Content note: This blog post contains a book title which uses a historical term for the Roma people now increasingly regarded as offensive because of negative stereotypes associated with that term.

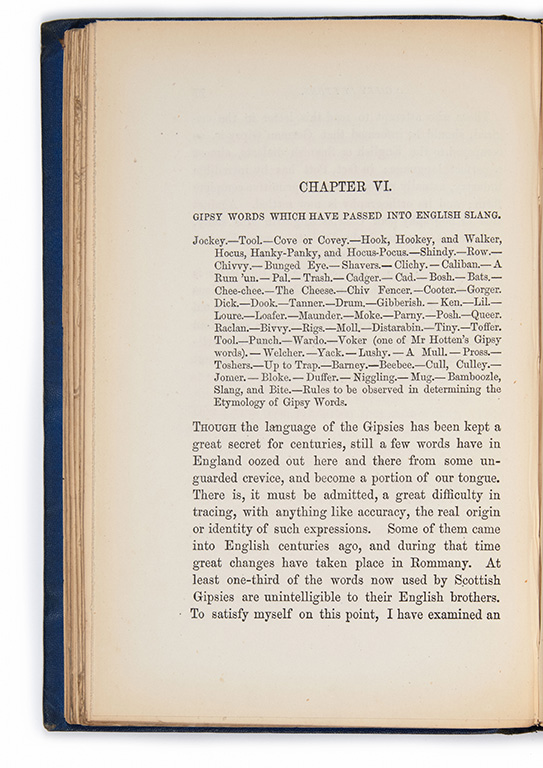

Slang dictionaries have long claimed Roma etymologies for various words. Some people believe that slang churns up from the criminal element, the stigmatized Roma people assigned by the overworld to the underworld, find responsibility for the supposedly low element English and other slangs unfairly thrust upon them. Green’s Dictionary of Slang (2010) inserts Roma into the etymologies of just 258 senses in 113 entries (from a total of roughly 100,000 entries) and the OED proposes just nine etymologies from Shelta, a British extension of Roma language. As someone interested in slang and slang lexicography, Madeline Kripke sought out books about Roma people, their language and culture, and the supposed effect of Roma on the developing vocabulary of English and other European languages. Roma influence on English slang is a bit of a language myth, but no account of the slang phenomenon would be complete without considering and refuting it.

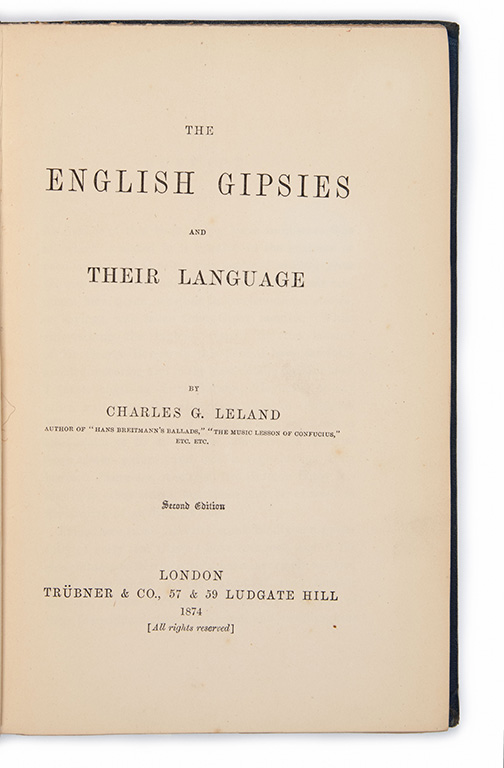

Charles G. Leland (1824–1903), an American folklorist and ethnographer, cast a sympathetic eye on the Roma people when few did. His The English Gipsies and Their Language (1874) approached its subject with historical and linguistic precision:

The Romany English vocabulary which I propose shall follow this work is many times over more extensive than any before ever published, and it will also be found interesting to all philologists by its establishing the very curious fact that this last wave of the primitive Aryan–Indian ocean which spread over Europe, though it has lost the original form of its subsidence and degradation, consists of the same substance — or, in other words, that although the grammar has wellnigh disappeared, the words are almost without exception the same as those used in India, Germany, Hungary, or Turkey. It is generally believed that English Gipsy is a mere jargon of the cant and slang of all nations, that of English predominating; but a very slight examination of the Vocabulary will show that during more than three hundred years in England the Romany have not admitted a single English word to what they correctly call their language.

