If you supply schools with dictionaries and hope that every home with children will have a children’s dictionary handy, you must convince the children in question to use those dictionaries wisely. In a previous post, I introduced some dictionary exercise books meant to enhance dictionary literacy in classrooms. Those workbooks supported the Merriam-Webster dictionary program. One of Merriam-Webster’s rivals in that market, Scott, Foresman of Chicago, was especially smart about its marketing to children, from the Dick and Jane readers to the Thorndike-Century dictionaries. Clarence L. Barnhart was the editorial genius behind that line, which eventually was renamed the Thorndike-Barnhart dictionaries, and he had marketing smarts, too. He needed them. For most of his career, he ran a very successful freelance lexicography operation. Besides the Kripke Collection, the Lilly Library holds nine tons of unprocessed Barnhart materials.

A little bit of Barnhart will make it into the library’s catalogue sooner than that mass of records. The Kripke Collection probably includes Thorndike-Century and Thorndike-Barnhart dictionaries, though Madeline’s incomplete catalogue doesn’t list them. But I didn’t expect to find, between books in one of the boxes I opened the other day, a card game designed to introduce young students to English vocabulary and to market the Thorndike-Century Junior Dictionary. The game is called Say the Word: A New Game for Children Based on the Thorndike-Century Junior Dictionary, so the deck’s dual purpose couldn’t be clearer. The extant catalogue proves that Madeline collected at least two other interesting promotional items for the Thorndike-Barnhart dictionaries. One of these, from sometime in the 1950s, is titled “Tim Makes a Friend: A Dictionary Play for Grades 4–8 […] Spotlighting the Kinds of Help Children Can Get from A Dictionary and Dramatizing Some Important Dictionary Skills,” just six-pages long, and I can’t wait to read it. The second, from c1965 and extending to twenty-four pages, is titled “What Goes into a Dictionary: A Young Person’s View of Dictionary Making,” and it appears to address the perennial question of how lexicographers develop wordlists for their dictionaries. Say the Word, however, does not appear in the partial catalogue of Madeline’s collection.

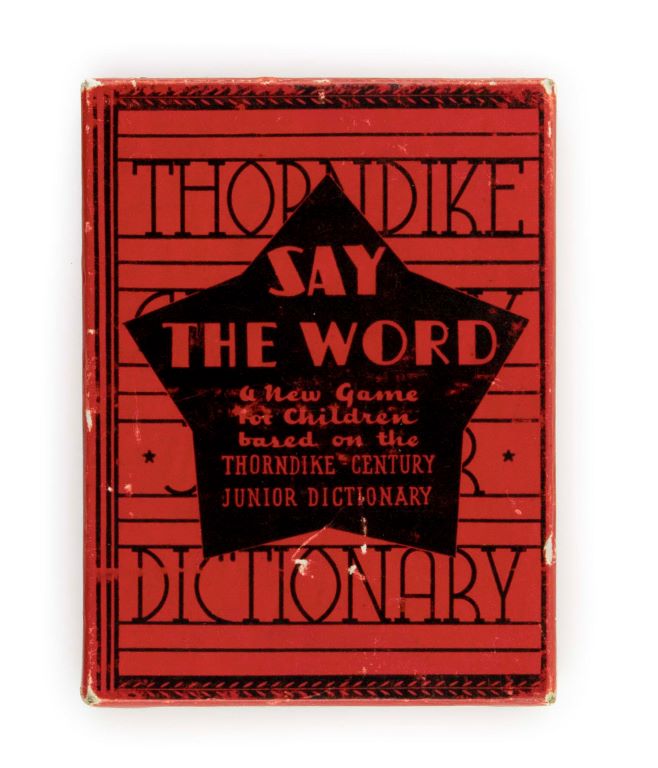

Say the Word packs fifty cards into a red box with black lettering and design. The background is partially covered by a star on which the title is inscribed. The cards, stacked in two piles, are made of thick cardboard, not the glossy thin cards one finds in a pack of modern playing cards. Say the Word is not an especially imaginative game: one child acts as the “teacher,” who shuffles and deals the cards in equal portions to all the players. Each card presents a player with a definition followed by a sample sentence with the key word left blank. The player is supposed to supply the word that corresponds to the definition, thus filling in the blank. A player who fails to match definition and word passes the card to the player on the left. Cards answered correctly accumulate in a pile, and the player with the most cards at the end of the game wins. With so few cards in the deck, the game is easily exhausted and thus perhaps perfectly suited to the shifting attention of fifth and sixth graders.

