“Any practice which tends to divide off American citizens is certainly inconsistent with progressive democratic ideals, and must pass.”

It’s been a little over a hundred years since the founding of Kappa Alpha Psi, one of the first fraternities for African Americans, and the organization is still thriving today. Since its founding, the fraternity has been known for its acceptance of all members, no matter their race, religious affiliation, or national origins. Many people might not know that a few dedicated young men of color founded the first chapter of Kappa Alpha Psi right here at Indiana University in 1911. Founder Byron K. Armstrong, among others, sought out a welcoming, friendly environment for the organization of African Americans on campus.

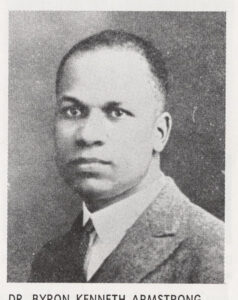

Armstrong was originally from Westfield, Indiana, but attended Howard University in Washington D.C. until around 1910 when he visited his cousin, Irven Armstrong, at the IU campus. Impressed with the educational opportunities given by IU, he and a friend he met at Howard, Elder Watson Diggs, transferred. The two of them were among only ten African American students at IU at the time. White students mostly ignored their presence, and they had few opportunities to gather in recreational groups or sports (any sport that involved physical contact was off-limits). Thus, the concept of a fraternity of their own easily caught interest. They organized Kappa Alpha Nu (a forerunner of Kappa Alpha Psi) in 1911 with Diggs as the permanent chairman (Polemarch), Armstrong the sergeant at arms (Keeper of the Records), and John Lee as the secretary (Strategus). Other founders were Guy Levis Grant, Ezra D. Alexander, Edward G. Irvin, Paul W. Caine, Marcus Peter Blakemore, Henry T. Asher, and George Edmunds. Many of the founders went on to have illustrious careers.

Byron, in particular, completed his Master’s degree at Columbia University by 1914, served as the Dean of Education for Langston University from 1921-1927 and 1931-1935, and continued the spread of new chapters of Kappa Alpha Psi to other campuses. However, there comes a time when every alumni has to order up a copy of their transcript in order to continue with their professional career. Byron ordered his in 1935– the same year he received the Laurel Wreath award, the highest honor given by the fraternity– only to be unpleasantly taken aback by the words “colored student” printed onto it.

The archives are in possession of the President’s Office correspondence from 1913-1937, which contains the exchange between Armstrong and the office.

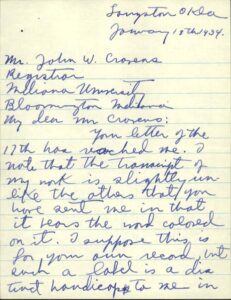

It reads:

Your letter of the 17th has reached me. I note that the transcript of my work is slightly unlike the others that you have sent me in that it bears the word colored on it. I suppose this is for your own record, but such a label is a distinct handicap to me in many [cases]. I am therefore asking that in the future you please leave this notation off since it was not on the original.

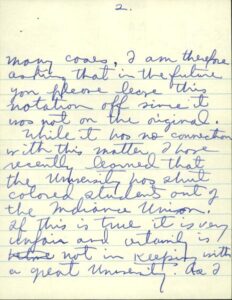

While it has no connection with this matter I have recently learned that the University has shut colored students out of the Indiana Union. If this is true it is very unfair and certainly is not in keeping with a great University. As I am always loyal to Indiana I hope that the day will come when the University can once again return to the ideals of a great democratic University.

The response from the President’s Office indicated they believed they had good reason to keep “colored student” written on the transcript, but did not address his second concern at all.

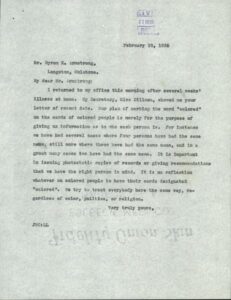

I returned to my office this morning after several weeks illness at home. My secretary, Miss Dillman, showed me your letter of recent date. Our plan of marking the word ‘colored’ on the cards of colored people is merely for the purpose of giving us information as to who each person is. For instance we have had several cases where four persons have had the same name, still more where three have had the same name, and in a great many cases two have had the same name. It is important in issuing photostatic copies of records or giving recommendations that we have the right person in mind. It is no reflection whatever on colored people to have their cards designated ‘colored’. We try to treat everybody here the same way, regardless of color, politics, or religion.

Not entirely satisfied with that response, Armstrong wrote again:

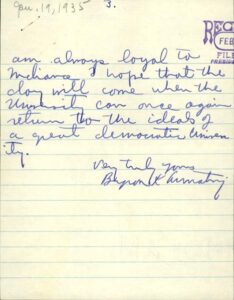

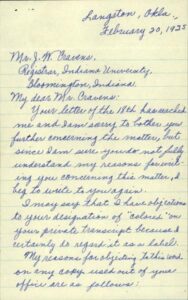

Your letter of the 18th has reached me and I am sorry to bother you further concerning the matter, but since I am sure you do not fully understand my reasons for writing you concerning this matter, I beg to write to you again.

I may say that I have objections to your designation of ‘colored’ on your private transcript because I certainly do regard it as a label.

My reasons for objecting to this word on any copy used out of your office are as follows:

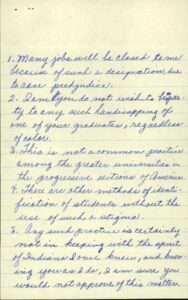

1. Many jobs will be closed to me because of such a designation, due to race prejudice.

2. I am sure you do not wish to be party to any such handicapping of one of your graduates, regardless of color.

3. This is not a common practice among the greater universities in the progressive sections of America.

4. There are other methods of identification of students without the use of such a stigma.

5. Any such practice is certainly not in keeping with the spirit of Indiana I once knew, and knowing you as I do, I am sure you would not approve of this matter.

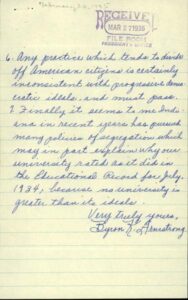

6. Any practice which tends to divide off American citizens is certainly inconsistent with progressive democratic ideals, and must pass.

7. Finally, it seems to me Indiana in recent years has pursued many policies of segregation which may in part explain why our university rated as it did in the Educational Record for July, 1934; because no university is greater than its ideals.

Armstrong wouldn’t stand for being racially stereotyped by his future employers, although it is unclear whether IU granted him new transcripts without the “colored student” indicator or not. In my previous article about mathematician Elbert F. Cox, I mentioned that he had the same indicator on his transcripts, though he ordered his earlier than this one for Armstrong. We don’t know precisely when IU stopped including that on their transcripts; our guess would be around the student population boom following World War II.

But Armstrong couldn’t be held back from success. He went on to earn his doctorate in philosophy from the University of Michigan, and taught in several states around the country. Kappa Alpha Psi still thrives today, and credits Armstrong as a founder on its web site.

1 Comment

Wonderfully done. As your article demonstrates, tImes have been tough over the years and continues today. I am perpetually optimistic, however.

I am a member of Kappa Alpha Psi, initiated af Nu chapter, spring 1962 (Indianapolis affiliated colleges at the time). Graduate of Butler University, Indianapolis Indiana, BS pharmacy 1965 and Indiana University Medical school 1973. The chapter is now at Purdue University, Lafayette, Indiana. I am active in the Baltimore alumni chapter at this time, the Benchmark Chapter.

Thanks Andrea. Will share with fraternity brothers.

Carlton Greene, MD