We hoard our slang in dictionaries, but lexicographers, like the dragons of lore, steal their gems from others. In the nineteenth-century, people interested in such uncut words looked for them in popular song, some of which was too coarse to print, except privately. Two dragons, John S. Farmer, who with W. E. Henley (they came up in a previous post), compiled the game-changing Slang and Its Analogues, in seven volumes (1890–1904), which Madeline Kripke acquired for her collection, of course. Farmer, especially, plundered lexical baubles from bawdy ballads to shine and sparkle from the heap of slang therein contained.

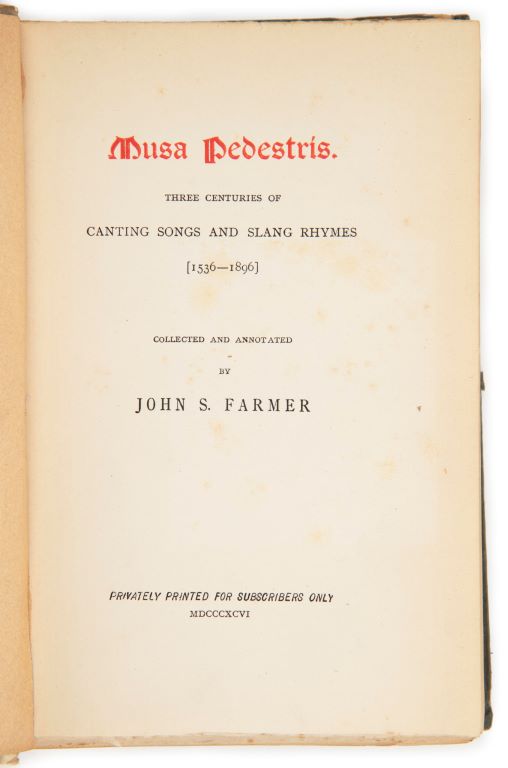

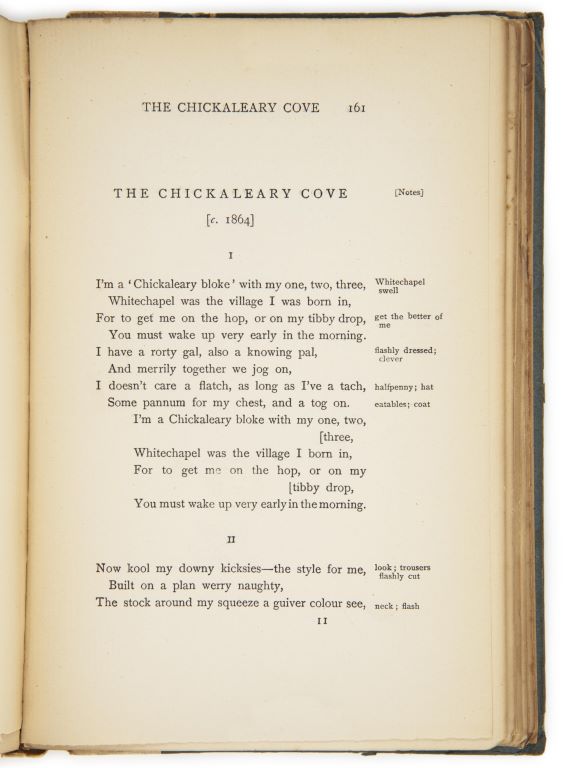

Farmer collected lots of material in advance of the big dictionary, publishing some of it concurrently, such as Musa Pedestris: Three Centuries of Canting Songs and Slang Rhymes 1536–1896, published privately in that last year. Some of the contents capture Cockney slang and sentiments, for instance, “The Chickaleary Cove,” which Farmer dates as “c.1864”:

I’m a “Chickaleary bloke” with my one, two, three,

Whitechapel was the village I was born in.

For to get me on the hop, or on my tibby drop,

You must wake up very early in the morning.

I have a rorty gal, also a knowing pal,

And merrily together we jog on.

I doesn’t care a flatch, as long as I’ve a tack,

Some pannum for my chest and a tog on.

I’m a Chickaleary bloke with my one, two, three …,

which leads to repeating the first four lines as a chorus. At the time of the song, Whitechapel was quintessential East End: overcrowded with Irish immigrants fleeing the potato famine and Jewish immigrants fleeing the pogroms, bursting with brothels and other crime, haunted by Jack the Ripper. You needed to be a chickaleary bloke to survive there.

According to Green’s Dictionary of Slang, chickaleary means ‘artful, knowing,’ and a chickaleary cove or bloke (both terms for ‘man’ probably derive from the Roma language or Shelta — see a previous post) is someone hard to take unawares, that is, on the hop or on his tibby drop, and example of rhyming slang compactly in this line of the song. Green uses the song to illustrate rorty meaning ‘fine, splendid, jolly,’ but other quotations with rorty girl or gal are listed under the sense ‘coarse, earthy, […] sexually aggressive,’ which might do, too. A flatch is a ‘halfpenny,’ a tach is a backslanged ‘hat,’ pannum is ‘bread’ or ’food’ more generally, and a tog is a ‘coat,’ a venerable item of cant recorded as early as the almost anonymous B. E. in his A New Dictionary of Terms, Ancient and Modern, of the Canting Crew (1699). Altogether, that’s a respectable cache of slang to extract from a single stanza of a music-hall song, which is one reason Madeline collected Musa Pedestris.

