By Rachel Makarowski

This post is part of a series written by students in ILS-Z681, The Book: 1450 to the Present. This course is taught by Lilly Library Head of Public Services Rebecca Baumann through Indiana University’s Department of Information and Library Science.

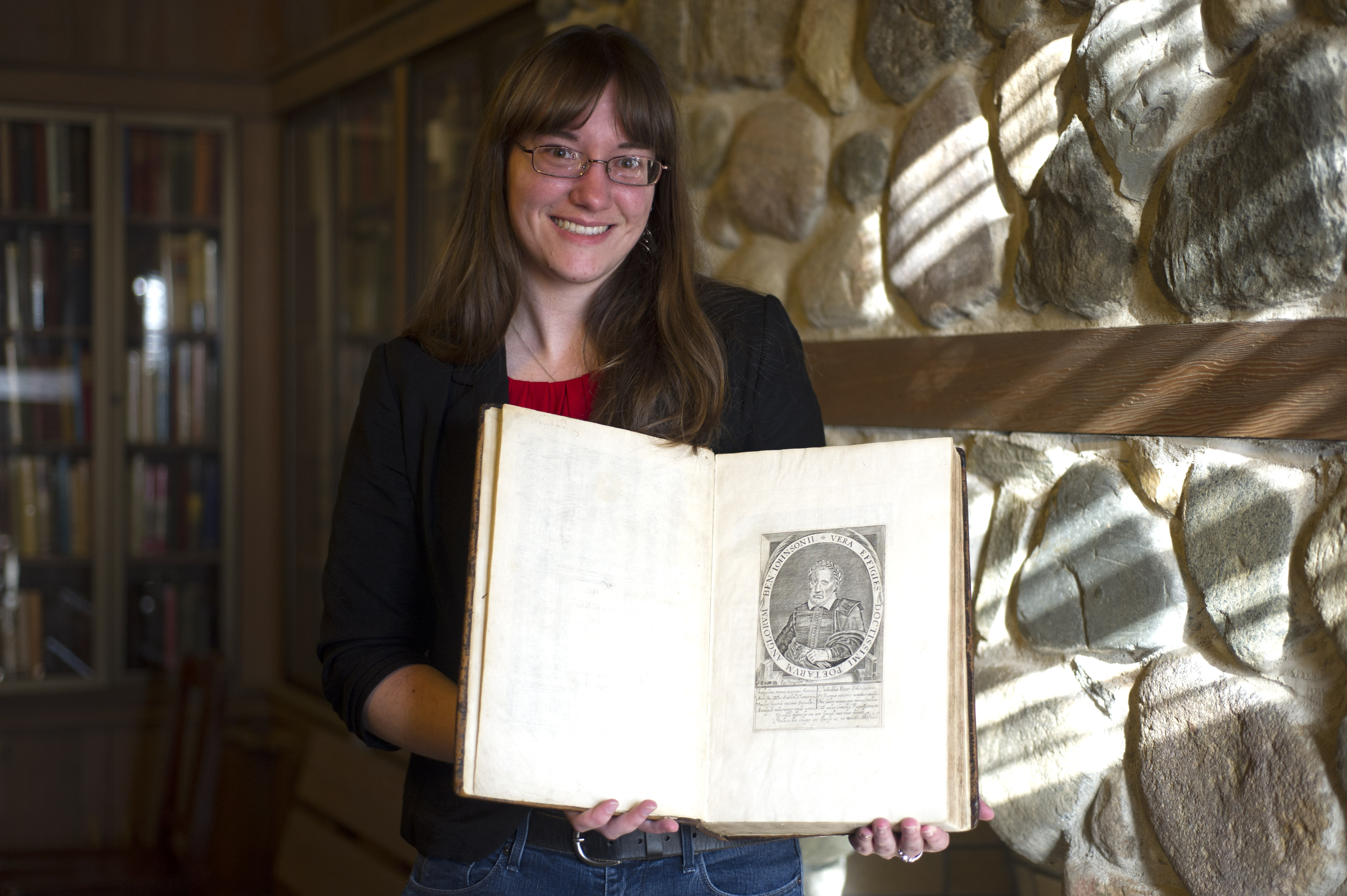

The 1616 folio edition of Ben Jonson’s plays does not get as many requests at the Lilly Library as its more famous successor, the 1623 first folio edition of Shakespeare. It is not particularly remarkable in appearance to the average eye, with a leather binding roughed and worn with age. From the outside, it looks relatively humble. Although this folio lacks fame and ostentatiousness, the riches within reveal quite a bit about the author and the world of English Renaissance drama in print.

