By Wendy Spacek

Collection Management with a Preservation Perspective

In the fall of 2018 I joined the Preservation Lab as a Student Conservation Assistant. I was excited to engage my skills as a painter, printmaker, and DIY bookmaker to help preserve library materials. At the time, I was in the final year of my MFA in poetry and intended to continue at IU to complete my library degree. I started as most Student Conservation Assistants in the book conservation lab have: removing the staples from music scores and sewing them into pamphlet binders. To some it would seem a tedious job, but I found the meditative, repetitive task relaxing and I was eager to learn more.

For the next year and a half I learned treatments and tricks from everyone who worked in the lab, picking up details about how books are made, why they fall apart, and how books are identified and prioritized for repair or stabilization. By early spring of 2020, I was practicing just about every treatment available to Student Conservation Assistants in the lab. Then suddenly, like many others, everything changed because of COVID and I was no longer able to work in the lab.

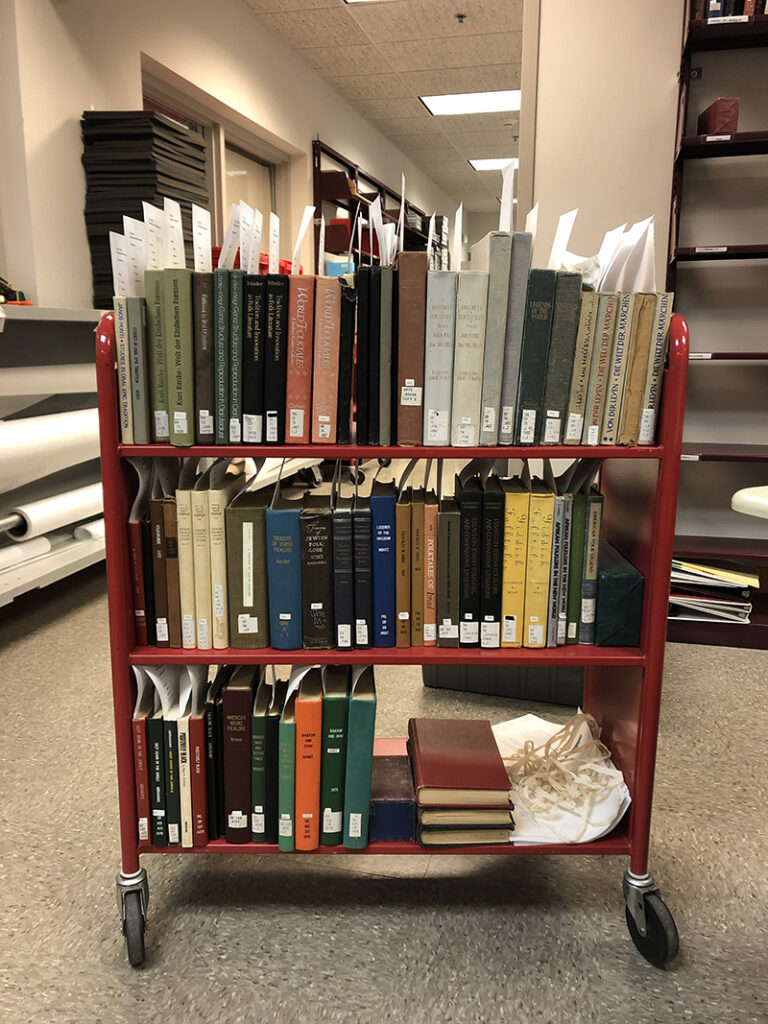

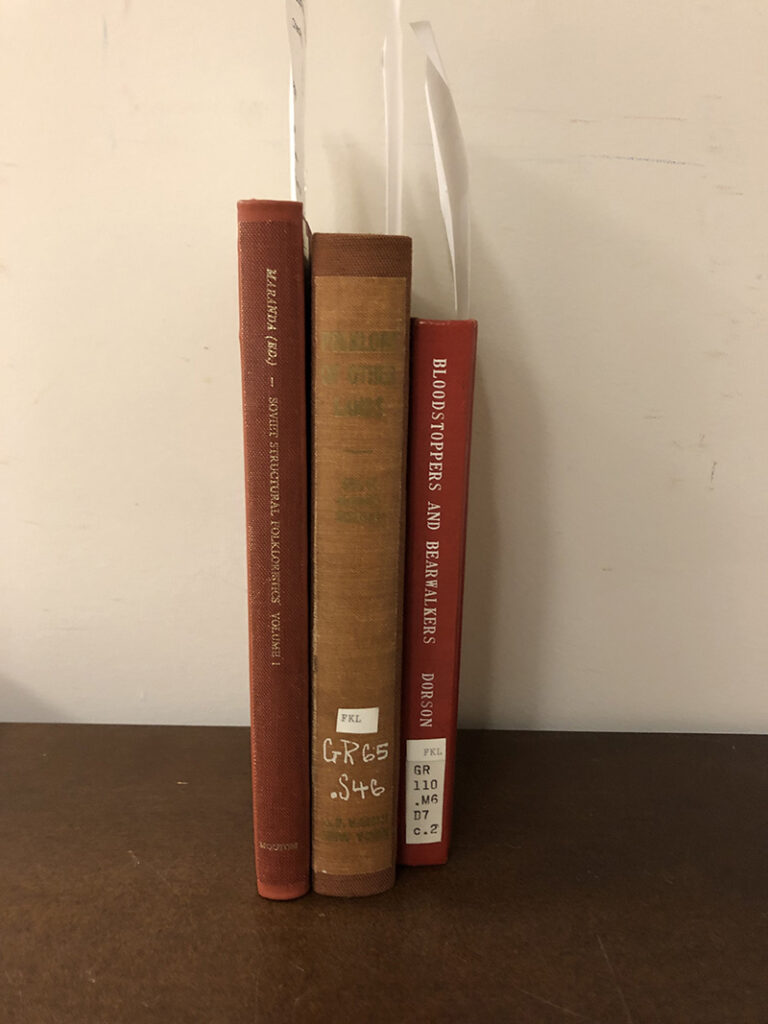

Over the year of quarantine and lock-down that followed, I continued my MLS coursework remotely, leaning into my interests in collection management, research support, and teaching. When vaccinations became widely available in the spring of 2021, I was delighted to be offered the opportunity to return to the lab for the summer to participate in a de-duplication and preservation project for the Folklore Collection; a project designed as a pilot for larger de-duplication and preservation efforts. Working on this project both mobilized and tested my existing preservation knowledge, expanded on my database management skills, and deepened my understanding of library workflows, policies, and procedures.

