Madeline Kripke’s phenomenal collection abounds with big dictionaries, old dictionaries, and big old dictionaries, but it also includes some very small items.

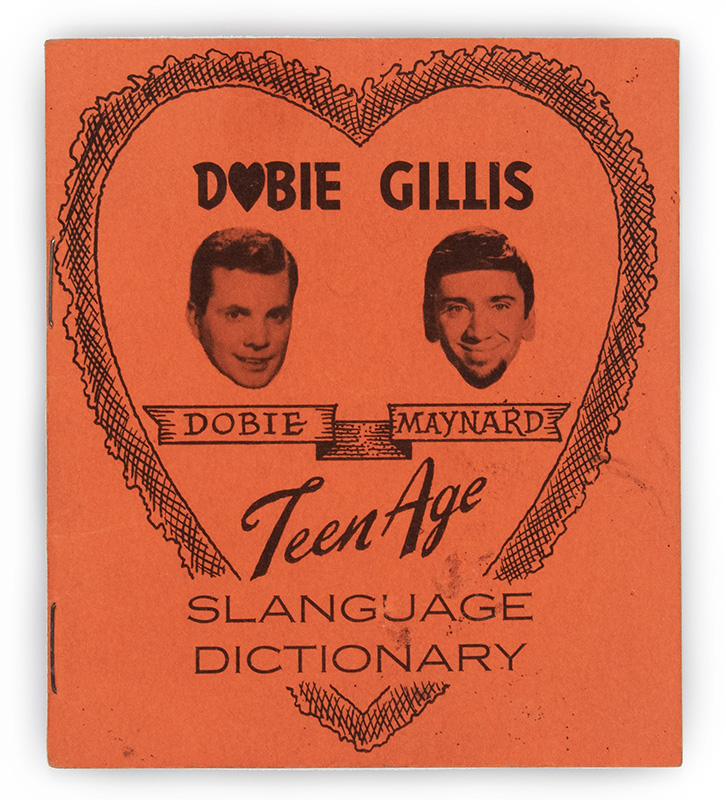

The Dobie Gillis: Teenage Slanguage Dictionary (1962), just sixteen pages measuring 4 x 3.75 inches, was published by 20th Century Fox Television and Selby-Lake Inc., the latter an advertising agency. It’s a marketing device to consolidate a brand. It trades on the supposed currency of the lingo included as a record of, in its own words, “Teen-age antics and terms.” The 1950s and early 1960s marked the rise of teenage culture and teen-targeted marketing. There’s no lack of evidence for the phenomenon, but the Dobie Gillis dictionary is part of that evidence.

The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis, adapted by Max Schulman from some of his short stories, aired on CBS for four seasons (1959–1963). Dobie has an irascible father and a doting mother and an unrequited lover, Zelda. It all stinks of 1950s innocence. For television, Schulman added a character, Maynard G. Krebs (played by Bob Denver), who loved jazz and represented the Beat Generation. It was the first American television show to explore the counterculture, even if it was a rather light treatment.

Thirty years later, Denver wrote, in Gilligan, Maynard, and Me (1993), that “This was the late fifties and beatniks were the funkiest things around.” To prepare for his role, he went “to coffeehouses in L.A. where beatniks hung out” and “listened to their beat poetry and jargon.” This was early television, and Denver thought that “not too many of the writers knew what a beatnik was like,” so he was allowed to invent his character. That explains the slang in the series, but the slanguage dictionary went further than the sitcom, filling in a slang backstory and drawing the telefictional world closer to the language and culture of real teens.