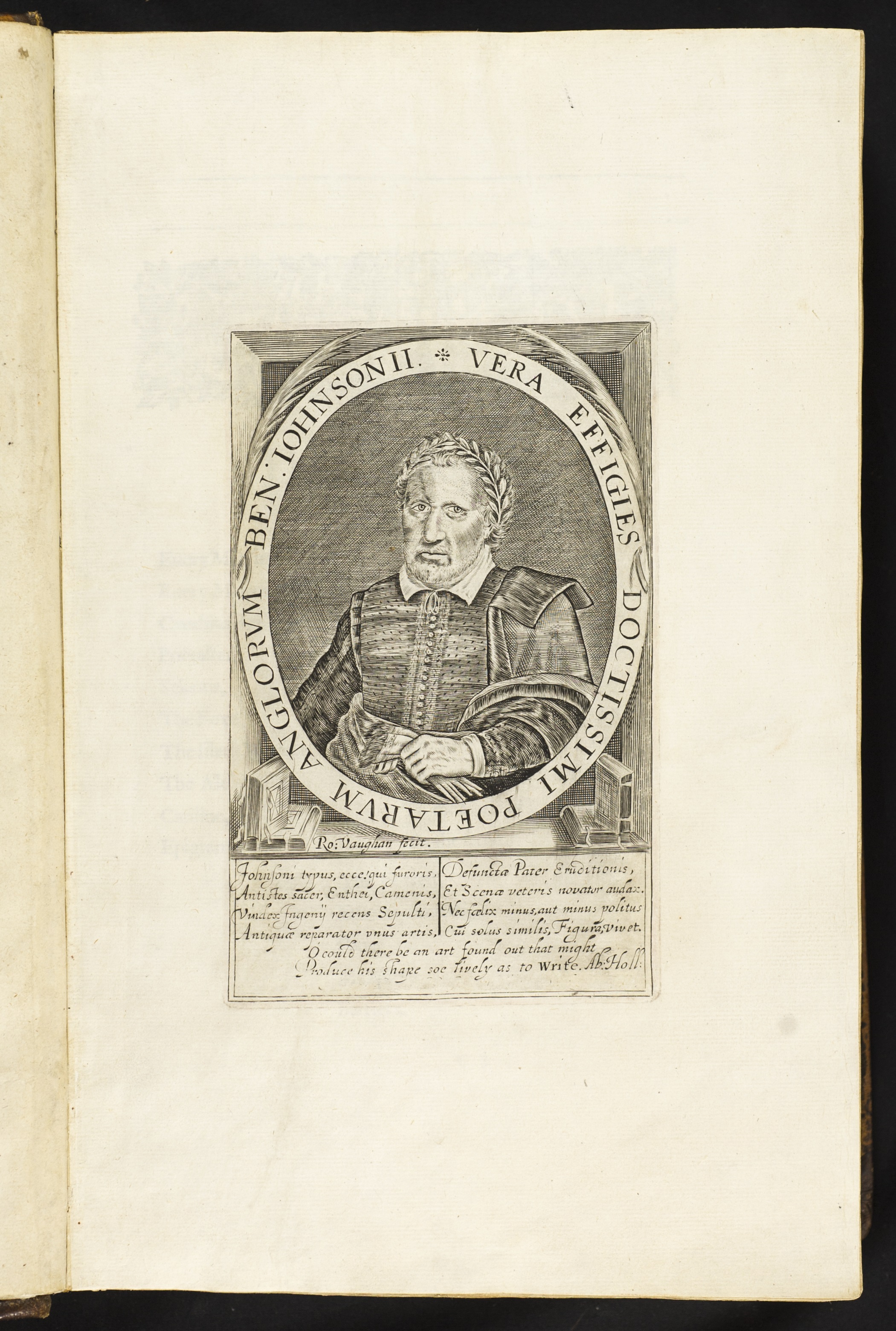

At the beginning of the book, the reader can find an author portrait. This picture was not a part of the original 1616 printing of the folio, but was “tipped in”—that is, attached to the page during the binding process. Jonson’s fine clothes and large stature portrayed in the depiction allude to a man who enjoyed the finer things in life. A laurel crown rests upon his head, as if crowning his prestige and victory. Cnircling this picture are the words: VERA EFFIGIES DOCTISSIMI POETARUM ANGLORUM BEN: JOHNSONII (“A true effigy of the most learned of English poets, Ben Johnson”). This wording is far from humble; he is not just a learned poet, but the most learned. Being considered as such was important to him. But why is this so?

