In April, we had a lovely visit from the Guild of Book Workers / Midwest Chapter, while they were in Bloomington for their annual meeting.

In General Collections Conservation, aka the Book Repair Lab, we discussed the many changes in academic libraries that have led to an evolution in book repair practices, and showed the group some of the newer treatment techniques we are using today. Here I reprise some of that discussion, and then describe one of the board reattachment methods we demonstrated for them, called “thread staples.”

Changing Practices to Meet Evolving Needs

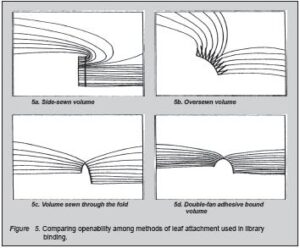

Preservation practices must be able to respond to new patterns of use, and to collecting strategies that are constantly evolving. In the earliest days of library preservation programs, for example, a new type of use — the photocopy machine — helped lead to improved methods in commercial library binding. Double-fan adhesive binding, which has for the most part replaced oversewing since the mid-1980s, allows volumes to lay flat for good capture without causing damage.

And so much has changed in academic libraries over the last two decades. Libraries have adjusted their collection management strategies for print collections in light of the wide availability of digital content, lower use of print, and demand for the space that print collections have occupied in library buildings.

Information resources lead long lives (if they survive) and their value may change over time, so preservation efforts must be able to meet the needs of current users while keeping the long view in mind. Today, selection for preservation and treatment decision-making both take into account these changing values and uses of the print collections. Envisioning the future value collections may hold, and factoring that into the actions taken today, is a challenging but fascinating part of the work of preservation.

Likewise, the approach to the repair and conservation of research book collections has evolved to support these changing strategies and needs. Advances in techniques have come via cross-fertilization among practices in different conservation specializations.

Traditionally, there was a “partitioning” of responsibilities for the remedial care of books in academic libraries1. Repair of circulating, or “general” collections adhered largely to standardized treatment protocols, or “treatment to specification” as described by Glen Ruzicka2. With this approach, the treatment for an item is selected from a set menu. This provides both consistency and efficiency. By contrast, rare book conservation treatment is customized for each item. Typically, different staff in separately equipped labs applied these two distinct approaches, using different materials and methods.

Also in the past, the high-use, circulating books for which standardized treatments were designed often consumed all the available resources for book repair. At the same time, rare book conservation focused on special collections. Older materials in the general collection sometimes fell between the cracks. This was partly due to their lower priority. But it was also because the procedures and skill sets of general collections conservation labs were designed for modern, case-bound books with strong, flexible texts, not for older binding structures or the kinds of deterioration from which they suffer. Options for older materials may have included deferring action by boxing, or reformatting to preserve intellectual content.

Today, new approaches to book repair, which began percolating in the 1990s, have led to greater integration of general and special collections conservation approaches3. Techniques appropriate for older or “medium-rare” books have become part of the repertoire of general collections conservation today. These methods tend to be more reversible, less invasive, and are often less time-consuming. And some practices from the world of general collections that lend efficiency have been adopted in the work of special collections conservation. So with more tools in the proverbial kit bag, we now have the capacity to address the preservation needs of our collections more holistically.

New Tool in Our Kit Bag — Thread Staples

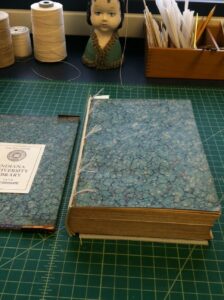

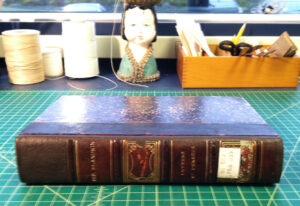

During the MWGBW tour, we showed a variety of techniques used in our lab to solve a common problem of 18th and 19th-century books – detached boards. The attachment fails due to deterioration of the materials, structural design, use, or a combination.

Our repertoire of board re-attachment methods includes Japanese paper hinges, linen tabs, full cloth hinges, cutaway cloth hinges, Ramieband, and one called thread staples.

It is useful especially when you don’t have access to the text block spine, such as in a tight-back binding. It is stronger than Japanese paper hinges, so it can be used on books that are a bit heavier or larger. The first and last signatures need to be well attached.

The thread-staples repair has some things in common with another board re-attachment method called “new slips.” A description may be found in “Binding Repairs for Special Collections at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center,” by Olivia Primanis, published in the Book and Paper Annual, v. 19 (2000). http://cool.conservation-us.org/coolaic/sg/bpg/annual/v19/bp19-30.html

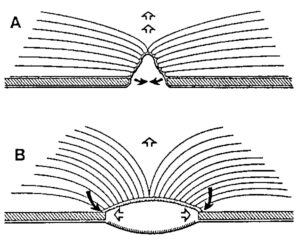

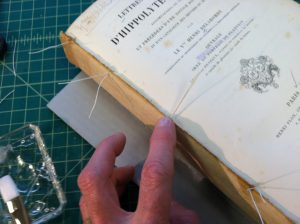

The basic idea for thread staples is that linen thread is sewn through the folds of the first and last signatures of the text block, and the thread tails are used to attach the boards.

Here is a diagram showing how the threads should end up after the sewing is done: one thread tail at the top and bottom, and two thread tails at every other sewing station:

Sewing can begin from the inside of the signature and come out at the point of the shoulder, or from the point of the shoulder on the outside to the inside of the fold, whichever is easiest. It depends somewhat on the depth of the shoulder. If starting inside, you un-thread the needle after the first pass, put the needle back on the thread inside, and then sew through the next sewing station from the inside.

I sometimes rub some thick paste into the threads right at the shoulder and press the tails toward the text block. This helps get the thread to lean in the right direction, but also protects against accidentally pulling the threads out during subsequent steps.

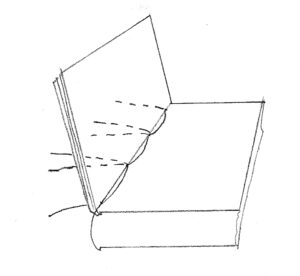

Next the thread tails are trimmed to the length that will fit under the lifted cover material (or paste-down), and then they are frayed out by untwisting the 3 plies first with your fingers, and then using a needle or awl to separate them further.

You should have something that looks like this:

Then the board is positioned on the text block

and the thread tails are adhered under the lifted cover material. The threads are splayed out, and made tight and flat using first a brush and then rubbing down/pushing inward with a spatula.

We enjoyed the visit from the Guild of Book Workers Midwest Chapter, and it was fun sharing some of our work!

- “Integrated Book Repair,” by Gary Frost, Archival Products News, v.7, no. 3, Fall/Winter 1999-2000.

- “Book Repair in Research Libraries,” by Maria Grandinette and Randy Silverman, Abbey Newsletter, v. 19, no. 2, May 1995. http://cool.conservation-us.org/byorg/abbey/an/an19/an19-2/an19-201.html

- “Identifying Standard Practices in Research Library Book Conservation,” Library Resources & Technical Services (LRTS), v. 54, no. 1, 2010, pages 21-39.

Leave a Reply