The question of what predictions one can make from political polls has been a hotly contested one this political campaign. Despite the appearance of scientific certainty, who’s ahead in a poll is reliant on the demographic make-up of the polling audience. For example, when Romney was behind in the polls before the first presidential debate his advocates suggested that pollers were under representing his supporters.

Shirley Engle, a former Indiana University professor of education and director of the Social Studies Development Center (SSDC), addressed the issue of what exactly you can learn from polls in his 1969 educational film Making Inferences from Statistical Data, one of the educational films held by the Indiana University Libraries Film Archive and available for viewing online along with several other IU produced films. Okay, not a barnburner of a title and the film itself is rather staid. But stick with me here.

No one said making well-informed democratically-minded citizens was a blast. Though leaning towards the functionally pragmatic in terms of filmmaking – the film is mostly a staged version of a class discussing polls and what they might have revealed about demographics and political beliefs – Engle was working to transform social studies from a rote memorization of facts to a politically engaged subject built off of the concerns and experiences of students.

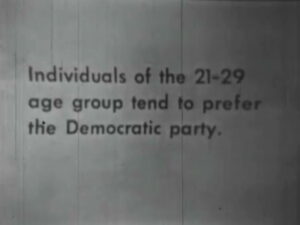

The film was part of a program to train social studies instructors in teaching the subject in this then new progressive manner. This particular module focuses on the limits of reading data. John Patrick, the director of the SSDC after Engle, leads a group of Bloomington -area high school students, all white, through data on how different demographics groups voted in recent elections. The students then attempt to infer whether these different groups were more likely to vote Republican or Democrat. Showing the strong brand continuity of these political parties the general conclusions more or less hold true in 2012. Older people tended to vote Republican while younger generations trended towards the Democrats. Republicans attracted white voters while the Democratic Party was more closely aligned with minority voters.

But what is revealing about this film is the degree to which Patrick attempts to place the students’ findings in dialogue with each other. It might seem like a minor detail, but while he leads the class from one topic to another, it is the students who present the conclusions. Patrick doesn’t tell them what to believe. They analyze the evidence and come to a consensus on the limits of reading into polls.

Engle was greatly concerned that what he termed the “authoritarian school climate” would prevent students from growing into politically active well-informed citizens. To counter that dictatorial pedagogy, this film models a classroom where students come to their own conclusions, but, importantly for Engle, they are conclusions based on a considered reading of empirical data and are tested through group dialogue.

While as a piece of filmmaking Making Inferences from Statistical Data might mirror Engle’s button-downed appearance, the film and its maker were advocating for a transformation in how educators helped students become politically aware. In reading his writings from the time of the film, Engle almost comes off as a political radical despite his moderate appearance of a flattop haircut and grey suit. This gap between the film, created to instruct as clearly as possible, and the more revolutionary approach to pedagogy that undergirds it, point to the necessity in placing these educational films in the theoretical contexts in which they were made.

This is the first blog post in a two-part look at how educational films addressed politics. Tune in next week for an examination of Study of Government.

~Andy Uhrich