Ben Jonson did not come from a prestigious family or a wealthy class. His stepfather was a bricklayer, and Jonson served as his apprentice for a number of years. Like many bricklayers, he did not have a formal education at the university level. Despite this disadvantage, he ensured that he knew Latin, the educated language of the time. He left his stepfather’s profession to join the military. It was at this point in his life that he gained an interest in the theater and became an actor and continued on in this capacity after his return home (Drabble 540).

During his acting career, his self-taught skills in Latin saved his life. He murdered another man during an argument and went to jail. The punishment for such a crime was death, unless the offender could prove he was a cleric and thus gain religious exemption. Jonson claimed to have such status, arguing that he should be released from his punishment. To prove his claim, authorities asked him to read from a Latin religious text. Jonson successfully did this and was then released. After this, he left acting to become a full playwright (Hartnoll 524).

Even after this incident, he still was determined to proclaim his familiarity and love of Latin and the classics. He included the language in several places throughout the 1616 folio, quoting untranslated lines from classical authors, including Ovid and Vergil. His love of classics can even be seen in the title page, which contains multiple figures, such as Comoedia (a personification of Comedy).

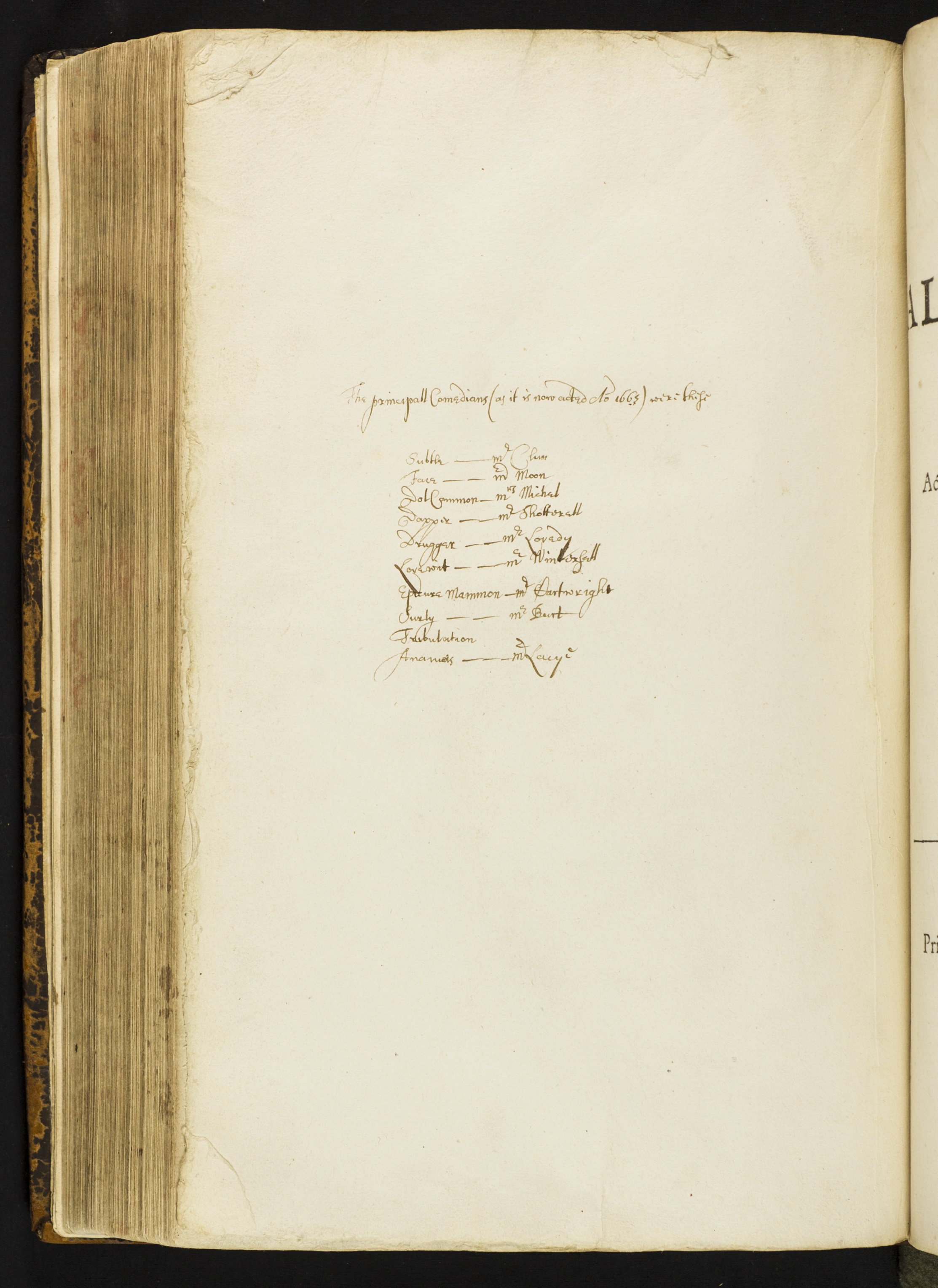

The 1616 folio conveys evidence of who Ben Jonson might have interacted with in the form of the cast lists that follow each play. Although these lists do not provide information on who played what character, these lists are still useful in that we have printed proof that these people were involved with Ben Jonson, at least nominally, if not personally. Some of the people on the cast lists are unfamiliar, even to scholars; others, however, are surprisingly well known. William Shakespeare, for instance, is included on the cast list for two of Ben Jonson’s plays.

