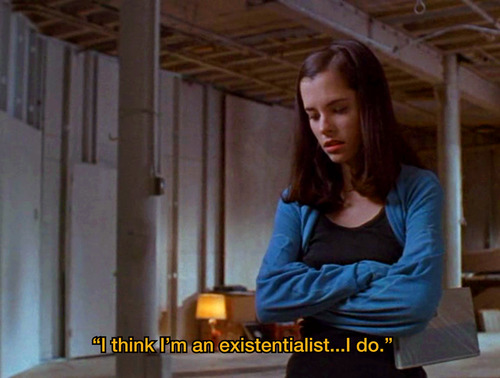

“Party Girl” (1995), Parker Posey’s feature debut, has the dubious honor of being the first commercial comedy-drama film to be broadcast in its entirety over the internet. Over twenty years later, deep in the internet age, it still provides plenty of #inspo fodder for blogging aesthetes and fashion magazines due to the remarkable work of its costume designer Michael Clancy. Indeed, Clancy’s genius (in conjunction with Posey’s performance, the ‘90s house soundtrack, and the high school existentialism)

is what draws me back to this movie every few months: his intentional design work creates readable surfaces throughout the film–the clothes become a text, in a (tactile?) sense.

Posey’s character Mary is epitomized in reviews as a wayward girl whose only preoccupations are amassing a couture wardrobe and attending “it” functions. That is, until she’s arrested for hosting an illegal rent party and must pick up a clerk job at the library to cover bail. She’s a reluctant worker, but finds over time–through acknowledging the potential Sisyphean value of the drudgery–that she may have an innate skill for library work. She also strikes up a romance with the falafel vendor on the corner, all the while turning look after look, in the stacks or at the club.

Though denigrated as a focus of her superficiality in synopses, Mary’s wardrobe is a sartorial text itself–through “reading” the ways in which Mary utilizes, interacts with and conceptualizes the material objects of her adornment process, we can see the root of her particular intelligence.

Early in the film, after her first few days of work at the library, Mary is at her loft with her friend Derrick trying to figure out what to wear for the night. We see her closet and the fastidious way in which it is organized conceptually and physically: she maintains a “diva velvet glam” section (among other “looks”, presumably) and even keeps her denim neatly folded on hangers (“Yes, Derrick, they’re jeans, and they’re in order, don’t mix them up!”). She approaches her wardrobe with reverence, and clearly delights in maintaining and deploying it.

Through montage, we watch Mary as she walks to work, takes her lunch breaks, shelves books: the quotidian is made consequential through the pomp of her dressing. We see that individual pieces are reused and reapplied, and we can track their movement from outfit to outfit (white sneaker-clogs, leopard stole, green brocade jacket); rather than imply that Mary’s wardrobe is overflowing, Clancy makes clear to us that she has limited stock but savvily knows how to use it–she doesn’t have a collection of discrete outfits, but a veritable infinity of potential permutations.

Even individual items are variant–take, for example, these amazing Comme des Garcons shirts that are present during some of the film’s most meme-able moments. From scene to scene, we see them subtly change in length, cut and proportion. They also serve as Mary’s outfit for her stoned dance party-cum-shelving marathon : the real moment she discovers she might be good at this whole library thing. These subtly-shifting shirts follow Mary from the nadir of failed coding to the zenith of decoding Dewey.

We see then that Mary has a clear knack for organization and (re)configuration–skills that were at first made manifest through dress. This intelligence, however, is not recognized when present in such a feminized medium–only when Mary applies her aptitude to an established system (the Dewey Decimal Classification, notorious for its inhospitability to anything outside white patriarchal hegemony), does it then become legitimate. This is shown literally when Mary must sell the material bearers of her sagacity in order to pay rent and attend graduate school. So, here, the bildungsroman is not about the accumulation of emotional or social intelligence, but instead the sublimation of a feminine intelligence to a patriarchal order.

“Party Girl” is available in our Browsing Collection here at Media Services in the Wells Library.

Stay tuned for “Clueless” (1995), the movie that launched a thousand .gifs.

-william

1 Comment

Great analysis, I’ve loved this movie since it came out and watched it many many times and somehow it never occurred to me that mary catalogues her fashion like a librarian!