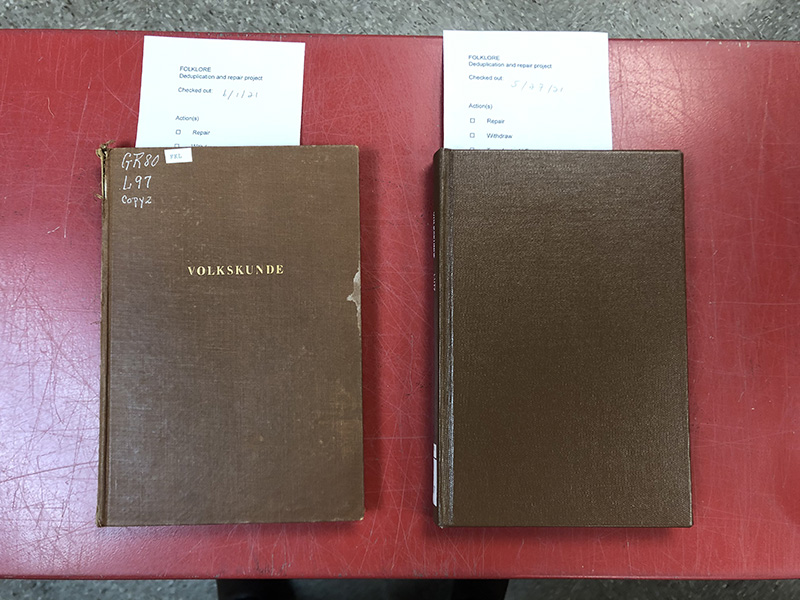

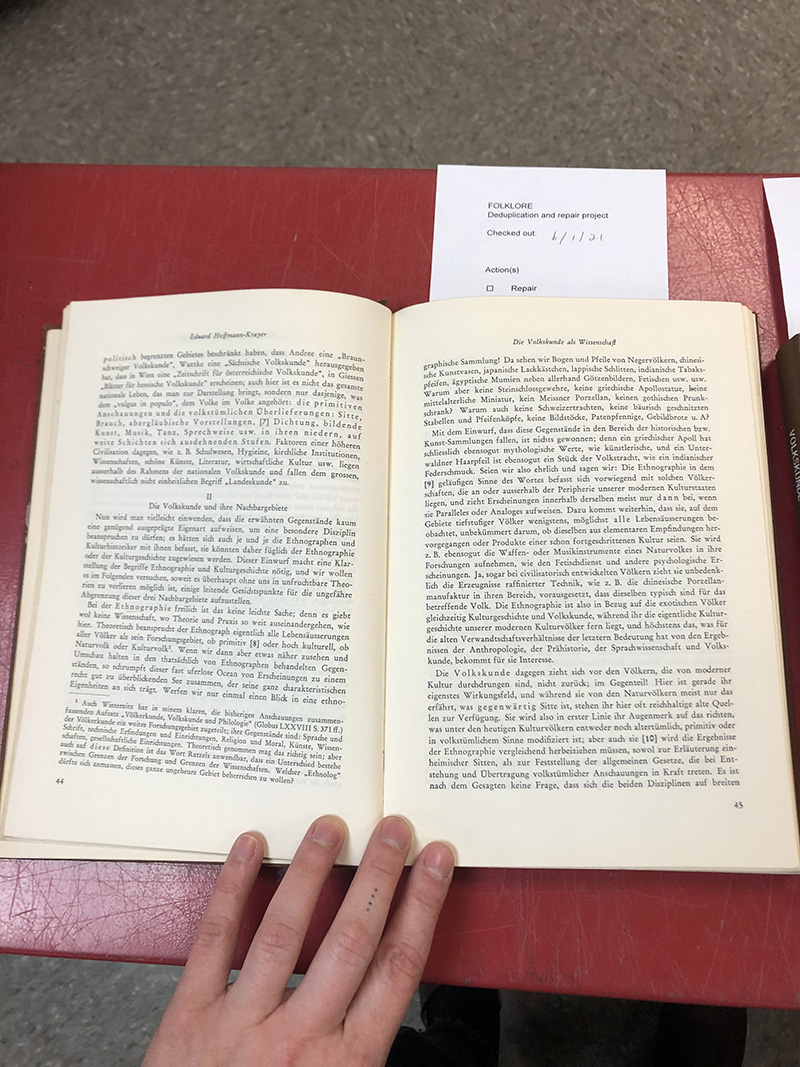

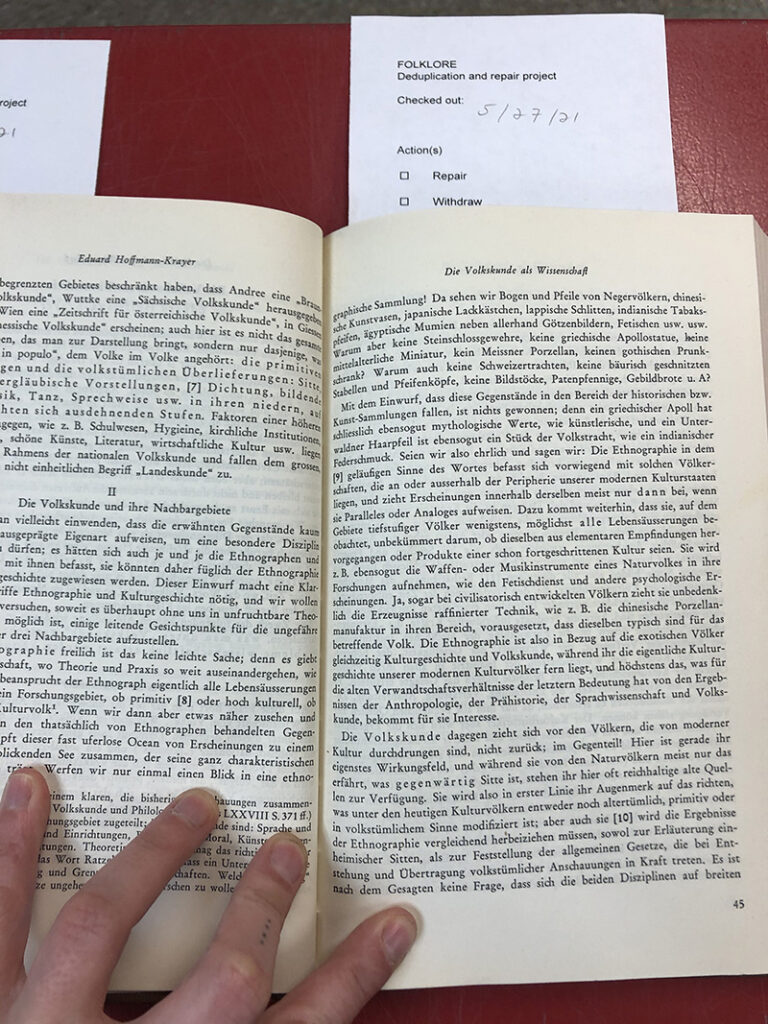

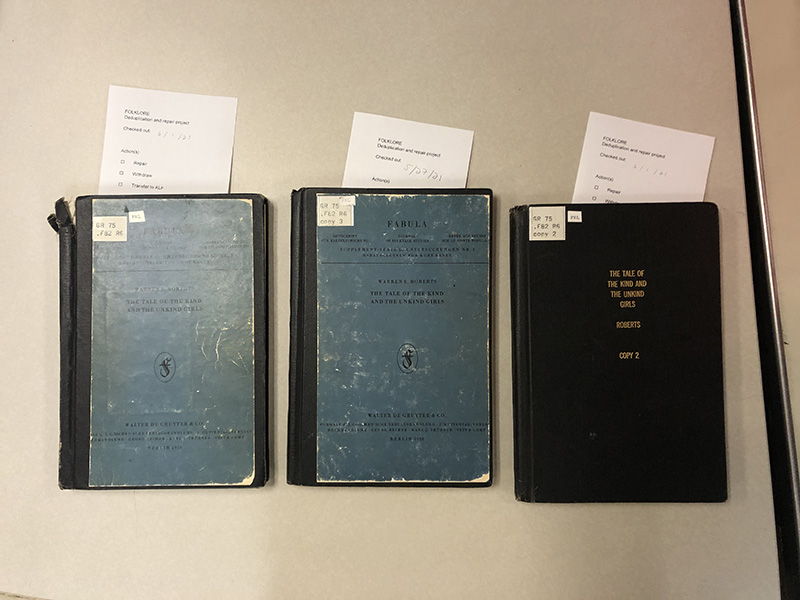

For the next month and a half, hundreds of books passed through my hands. It was my role to look at each set and evaluate them based on how they were made, evaluate prior repairs, and their present condition (see the previous blog on this site, You Can’t Judge a Book by the Cover, which explains a lot of the thinking that goes into such an evaluation).