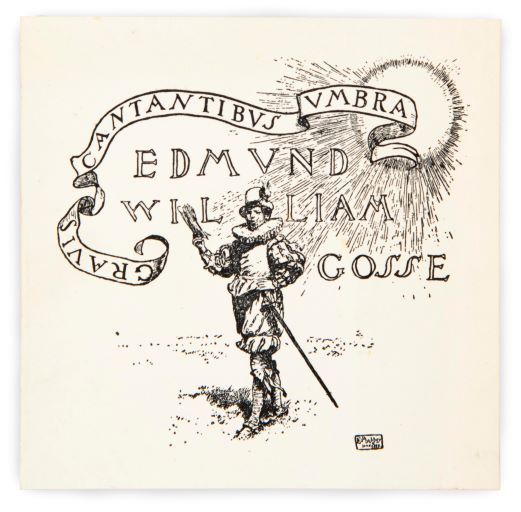

But, as was so often the case, it wasn’t Madeline’s sole curatorial motive. Opening the book, one encounters a bookplate on in the inside cover, that of Sir Edmund William Gosse (1849–1928), librarian, poet and critic, author of the autobiography Father and Son (1907) — in other words, an important person, though less read today than in the twentieth century. The plate is rather ostentatious: besides his full name, Gosse designed a furling banner inscribed with Gravis cantantibvs vmbra (‘the gravely shadowed singers’), a tag borrowed from the last of Virgil’s Eclogues, though Gosse at his best was no Virgil. A seventeenth-century cavalier stands in the center of the bookplate, though Gosse was descended from dissenters rather than cavaliers. As the novelist and critic Anthony Powell once wrote of Gosse, he was “the essence of self-assured self-satisfied literary men,” a stance, like the cavalier’s, illustrated in the bookplate. Gosse owned many books and he believed, as he wrote in the introduction to Gossip in a Library (1891) that “The natural and visible mark of the citizenship of the book-lover is his book-plate,” so it perhaps goes without saying that Gosse’s book plate is far from rare in itself.

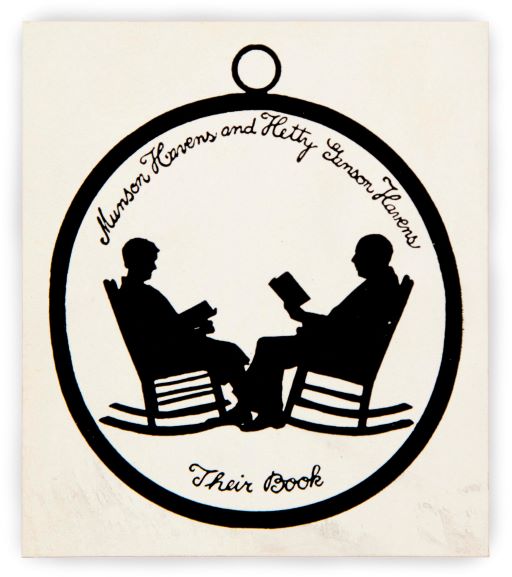

Madeline’s copy of Musa Pedestris has more than one bookplate, probably a record of serial ownership, with the new owners having purchased the copy through Sotheby’s sale of Gosse’s books in 1928–29. Those owners pasted their bookplate onto the verso of the first leaf, announcing themselves as Munson Havens (1873–1942) and Kitty Sansom Havens, and the book as “Their book.” Munson Havens was a reporter on the Cleveland Plain Dealer and later chair of the Cleveland Chamber of Commerce, but he was a literary fellow of sorts, author of the novel Old Valentines: A Love Story (1914), published by Houghton Mifflin, and Horace Walpole and the Strawberry Hill Press 1757–1789 (1901), published in 300 copies on handmade paper by Kirgate Press, in Canton, Pennsylvania — that is, it was published on much the same basis as Farmer’s Musa Pedestris, privately and modestly, with a limited issue.

The Havens’ bookplate is a silhouette portrait of them in facing rocking chairs, toe-to-toe, reading books, intimacy not often the subject of bookplates. It imitates a pendant, with a bail at the top in want of a chain. Rather than a stamp of ownership, it’s a comment on the lives of two old valentines, well-read. In any event, it’s a startling contrast to Gosse’s cavalier and his shaded singers, in all their class and classicism. How odd, one might think that two such different owners perused the same copy of Musa Pedestris, a book that chafes against the ideologies expressed in their respective bookplates.

When I encounter an item like this one in one of the boxes that still house Madeline’s collection, I return to the question of what motivated her collecting, and of course it wouldn’t be just one thing: perhaps evidence of historical slang? perhaps texts associated with dictionaries of slang? perhaps ownership that might figure, footnoted, in cultural history or the history of books and reading? Or perhaps, in this case, a fascination with the varieties of human experience that just a book can capture.

Leave a Reply