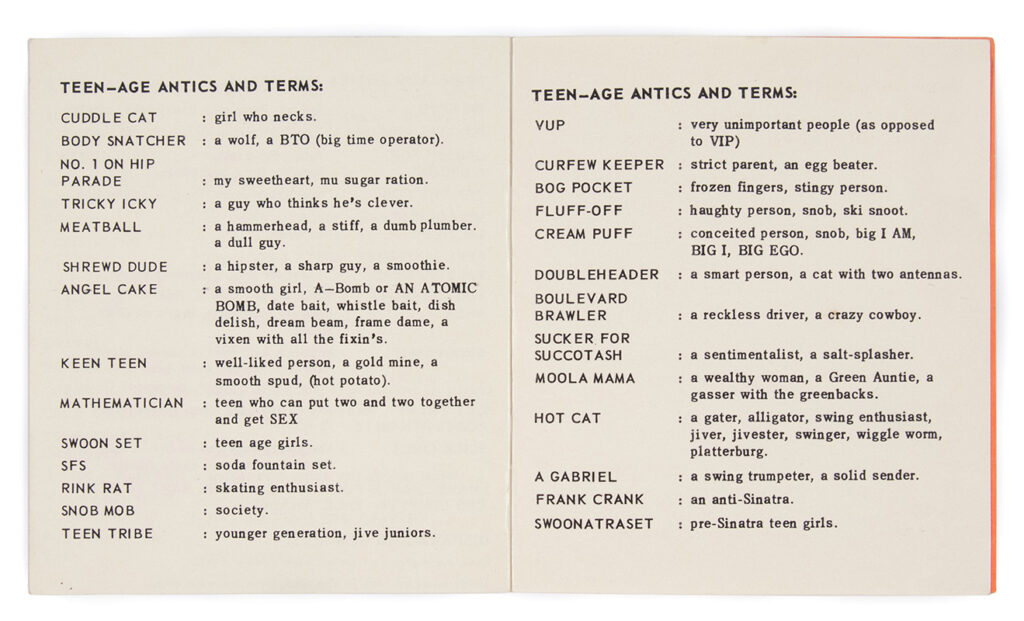

The pamphlet’s slanguage is vivid and clever, but is it authentic? Consider these two sample items:

ANGEL CAKE: a smooth girl, A-Bomb, or an atomic bomb, date bait, whistle bait, dish delish, dream beam, frame dame, a vixen with all the fixin’s [sic].

MATHEMATICIAN: teen who can put two and two together and get SEX.

Green’s Dictionary of Slang (3 volumes, 2010) doesn’t enter mathematician in this (or any other) sense, and angel cake is missing, too, but smooth in the sense captured in smooth girl and dish in dish delish both appear in long entries, and one finds date bait and whistle bait in GDoS, too, all senses concurrent with Dobie Gillis and his many loves.

Perhaps the other items are also authentic but rarely attested in print. The Dobie Gillis glossary is not listed in Green’s comprehensive bibliography, and perhaps Jonathon Green never saw it, as unlikely as that seems, given his almost supernatural command of slang at its sources. Thus, it may also preserve evidence of overlooked slang.

Is the Dobie Gillis: Teenage Slanguage Dictionary a dictionary or a thesaurus? After all, it defines entry words with synonyms and, unlike professionally made dictionaries, it doesn’t define all the words in its definitions. I suspect the makers of the booklet didn’t care about the difference. Although dictionary conventions are employed, they are actually misleading: capital letters or small capital letters usually indicate a cross reference, but across the whole work, they don’t. This tiny dictionary imitates dictionary conventions without following through on them — it has the look of a dictionary, which is what Selby-Lake was going for.

The marketing geniuses at Selby-Lake appropriated the authority of dictionaries to raise the status of slang but doing so tongue-in-cheek also challenges the status of dictionaries, by lowering the level of dictionary discourse and taking lightly what credentialed lexicographers usually take seriously. The Dobie Gillis slang dictionary is a sort of slanging of the dictionary format, a way of turning it against the authority it represents in the mainstream.