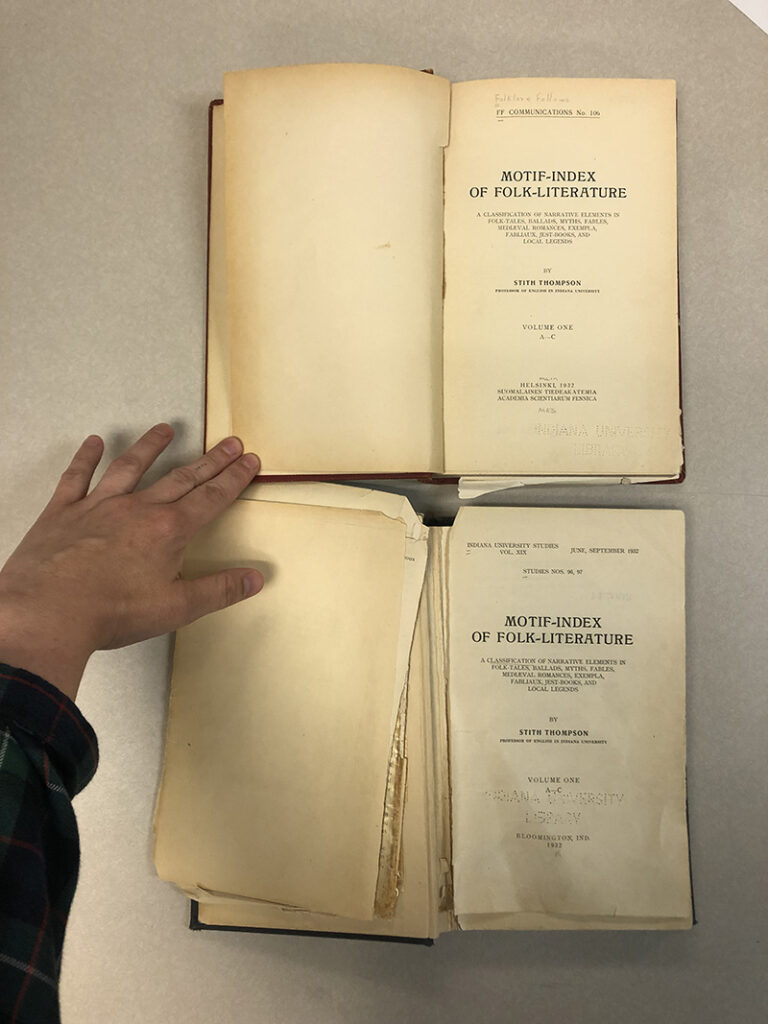

Some sets were easy: a copy sewn through the fold with little wear to the interior or covers was an obvious choice when compared to an over-sewn copy with too-tight binding, and brittle, torn pages.

When these decisions became difficult was when choosing between very bad copies of the same book.

This is where the skills I’d gained in my years as a Student Conservation Assistant really came in handy. Because of my past preservation experience, I could estimate how much time it would take to complete various repairs, identify opportunities for simpler, less-time consuming fixes, or know when to bring the two awful copies to my supervisor for her opinion.

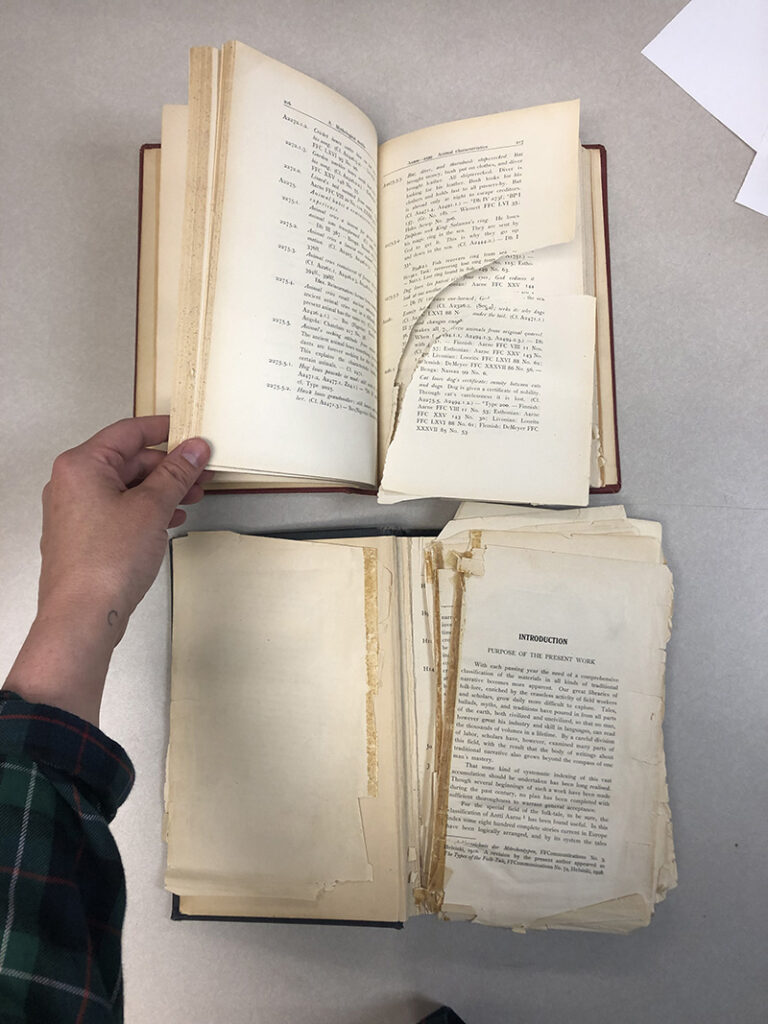

As I worked my way through the project, giving recommendations for repair and turning the books over to the full-time conservation staff, I encountered binding methods I’d not yet seen, books with unidentified substances smeared across their pages, heart-warming inscriptions to beloved professors, and the unfortunate reality of acidic paper gone brittle and crumbling as I turned each page. Through conversations with the conservation staff, I expanded my knowledge of preservation techniques and witnessed how conservators make different decisions based on the item and its needs. There are a number of ways to approach a book in need of repair, and sometimes two conservators will make different decisions, or the same conservator might take a different approach on a different day, due to external factors like overall workload or the skill level of available staff. Like so many things in the library world, there is more than one way to do it! Hearing back from full-time preservation staff about how the treatment they ultimately performed aligned and differed from my recommendation was uniquely instructive, and served to deepen knowledge of book repair techniques and decision-making.

