Subtitle: “Echoes of Diasporic Community in Reverend Stephen J. Vrabely’s Radio Music Archives”

By Adriane Pontecorvo

(Image credit: Alan Burdette)

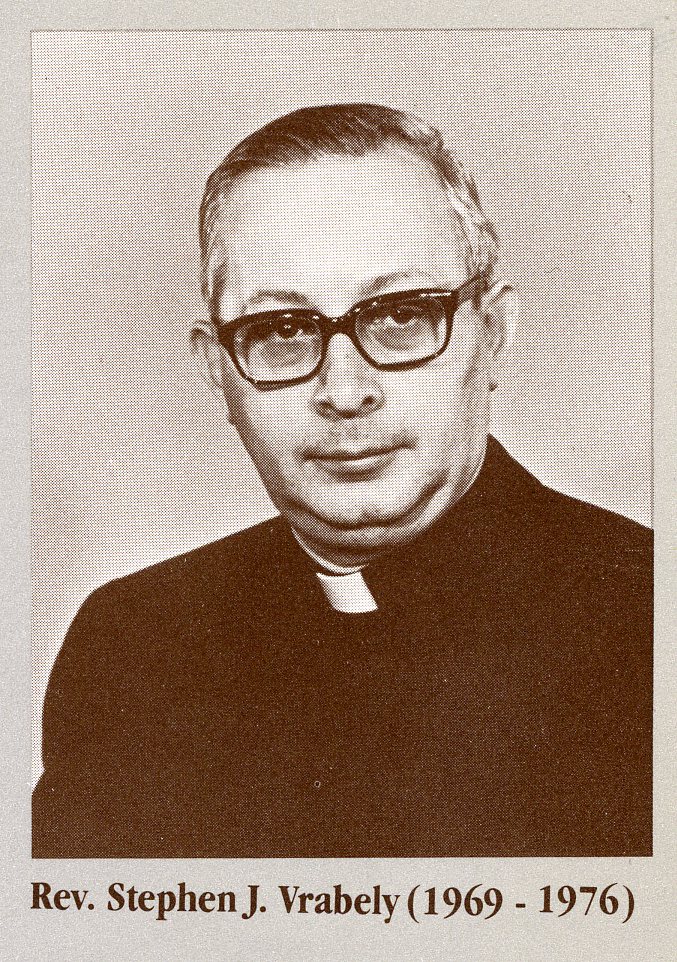

In early 2022, Alan Burdette, former Director of the Archives of Traditional Music (ATM), drove four and a half hours from Bloomington into Kendall County, Illinois, to pick up a donation of around 1400 well-kept shellac, lacquer, and vinyl discs. A gift from the family of Reverend Stephen J. Vrabely (1923 – 1994), the records consist almost entirely of Hungarian music published in the 1940s and 1950s, running the gamut from opera to brass bands to crooning, and featuring some of the most popular theater and radio singers of early 20th century Hungary. For Rev. Vrabely, an Indiana native who spent most of his adult life working in Catholic parishes of the Calumet Region, this collection was important not only on a personal level, but to his work ministering to local Hungarian American communities.

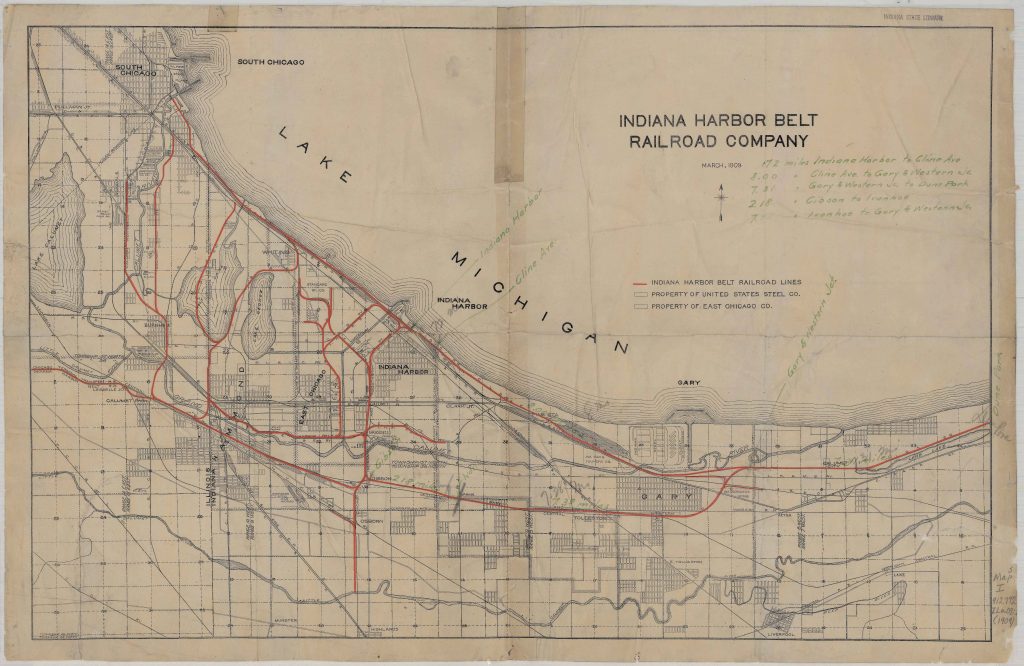

The Calumet Region of northwest Indiana and the industrial cities of Gary, Hammond, and East Chicago has long been a hub for immigrant workers. European laborers, in particular, found jobs in the region’s burgeoning steel and rail industries from the latter half of the 19th century onward. As wars, legislative acts, and other geopolitical shifts led thousands to cross the Atlantic and land in the Midwest, many of the immigrants to “The Region” built ethnic enclaves that grew and changed with each new wave of migrants. In the 1970s, Indiana University (IU) Folklore Institute Chair, Richard Dorson, led two large field research projects that documented Hungarian Americans and other ethnic communities in the Calumet. Now housed between the ATM and the Lilly Library, these press clippings, ethnographic interviews, and field recordings are a testament to the legacy of these migrations and chronicle ongoing narratives of identity throughout the Calumet Region, many of which emphasize ideas of diaspora as key to community and belonging.