As John Considine argues in his Small Dictionaries and Curiosity: Lexicography and Fieldwork in Post-Medieval Europe (2017, Chapter 7), Roma language had been an object of fieldwork and the lexicographical record long before Leland, in fact, in the sixteenth century. Not a dictionary per se, Leland’s work includes a glossary of Roma language, which made collecting it essential for Madeline, as part of that lexicographical record.

Leland’s is not the only work on Roma culture and language in Madeline’s collection. Heinrich Moritz Gottlieb Grellman (1756–1804) wrote the earliest serious ethnography of the Roma people in Die Ziguener: Ein historischer Versuch über Lebensart und Verfassung, Sitten und Shicksale dieses Volks in Europa nebst ihren Ursrunge (1783), translated into English by Matthew Raper (1742–1826) as a Dissertation on the Gipsies, being a historical inquiry (1787). Raper was a Fellow of both the Royal Society and the Society of Antiquaries. He dedicated his translation to Sir Joseph Banks, who was President of the Royal Society (1778–1820) when the book was published. Leland refers to Grellman in The English Gipsies and Their Language, but whether to the German original or the English translation is unclear.

Little English slang derives from Roma words, yet slang lexicographers have long claimed a stronger connection. John Camden Hotten’s brief history of cant at the front of his Dictionary of Modern Slang, Cant, and Vulgar Words (1859), of which Madeline collected several copies of several editions, claims that criminal language entered England with the Roma during Henry VIII’s reign, which is almost assuredly not true — medieval England was rife with Anglo-Celtic, Anglo-Saxon, and Anglo-Norman criminality. Hotten’s dictionary was popular into the twentieth century — the last version of which I’m aware appeared in 1922. So, the relationship between the two, Roma and slang, has been in people’s minds for a long time, all of it predicated on prejudice against the Roma people. It’s an ironical shame that Leland’s book appeared the year after Hotten died and in the same year as the fifth edition of Hotten’s dictionary. As Considine observes, motives for Roma peoples’ use of a cryptolect, or secret language, are much more complex than criminality — out of respect for Roma people, cryptolect is a better word for what they spoke and speak than cant.

Both Leland’s and Grellman’s books, however, are serious ethnography, remarkable given the century-span in which they were published. Even with the faults of ethnographic thinking at the time, it’s good to have resources that explain the Roma people and their historical experiences as thoughtfully and accurately as possible, and these books both point in the right direction. The ethnography and lexicography augment each other. Madeline saw that: though not a dictionary, she bought Raper’s translation of Grellman for $975.

When I encounter non-dictionary books like these in Madeline’s collection, I wonder whether she has some corresponding dictionaries. Perhaps, in some other boxes, I’ll find those early dictionaries that record Roma language mentioned in Considine’s chapter, but also works like the Multilingual Romani Dictionary (1978) — which translates across Roma, English, Hindi, Russian, and French — and the Romani–Punjabi–English Dictionary (1981), both by the Indian linguist and diplomat W. R. Rishi. Or, more recent and discriminating dictionaries, like Ronald Lee’s Romani Dictionary: Kalderash–English (2010) — Kalderash is the Roma language spoken in Romania — and Romani Dictionary: Gurbeti–English/English–Gurbeti (2011) — Gurbeti is the Roma language spoken by those located in states that replaced the former Yugoslavia — by the Bosnian journalist and Roma scholar Hedina Tahirović Sigerčić. Or even Terence Patrick Dolan’s Dictionary of Hiberno–English (2004), which records Shelta’s effects on the English of Ireland. Shelta is often referred to as “the Cant,” which brings us back around to Hotten’s understanding of Roma language as language of the historical underworld.

Well, so much for musing about what I might find. Better to spend more time among the boxes of the unpacked Kripke collection actually finding it.

Leave a Reply