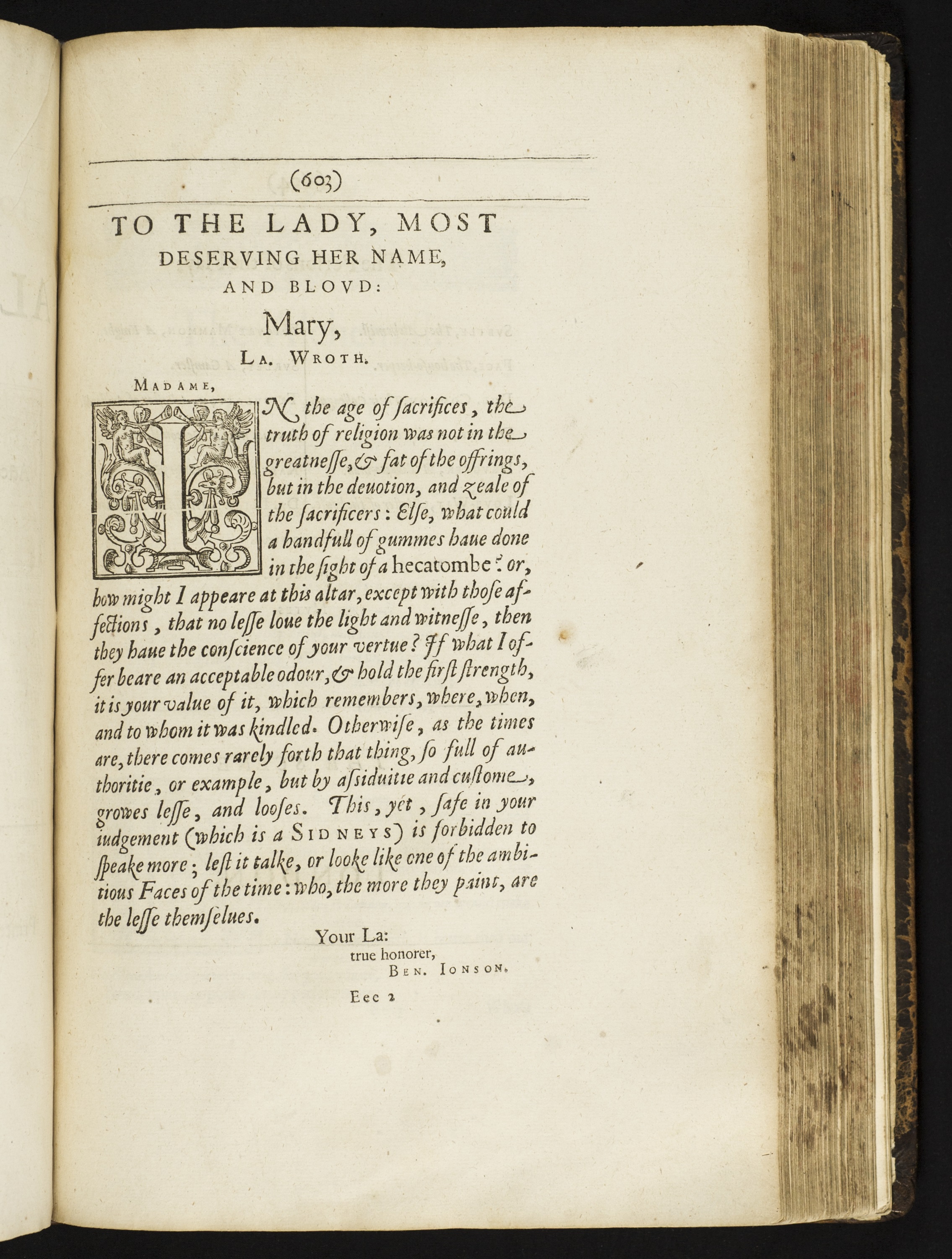

It was common for authors and playwrights to have a patron who would pay a sum of money that would help to supplement the writer’s income. In return, the author would dedicate works to his patron or write something that relates to the patron’s life. The 1616 Folio exemplifies this practice. Jonson included letters to specific people before each play. Some of these would be to friends and fellow poets, whereas others would be dedicated to those who could or already did support him by becoming a patron of him.

He also included a series of advertisements written by contemporaries and friends at the beginning of the folio at the beginning. These express the wit and intelligence of Ben Jonson and his works. They were included to encourage readers who might appreciate these features to purchase his book, and to attract more elite patrons who could not only afford the book, but also afford to support him in his career. How he gathered these advertisements is unknown, though he was a charismatic and friendly enough person that he could have convinced his friends and contemporaries to do this on his behalf.

These are all elements that we can be sure were placed in the folio with Jonson’s approval, and maybe even his insistence, to gain a higher class of readership. Jonson was heavily involved in the creation of this folio. He took older quartos of his theatrical works and edited them to varying degrees before passing them off to be printed (Pforzheimer 573). Acrostic poems preceded each play in the 1616 Folio, which would not be a part of the play when acted but were intended for his higher class readers who would be familiar with the classical works that use this as an introduction for select plays. Jonson intended these higher class readers to enjoy reading his works. They would have the education and background to appreciate all that he had included in the folio, much more so than those of a lower background.