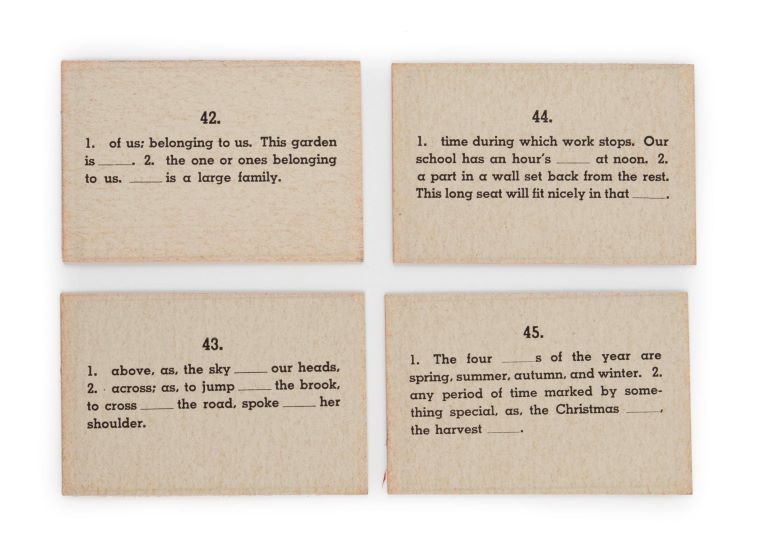

So, for example, Card #44 reads as follows:

1. time during which work stops. Our school has an hour’s _______ at noon.

2. a part in a wall set back from the rest. This long seat will fit nicely in that _______.

Along with the cards, the box includes a folded insert, package rather than pile-sized, six pages long, starting with “How to Play SAY THE WORD,” and ending with all of the answers. If you haven’t figured it out already (or simply delight in confirmation), the answer to Card #44 is “recess,” which my son, when he was of the game’s target age, always listed, along with lunch, as his favorite period in the school day. Scott, Foresman knew the audience for its children’s dictionaries.

I said before that the game’s purpose couldn’t be clearer than presented in the box and the cards, but the insert includes an advertisement, according to which the game will “teach the meanings of words to children,” but beneath that perfectly responsible pedagogical objective, we encounter

THE THORNDIKE-CENTURY

JUNIOR DICTIONARY

By E. L. Thorndike

Teachers College, Columbia University

[star symbol]

From every point of view a child’s book!

23,281 words 1610 pictures

970 pages $1.32 list

[star symbol]

Scott, Foresman & Company

Chicago Atlanta Dallas New York

The star symbols in this advertisement pick up the star motif represented on the front of the box, which is tight visual marketing for the time. The number of pages and entries might seem excessive in a dictionary for children at first glance, but the Thorndike-Barnhart High School Dictionary (Third edition, 1962), revised from the Thorndike-Century Senior Dictionary (1941), is yet longer at 1,096 pages and enters over 75,000 words. Appropriately, the Junior Dictionary includes more pictures. My favorite detail is the price: in what instance today is 30¢ a price determiner, let alone the last two cents of the list price for the Thorndike-Century Junior Dictionary?

Say the Word is not currently available for sale or even present on the Web, which underscores a point about Madeline’s curation and the importance of collections like hers. Yes, the collection includes rare dictionaries that serve as milestones in the progress of lexicography, and such books are important and expected in a collection like hers. But the collection also includes priceless items, priceless because they’re missing from view — no one knows about them, so they have no market value. They are ephemera, easily lost in attics and the backs of drawers, easily tossed in a bin when decluttering the house. Some items in Madeline’s collection, perhaps this one, as well as the dictionary play and “What Goes into a Dictionary,” may eventually be the only surviving examples of those items, so Madeline’s thoughtful collecting will have saved us from many an ignorance.

1 Comment

I love seeing this stuff.

I’m the happy owner of a 1928 G. & C. Merriam pamphlet for children, The Value of the Dictionary, with lessons about alphabetical order, finding words, the parts of a dictionary entry, the parts of a dictionary. It begins: “What is this book? It is the dictionary. It is a storehouse of information. Do you know how to use it? ‘No,’ you reply.”

Maybe there’s a copy in the Kripke collection.