Leading up to IULMIA’s June 6 unveiling of the expanded WWII Propaganda Films and IU online exhibit, we’re presenting in-depth posts about three outstanding titles among the many newly digitized war-era films from our collections. The first film in this series of feature blog posts is a 13 minute Kodachrome gem from 1942, You Can’t Eat Tobacco.

Curation of the 84 films in the expanded exhibit has focussed on the uses of government produced informational, educational, and propaganda films in civilian life. Films were selected from IULMIA’s collections of 16mm prints distributed during WWII to school and community groups around Indiana by the University Extension Division’s Bureau of Audio-Visual Aids. Beyond the combat reporting and heavy-handed propaganda intended to mobilize public sentiment behind the war effort, government film production also addressed nearly every other sphere of civilian life, from natural resource conservation to workplace training and educating citizens about the cultures of Allied nations. IULMIA’s expanded WWII Propaganda Films exhibit brings together an extensive collection of these war-era films, representing the great breadth of U.S. Government film production during the conflict.

You Can’t Eat Tobacco is a perfect starting point for taking such an expanded view of wartime filmmaking. The war is neither mentioned nor obviously evident in the world documented, yet the film stands as a strikingly personal and artistically executed work reporting on problems of public health and nutrition resulting from tenant farmers’ economic dependence on cash crops. A clear position advocating reform and improved community health comes across in its brief running time, exemplifying the short form 16mm sound film as a means of educating and informing the public, as a medium for Government to speak to its citizens.

With the film itself offering no more identifying information than this title and the names of the writing and photography team of Margaret T. Cussler and Mary L. De Give, no record on Worldcat, and scarcely anything written about the film turned up in Google searches, excitement mounted at IULMIA at the discovery of this beautiful and apparently rare film. Though it stands on its own as a well crafted, stately work of documentary filmmaking, the story of its creation and its creators is no less interesting.

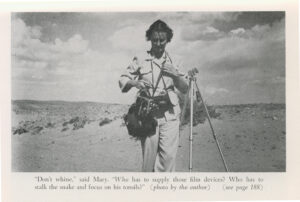

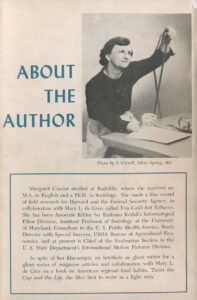

Piecing together the story of this film and its creators has relied foremost on the account given in Margaret Cussler’s highly entertaining memoir Not By A Long Shot: Adventures of a Documentary Film Producer, published in 1951 (in the public domain and available in its entirety at Hathi Trust). Described on the jacket flap as a “lighthearted, firsthand story of two young women who set out on a shoestring to form a film company,” promising the reader that “when two young women step from the college campus to enter into a new audio-visual medium of education and information, you can look for things to happen.” Armed with Radcliffe credentials, government funding, a 16mm motion picture camera, and an abiding love for Kodachrome color reversal film, the team of Cussler and De Give produced You Can’t Eat Tobacco while assigned to conduct an anthropological study of “food habits” in the rural southeast.

In 1940, while both were still doctoral students working under Harvard sociologist Carle C. Zimmerman, Cussler and De Give were sent to a tobacco growing region of coastal North Carolina to study the role of nutrition in the cultural changes of the area. Their study focussed on a place referred to as Seaford, or “a village of 300 inhabitants of the coastal plains area of a southeastern state,” actually Bath, North Carolina’s oldest town, a port located near the mouth of the Pamlico River.

Having seen the study conducted for Harvard, the director of the Federal Security Agency’s National Nutrition Program sent Cussler and De Give back to Bath over a year later to evaluate the effects of the Nutrition Program. The two were sent on by the government to study the contrasting food habits of other areas of the rural south with those of the Bath tobacco country: the “live at home economy” of self-subsistent agriculture in German Flats, South Carolina, and the cotton growing economy in Thomas County, Georgia. The two women’s remarkable fieldwork tour of the rural south in the earliest months of WWII is narrated in charming detail in the first third of Not By A Long Shot. This work also resulted in doctoral dissertations, both completed in 1943 (Cussler’s Cultural Sanctions of the Food Pattern in the Rural Southeast and De Give’s Social Interrelations and Food Habits in the Rural Southeast, see bibliography below).

Bath, N.C., and the surrounding communities of tenant tobacco farmers, became a focus of Cussler and De Give’s work as it exemplified a local economic and cultural food system failing to provide nutrition and health to its citizens. As Cussler would write in her narration of the film, the reliance on a “one crop” system meant that farms weren’t producing food to feed farm families, and the paltry cash yielded by a tobacco crop too often went to store-bought foods of poor nutritional value. From November 1941 through February 1942 Cussler and De Give lived in a boarding house in Bath, observing, photographing, filming, and conducting interviews about local food habits.

In their 1952 book ‘Twixt the Cup and the Lip (also available in full at Hathi Trust), drawn from the cumulative experience of their research on food habits in the southeast, Cussler and De Give reflect on their decision to use filming in their fieldwork, also indicating that they were screening their footage locally in Bath as they worked:

Documentary photography provided a device for securing supplementary data on the physical milieu, and also provided some insights into the social and cultural milieu. Besides a collection of still shots, a movie in color and sound, You Can’t Eat Tobacco, depicting socio-economic factors affecting nutrition in the rural, one-cash-crop South, was produced in the course of these studies. An additional advantage proved to be the entree which photography gave to homes when it was desirable to check the behavioral pattern with regard to food against the ideal pattern. Also, the popularity of local showings of scenes from local movies facilitated continued work in the community.

