By Travis Whaley

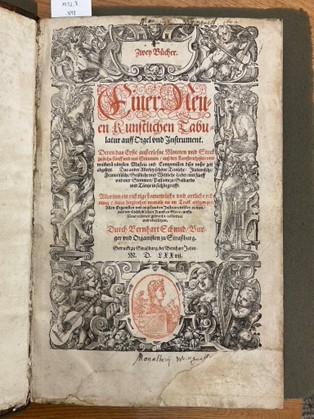

This summer, the Lilly Library acquired a rare copy of Bernhard Schmid’s Einer neuen kunstlichen Tabulatur auff Orgel und Instrument, published in 1577 in Straßburg. This is the only copy of Schmid’s Tabulatur in the United States; the other three known surviving copies are in Basel, Switzerland; Munich, Germany; and Cologne, Germany.

The title translates to “A New, Artful Tablature for Organ and Instrument.” It is a collection of sacred and secular compositions for keyboard written in so-called organ tablature. Schmid’s Tabulatur is one of only nine organ tablature collections published in Germany, all appearing between the years 1571 and 1617. Among these nine organ tablature collections, Schmid’s stands out due to the range of musical genres he includes, from choral works to stylized dances. Its importance to the study of renaissance keyboard music cannot be overstated; it shows the breadth of music performed in church and played in the home on keyboard instruments during the early seventeenth century, all collected in one document.

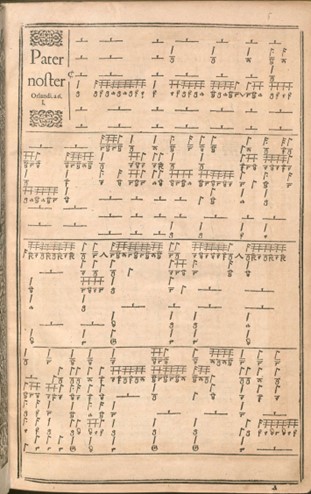

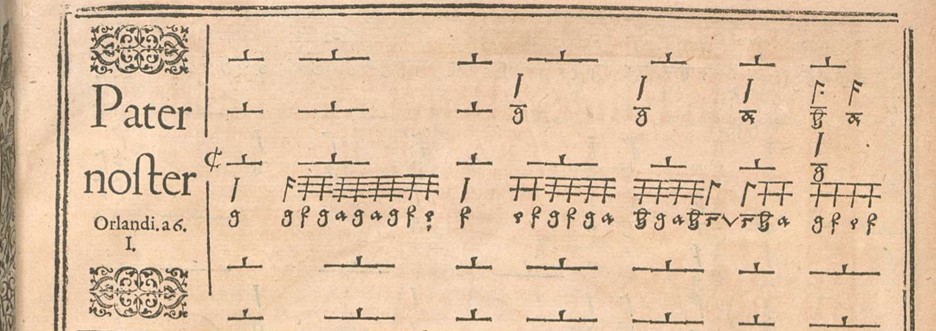

Here is the first piece in Schmid’s collection, “Pater Noster” by Orlando Lassus. At first glance, this looks like a string of letters and squiggles rather than music. It may not look like it, but this is keyboard music, like Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata” or Debussy’s “Claire de Lune.” The notation system – “organ tablature” – was used by musicians in German-speaking areas from the fifteenth to the eighteenth century. Even though this system is called “organ” tablature, musicians used it to play any keyboard instrument, including the harpsichord or clavichord, in addition to the organ.

Organ tablature uses the letters A through H to indicate the keys of the keyboard, rather than notes on a 5-line staff to show pitches. The music is written as individual “voices” stacked on top of each other, each read across simultaneously, rather than condensed on two staves as is customary for keyboard music today. Organ tablature works by telling a musician exactly where and when to put their fingers on the keyboard; it is a map for the organist’s body. This is in contrast to today’s notation, where the up and down of notes on a staff mimics the metaphorical height of high notes and the depth of low ones.