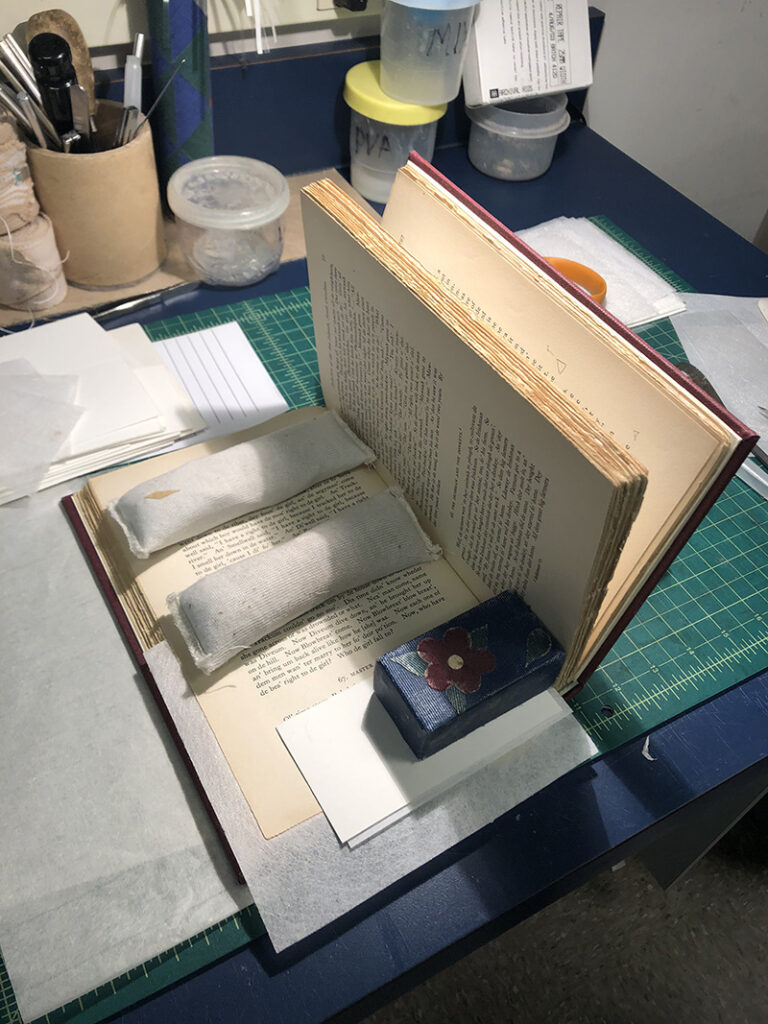

While I worked on the project, I evaluated the condition of over 1000 individual monographs. Beyond the preservation skills I expanded upon, I also deepened my knowledge of library management software, database software, and library workflows and procedures. While evaluating titles I uncovered and flagged numerous cataloging errors, a happy side effect of such a project. Between pulling books in the stacks at Wells, packing totes of books and organizing them on carts, and comparing copies and making recommendations, I read up on preservation management in libraries, and even had some time to make some conservation treatments of my own by mending torn pages with Japanese paper and wheat paste.

This project is a wonderful example of preservation staff and subject librarians working together to maintain the health and continuation of a collection. As I move into my new position as the Arts & Humanities Librarian at Central Washington University I’ll bring with me a theory of collection management that integrates principles of preservation and emphasizes cooperative relationships between public and technical library services, centering responsible stewardship of library resources with the shared goal of ensuring continued access to research collections for decades to come.

3 Comments

Love reading posts about the work so many of us never see! Thanks for this, Wendy!

Very nice work, Wendy. The Folklore Collection is much improved because of your careful efforts on this project–thank you. All the best in your future endeavors!

This was informative! Best of luck, Wendy!