Beyond his congregation, Rev. Vrabely deeply engaged such ideas through mass media, specifically the radio. On Hammond radio station WJOB, he co-hosted the Hungarian Hour alongside Cornelius Szakatis; together, they put a vast record collection to work. Dates stamped on the sleeves of the Vrabely Collection discs start as early as the late 1930s–before a 1940 callsign change from WWAE to WJOB–and stretch into the 1960s. The stamped dates raise questions: are thy airplay dates? If so, was the program elsewhere before WJOB? While it will take further research to understand the Hungarian Hour‘s exact origins, we know something of its eventual destination. On WJOB, the Hungarian Hour sat alongside several shows based on ideas of ethnicity, many of them non-English speaking. The station featured Polish, Slovak, Greek, Spanish, and African American programming, offering insight into the diverse audiences in range of the WJOB broadcast.

Media scholar Michele Hilmes explores radio’s role in shaping ideas of identity through the framework of Benedict Anderson’s concept of nations as imagined communities, in which individuals assume they share something fundamental with every fellow citizen, even if they never meet. Hilmes writes that such relationships are based “on assumptions, images, feelings, consciousness” and that it is “the central narratives, representations, and ‘memories’—and strategic forgetfulness—that they circulate that tie the nation together” (2012, 352). In the case of radio, these narratives are virtually always sonic. In any given radio broadcast, voice, music, language, and technology can sound messages that take on meanings inflected by their social contexts and their presence in geographic spaces. Discussing nationalism in the early 20th century United States, Hilmes argues that “the nation found a voice through radio… Yet it would be a mistake to assume that it spoke univocally” (353). WJOB’s multilingual format, chosen with the Hammond-centered listening audiences in mind, is a fairly literal manifestation of voicing a multicultural national identity.

As I take inventory of Rev. Vrabely’s discs down in the ATM vault (at the time of this writing, I have just passed the 1000 record mark), I note recurring names and genres across the labels. Early 20th century singer-actors like Cselényi József, Sebő Miklós, and Mindszenthy István; bandleaders like Magyari Imre and Farkas Béla; and generic references to Romani bands and csárdás folk dances dominate the collection. Even without knowing exactly how Rev. Vrabely framed these recordings on his programs, such common threads shed light on some of the themes he must have found important in maintaining a sense of community among the Hungarian American populations of the Calumet, the imaginaries he felt were crucial for new generations of listeners increasingly removed from the homeland by time and ideology as Cold War-era Hungary moved into a period of communism. By spinning 78s from stars like László Imre and Kalmár Pál, co-hosts Vrabely and Szakatis would have commemorated a selective sense of Hungary to the Calumet Region, one rooted in ideas of both old traditions and contemporary artistry, but decidedly anti-communist.

While there is undoubtedly room for discussion in terms of the “authenticity” of the styles the Hungarian Hour presented—European folk music revivalism and romantic nationalism often go together in complex ways—the Vrabely Collection’s most exciting offering may be its insights into the historical broadcast soundscape of Indiana, and by extension, the United States. The mid-20th century saw an explosion of “local” programming with the potential to counter the homogeneity of national radio networks. By understanding the sounds of such programs, we can better understand the imagined listening communities that shaped and were shaped by radio at the time. Ephemeral aspects of radio, though, often make it difficult to glean any deep insights. The Vrabely Collection is a tangible well of information about how the Calumet Region heard Hungary several thousands of miles across the world. It helps us understand the role of sound and media in transmitting and shaping ideas of place, personhood, and belonging, setting the scene for further explorations of human relations and identity politics in postwar Indiana.

At the ATM, Rev. Vrabely’s music joins other Midwest radio-related materials, from the Donald Lake Collection of country/western dance music recorded for Fort Wayne station WOWO’s Hoosier Hop, recordings of the Greater Harvest Baptist Church broadcasts dubbed by Melville Herskovitz from WAAF Chicago, to the eclectic mix of local bands recorded live for Bloomington community station WFHB and released in the form of various CD compilations (e.g., Acoustic Harvest Firehouse Mix No. 1 and WFHB’s Local Live: Remote Broadcasts. Volume 1 and Volume 2.) Through careful accounting and consideration of such materials, scholars of music, media, community, and diaspora can access critical sonic information that, without careful archival practices, might easily be lost to the ephemeral nature of the radio soundscape.

The Vrabely Collection is a work actively in progress at the ATM. Staff are currently transcribing information from disc labels and putting together an inventory of each item so that they can catalogue, place, and digitize the records as completely as possible. This work will make possible further research into the contents and context of Rev. Vrabely’s personal musical archive.

Works Cited:

Hilmes, Michele. 2012. “Radio and the Imagined Community.” In The Sound Studies Reader,

edited by Jonathan Sterne, 351—362. New York: Routledge.

Adriane Pontecorvo is a PhD Candidate in Ethnomusicology at Indiana University Bloomington. Her research interests include media geographies; community radio; music and place; performance; popular music; and mobilities. She worked as a Library Assistant for the Archives of Traditional Music (ATM) from September 2022 to December 2023 before leaving to spend more time on her research and other scholarly obligations as well as completing her dissertation.

Leave a Reply