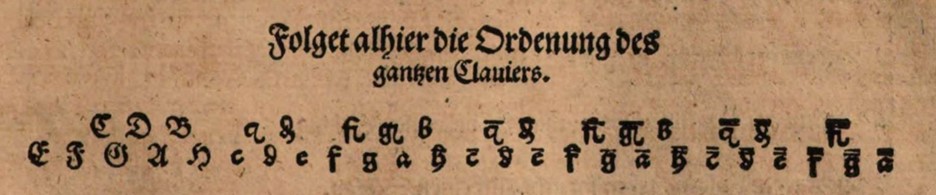

The first publication to use this version of organ tablature was Elias Ammerbach’s Orgel oder Instrument Tabulatur, published in 1571. In the preface, he provides a tutorial of the notation system. Here is his diagram of the letters laid out in the pattern of a keyboard (white keys on the bottom row and black keys on the top row, in their familiar groups alternating twos and threes):

Each letter of the alphabet is written in the place of a specific key. For example, the letter “e” corresponds to the “e” key on the keyboard. The keyboard contains more than one note called “e,” though, meaning the letters must repeat. We need a bit more information to know exactly to which “e” key the letter “e” corresponds. That’s where the horizontal lines and capitalization come in. On Ammerbach’s keyboard (above), the letters for the lowest octave (cycle of eight notes–A through G and starting on A again), on the left side of the diagram, are capitalized. When the letters restart with “c” for the next octave, they are lowercase. For the octave above that, they are lowercase with one horizontal line above them. Finally, the highest octave of the keyboard uses lowercase letters with two horizontal lines above each. The horizontal lines and capitalization tell an organist exactly where on the keyboard they should put their fingers.

Here is the first line of Schmid’s collection, the opening of the “Pater Noster” (seen above), transcribed and condensed in staff notation. The first letters of the tablature are: g g f g a g a g f e f. The symbols above the letters show the rhythm.

The first half of Schmid’s collection contains vocal pieces arranged for performance on a keyboard. All the pieces in this publication are “colored,” meaning that Schmid has embellished the source material with “coloratura” (colorations) and ornamentations. In the preface, he explains his decision to alter the material:

Thus I have adorned the motets and pieces, which are incorporated in the whole work, with a little coloration, not with the intention of binding knowledgeable organists to my colorations, but to leave each one free to his improvement, and only as mentioned, [the coloraturas are] provided for the sake of budding instrumentalists, although I myself would have preferred that the composer’s authority and art remain unchanged.

Schmid provides his own embellishments but clarifies that an organist should not feel bound to them. In fact, he prefers that the original composer’s authority remain unchanged.

If that is truly the case, why does he alter the music? He intends his colorings to be a guide for beginning instrumentalists to follow. For “knowledgeable” organists who already know how to improvise, he encourages them to improve upon his suggested embellishments. The pieces printed in this collection thus represent only one possibility of performance. It was up to the musician to make the pieces their own in performance.

According to the inscription on the cover, the Weingarten Abbey (“Monasterii Weingarth”) acquired this copy in 1600 under the direction of Jacob Reiner.

Reiner served as the Kapellmeister (music director) at Weingarten from 1575-1606. In the year before he arrived at the Abbey, he studied in Munich with Orlando Lasso, one of the most prominent composers of the 16th century. Lasso was an Italian musician who traveled widely, spent the latter half of his life in southern Germany, and synthesized musical styles from all over Europe in his compositions. It is no surprise that Reiner would have been interested in a Tablature that included so many of his former teacher’s compositions.

Travis Whaley is a PhD candidate in Musicology at the Jacobs School of Music and an organist. His dissertation, Organ Tablature and Conceptions of Music in the Seventeenth Century, explores notation as a tool with musical consequences and how different notation systems affect all aspects of music making.

Leave a Reply