.

The spiked articles need not even have used the actual F-word, deploying the F-word euphemism instead, so it’s hard to understand why sophisticated publications would make such strictly editorial decisions. Perhaps the editors disapproved of profanity or books about profanity; or they feared letters from angry readers dead set against any sympathetic approach to profanity; or publishers, eyes on the bottom line, wanted to avoid public disapproval. They bowed to pressure, real or imagined.

In the first edition, Sheidlower wrote, “Today, it seems that the taboos against the F-Word are weaker than ever. While a few publications (The New York Times, for one) still refuse to print [the F-word — see how easy that was?] regardless of the circumstances, the word can be found quite easily in most places.” After 1996, however, and the Intelligencer note, which he read as surely as did Madeline Kripke, Sheidlower expanded his treatment of F-word censorship, with a section titled “[F-word] in Print,” in which he points out that since 1995, nearly all leading newspapers and magazines — including The New Yorker and The New York Times — had capitulated in the face of everyday usage, because they found it increasingly difficult to quote sweary people without reproducing their F-words in print.

Madeline preserved the clipping because she knew Sheidlower well. She collected clippings of interviews with him and other articles about his career as a lexicographer, too. Personal relationships often motivated her collecting, as we’ve seen in posts about other items from her collection. However, she was also impatient with squeamishness about sexuality and sexual language and aware that the F-word serves English well beyond its sexual meanings, so not inclined to approve the censorship surrounding publication of Sheidlower’s book. Still, she would have found the episode humorous. It’s delicious, isn’t it, to read journalists disclose the — arguably trivial — censorship exercised by editors supposedly guarding the integrity of their publications, but really avoiding negative public reaction by declaring some of the news unfit to print. Actually, though, it’s not trivial — censorship is never trivial — and the clipping in its plastic sleeve is a talismanic reminder of that fact.

Despite editorial timidity on publication of the first edition, Sheidlower remains undaunted. He recently announced that he’s preparing a fourth edition of the F-Word on the blog Strong Language: A Sweary Blog about Swearing — https://stronglang.wordpress.com/2023/03/ 22/help-revise-the-f-word/ — and elsewhere. That is, both the F-Word and the F-word win the argument — the censors deservedly lose. They lose in the sense that Madeline’s preserved copy of that clipping exposes them. We think, not unreasonably, that the bad decisions we make will somehow be lost to history, but collectors like Madeline preserve traces of bad judgment and their archives set the record straight in perpetuity. In this case, we witness the persistent censorship of profanity and works that discuss profanity almost to the end of the twentieth century, which is not finally about this or that editorial decision but about how those decisions reflect American culture of the time.

When the fourth edition of The F-Word is released, I’ll make sure the Lilly Library receives a copy, perhaps inscribed in Madeline’s memory by the author. Of course, it won’t be in the Kripke Collection, not officially, but had Madeline survived to see its publication, it surely would have been. In an era when more and more books are banned and some probably burnt and dumped on the ash-heap of the history of censorship, it’s good to know that Madeline’s sharp eye and acquisitive impulses created an irrefutable archive, not only of strong language but our reactions to it.

Leave a Reply