Shot on 16mm Kodachrome over the course of these four months, using mostly naturally lit outdoor shots with handheld camera, the film has all the apparent spontaneity and unscripted intimacy of a particularly beautiful home movie, yet a striking, serious aesthetic intention in De Give’s composition of her shots. Repeated throughout the film are steady, eye-level portraits, held long enough for each subject to stare back into the camera’s lens. The fieldwork itself required a degree of trust and intimacy, going from farm to farm interviewing mothers about the diet and health of their families. As they note in ‘Twixt the Cup, “working as women with women informants on a topic so closely associated with women’s traditional work appears to have its advantages (…).”

After its completion in 1942 the film appears to have been put into distribution by the New York University Film Library. A 1944 New York City Food and Nutrition Program publication provides this excellent summary:

Poverty, broken lives, disease-ridden people . . . these are all-too-common by-products of the one-crop system throughout the tobacco country of the South. You Can’t Eat Tobacco deals with the evils of this system, then proceeds to illustrate some of the ways in which the impoverished Southern tobacco farmer may improve his lot. The film opens with scenes of the typical broken-down homes and under-nourished families of farmers who plant all of their acreage in tobacco. Raising practically nothing for themselves, these families depend on the “rolling store” to supply them with the sweets and starchy foods which constitute a major portion of their diet. Pellagra is prevalent throughout tobacco-land with patent medicine men and unscrupulous druggists thriving on sales of costly remedies. Tobacco farmers can, however, improve their diet, their health and their income by devoting some of their land to raising food crops and livestock. They can turn to Federal, state and local agencies for assistance in planning and growing foodstuffs and selling their surplus at nearby markets. Local schools can help speed community rehabilitation by developing school lunch programs, by teaching good nutrition and health to parents and children, and by offering instruction in home economics to future farm mothers and classes in farm management to future farm fathers. The county doctor, too, can be encouraged to play a more active role in fighting malnutrition in his locality. Even church meetings and picnics may be used to teach better health through better eating. Thus, through individual and community effort, the one-crop system with its attendant malnutrition and disease, can be banished from tobaccoland forever.

An entry in the 1947 H.W. Wilson Educational Film Guide confirms that the film was generally available for rental, noting “Sequences of special regional interest include: a day in the life of a sharecropper, typical pellagra cases, a Negro church service, the visit of a patent medicine man and teaching in a rural school.”

Circumstances surrounding its distribution by Indiana University are less clear; the print held at IULMIA is dated 1943, yet the title does not appear in the War Films catalog or any of the other Burueau of Audio Visual Aids catalogs published during the War.

After a short stint working on educational films for Eastman Kodak, Cussler and De Give ultimately went on to found their own production company, Social Documentary Films, making at least two more completed films that are known. Not By Books Alone (1945) commissioned by the Rochester, NY, public library, with this summary in the Wilson guide:

How one library serves the citizens of its community in education, enrichment, and recreation, making better homes, earning a living, and intelligent citizenship.

An issue of Rochester History Journal notes that Not By Books Alone was so successful that “the U.S. State Department paid for its translation into several languages and UNESCO screened the film at conferences in Mexico City and Paris.”

Their third and final film, Hopi Horizons (1946) was shot around Arizona reservation communities while Cussler and De Give had temporarily relocated to Los Angeles. IULMIA’s sole Kodachrome print of this film has been judged too delicate for flatbed viewing, and the Wilson guide’s description gives little more detail than IU’s own scant catalog record:

Life today on the Hopi Reservation is presented from the Indian view-point. Aspects included agriculture, primitive methods and introduction of modern farming; handicrafts; economics; health; education; influence of missionaries and others on customs and habits of living. Film provides starting point for further discussion.

We at IULMIA hope to eventually give both of these later films by Cussler and De Give more thorough attention and research – the work of this remarkable independent production team seems too little known and is certainly deserving of study, appreciation and preservation. Anyone with knowledge of Margaret Cussler and Mary De Give’s filmmaking work, other existing copies of their films, their papers, or their descendants is emphatically encouraged to contact IULMIA.

Coming up next in our series profiling educational films from the World War II era: High Over the Borders (1942), Irving Jacoby’s film on North American bird migration, where flight paths “mock the man-made lines by which nations separate themselves,” providing a useful metaphor for a wartime spirit of alliance between the nations of the Americas.

~Seth Mitter

Margaret T. Cussler and Mary L. De Give non-exhaustive bibliography

Cussler, M. (1943). Cultural Sanctions of the Food Pattern in the Rural Southeast. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Radcliffe College (Harvard University).

Cussler, M. (1951). Not by a long shot: adventures of a documentary film producer. New York: Exposition Press. [Full text at Hathi Trust]

Cussler, M & De Give M.L. (1942) Some Cultural Factors Affecting the Nutritional Situation. Nutrition Division, Office of Defense Health and Welfare Services, Federal Security Agency.

Cussler, M. & De Give M.L. (1942). The effect of human relations on food habits in the rural southeast. Applied Anthropology 1(3):13-18.

Cussler, M. & De Give M.L. (1942). Let’s Look It in the Eye. Consumer’s Guide, March 15.

Cussler, M. & De Give M.L. (1943). Foods and nutrition in our rural Southeast. Journal of Home Economics 35:280-282.

Cussler, M., & De Give, M. L. (1952). ‘Twixt the cup and the lip: psychological and socio-cultural factors affecting food habits. New York: Twayne Publishers. [Full text at Hathi Trust]

De Give, M.L. (1943). Social Interrelations and Food Habits in the Rural Southeast. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Radcliffe College (Harvard University).

De Give, M.L. & Cussler, M. (1941). Interrelations between cultural pattern and nutrition. A study of a village of 300 inhabitants in the coastal plains area of a southeastern state. U.S. Department of Agriculture Extension Service, Circular No. 366. [Full text at archive.org]

1 Comment

Fabulous story; valuable to the current interest in food studies as well as film studies.