Dean Plionis began his career in a number of production-oriented jobs in Boston, Los Angeles and Philadelphia, having studied film and television at Boston University. Currently, he serves as the Director of Operations at Colorlab, a position that requires him to ensure the company’s efficient operation in preserving films and processing negatives. He notes that his transition from technical work to preservation work was a challenge, in that he had not previously been exposed to the world of film preservation. This transition is something he feels is “representative of most peoples’ experience in modern productions…there are schools and programs that do teach a lot of film handling and curating skills, but in general there’s a good deal of on-the-job training and education. We work with such a huge variety of film formats, splicers, printers, and video and digital equipment that it’s not realistic to expect any one candidate to have all of that experience.”

Colorlab staff members, including Plionis himself, have hyphenated responsibilities; such multitasking in laboratory work is considered the norm in an increasingly digital-oriented preservation landscape. “There’s this hybridization of new digital and original mechanical technology, techniques, and workflows that’s been evolving over the last five to ten years and will continue to do so in the future,” Plionis notes, adding that more traditional workflows require an evolving, DIY skillset, particularly given declining manufacturer support and frequent modification and maintenance of preservation equipment. “Most productions originate on digital platforms now and each year, fewer of those productions are backed up or archived to some sort of physical medium…it’s not really an archival-friendly environment because the footage doesn’t exist in a physical form.”

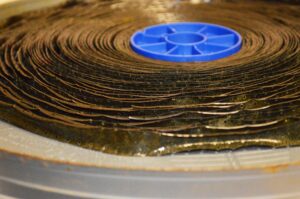

Plionis says the biggest misconception people have about film is that it is inaccessible; he argues that digital and video formats are often less accessible than film, due to the lack of regularly-maintained technological support systems and the difficulty of reverse-engineering in accessing data. He cites recent industry discussions regarding 2” Quad tapes, the video format that was introduced in the 1950s – this format is no longer used in production and many in the preservation field are concerned about what continued efforts will be made once the last video heads for the format are produced. “Once the data encoding standards change – as they do regularly in the digital realm – all bets are off if that data is not continually migrated. The context of time over a period of decades needs to be considered when it comes to evaluating the ‘accessibility’ of any given media format, and film has certainly withstood that test,” he says, adding that “there have been studies showing that the long-term costs of preserving data to film are actually lower than preserving data digitally, once you factor in the costs associated with continually migrating digital data and upgrading computer systems in order to keep up with technological changes. A newly-made film stored in a climate-controlled environment can last a hundred years or longer with minimal maintenance.”

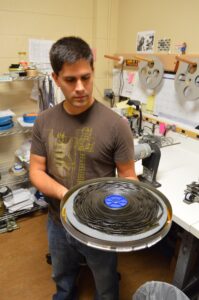

Thus, while other formats have come and gone, film has remained a consistent presence in the preservation field, due in part to what Plionis refers to as the “human-readable” advantage of the medium – the images housed on a reel of film can be viewed by the human eye in a way digital images cannot. “From a technological standpoint, all that’s needed for a motion picture film is a light source and some sort of shutter, which people will always have the ability to recreate…original films really are the ultimate masters that preserve your ability to go back and re-visit the material as technology and standards change.”

Yet film preservation carries unique challenges. Plionis says, “the most difficult challenge the field of preservation faces is that it requires the allocation of time and resources today for the payoff of people having access to it a generation or two later. Will they care, be thankful, and in turn, take it upon themselves to pass on this data to future generations? There’s an element of trust involved that your preservation methods will hold up and that there will be someone waiting for it on the other end of time.” Format-specific preservation challenges are often represented by conflicting goals: Colorlab staff are charged with preserving the film, manipulating the image and sound as little as possible, while simultaneously correcting or repairing damage that has occurred since the time of creation. Of Colorlab’s processes, Plionis notes, “we prefer to use photochemical processes to fix issues where we can, such as using liquid-gate when printing intermediates to naturally hide base scratches or rewash treatments to soften and anneal scratches in the emulsion. Digital methods are still used but there is definitely an aspect of fixing an image too much, just like you can ‘photoshop’ an image to the point where it looks fake and inauthentic. In general, we have a more minimalist intervention perspective and we certainly won’t add color to a B/W image that never had color or do anything like Spielberg or Lucas did with reissues of their older films where they digitally removed the guns from the hands of agents or added CGI over their original effects.”

At the end of the day, Colorlab staff defer to clients, as the stewards of the films, to make decisions regarding preservation. “We feel it’s more our job to stand back and explain the options available,” Plionis says, citing a recent project in which a client requested the addition of an explanatory title card in an incomplete silent film: “The question then becomes, do we try to make that title card match the exact style of the other inter-titles or not? Maybe that’s too ‘interpretive’ while the other may disrupt the viewing experience if it seems too out of place.” Questions of authenticity become a discussion between client and staff, with Plionis adding that “choices like that are really the client’s to make.”

In addition to working with clients on preservation projects, Colorlab staff regularly provides outreach by attending archival conferences and conventions such as AMIA, The Orphan Film Symposium, and The Flaherty Film Seminar, often participating in technical discussion panels. The company occasionally takes on interns, but the high learning curve that goes into training and education is often a deterrent.

Currently, Colorlab staff are working on several high-profile projects, including preservation of original production and interview outtakes from the civil rights documentary Eyes on the Prize, a documentary about Carnegie Hall’s 1986 renovation, The 28-Week Miracle, and a film called Nenotri I Dyte (The Second November), for the Albanian Cinema Project, an effort to introduce historically-isolated Albanian cinema to global audiences for the first time. Additionally, Colorlab recently provided archival transfers to Ken Burns for his upcoming 7-episode documentary, The Roosevelts.

Though Plionis believes that film’s days as a mainstream production format are numbered, he doesn’t see the format going completely away: “there will always be a group of people devoted to it, just like there’s always a group of people devoted to using any other obsolete format and technology.” Film’s greatest advantage, he argues, is in its use as a preservation format, “given its time-tested resiliency, its human-readability, and the fact that a projector or other scanning equipment can always be reverse-engineered…the key to seeing film survive in this format is basically tied in with the larger argument for preservation.”

~Kaitlin Conner

Leave a Reply