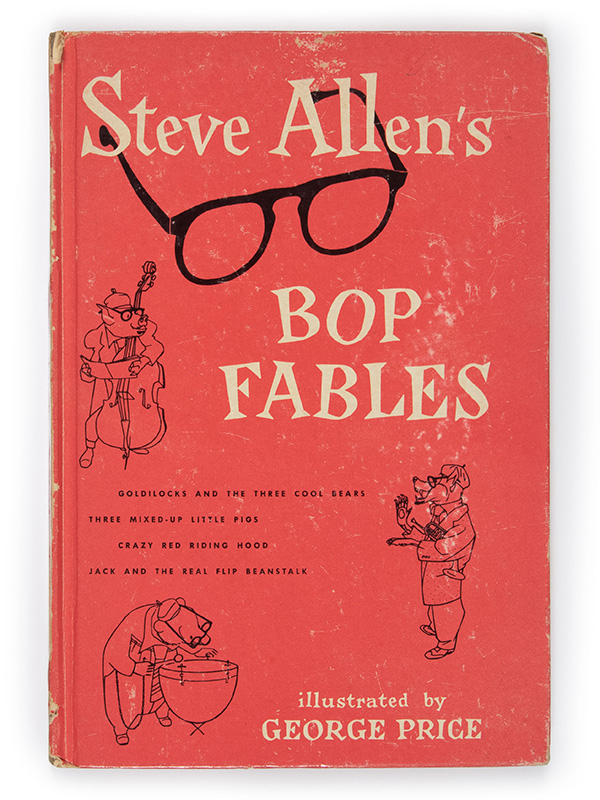

The Dobie Gillis dictionary wasn’t the first attempt to fuse slang with television marketing, nor was it the only slangy work with a television connection that Madeline collected. Steve Allen, the comedian and talk show host who debuted The Tonight Show in 1953 and then The Steve Allen Show in 1956, took some time between those projects to write Steve Allen’s Bop Fables (1955), illustrated by The New Yorker artist George Price, and at 86 pages a book a little less little than the Dobie Gillis dictionary. For a dollar, readers could experience bop retellings like “Goldilocks and the Three Cool Bears,” “Three Mixed Up Little Pigs,” “Crazy Red Riding Hood,” and “Jack and the Real Flip Beanstalk.”

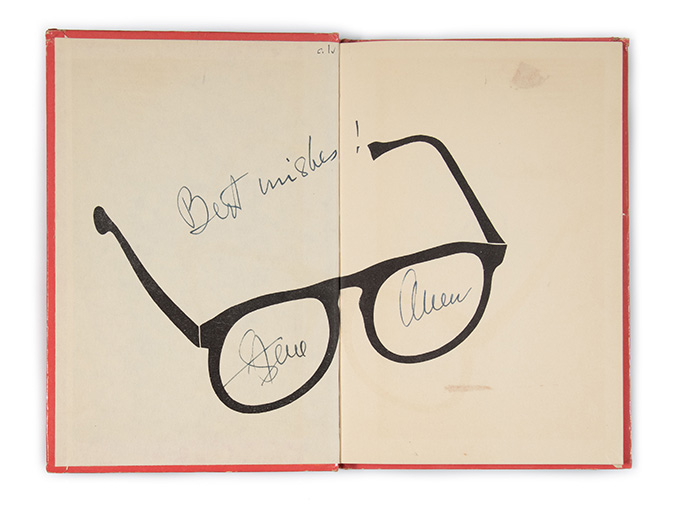

The book has fun with the slang of that time, but it also advertises the author. An author blurb describes Allen as “a bespectacled young writer,” and his signature glasses appear in the author photo, on the cover, and inside, where Allen autographed Madeline’s copy, one name for each lens. Allen sent that copy to the residents of the “Sarasota Welfare Home, c/o Mrs. William M. Lyda, Celebrity Chairwoman, 1501 North Orange Avenue, Sarasota, Florida,” from his home at “1539 North Vine Street, Hollywood 28, Calif.” — we know this from a mailing label saved and inserted into the copy. Note that back then addresses didn’t have zip codes; note that welfare homes had Celebrity Chairs who contacted the likes of Steve Allen on behalf of the residents. None of this has to do with dictionaries or slang, but it’s valuable cultural information enshrined in one of Madeline’s books, all the same.

Here’s a sample of one of the bop fables:

Shortly thereafter the downstairs door banged open and in walked three bears. “I smell Arpege,” said the mama bear to her mate. “Gus, you’ve had a broad here.” “You’re out of your skull,” said the papa bear, “although it does look as if somebody had eyes for soup over there.” “I’m hip,” said the mama bear. “And dig! The upstairs bedroom door is open.”

Tame stuff today, but apparently a wild ride for squares in 1955!

Leave a Reply