The 1616 folio was both immense and important at the time of its creation, if only because of the hand the author had in its creation. It gives valuable insight to both scholars and casual observers about Ben Jonson and the larger scene of the theater in the English Renaissance. However, if what can be gleaned from this book is combined with the other plethora of English Renaissance material, anyone interested in this time period would be sure to find a treasure house replete with information.

Works Cited

Drabble, Margaret, The Oxford Companion to English Literature. 6th ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Hartnoll, Phyllis. The Oxford Companion to the Theatre. 3rd ed. London: Oxford University Press, 1967.

Pforzheimer, Carl H., Emma Va Unger, William A Jackson, Frederic Warde, Bruce Rogers, and Josiah Kirby Lilly. The Carl H. Pforzheimer Library: English Literature, 1475-1700: Volume 2. New York: Privately printed, 1940.

Rachel Makarowski is currently completing her Masters in Library Science with a specialization in Special Collections in Indiana University’s Department of Information and Library Science. She has an interest in medieval manuscripts, early modern print culture, and the book in East Asia. She hopes to find a full time position in public services at a special collections institution.

2 Comments

This is a very informative post. Thanks.

In 1994 (I believe), the handwritten cast list of The Alchemist shown in this article was examined by Kelli Wondra, a PhD student in Theatre and Drama. She checked the actors’ names against known, published cast lists of early performances of the play (just to see which theatre company’s performance the original owner of the book had seen and recorded). She discovered that the original owner had seen a previously unknown early performance of The Alchemist; Ms. Wondra shared her find in an article published in Theatre Notebook, Vol. 49, No. 2 (http://www.str.org.uk/notebook/archive/49-2.shtml).

There’s a lot to be discovered in the Lilly Library.