By Doug Sanders, Paper Conservator, IU Libraries Preservation

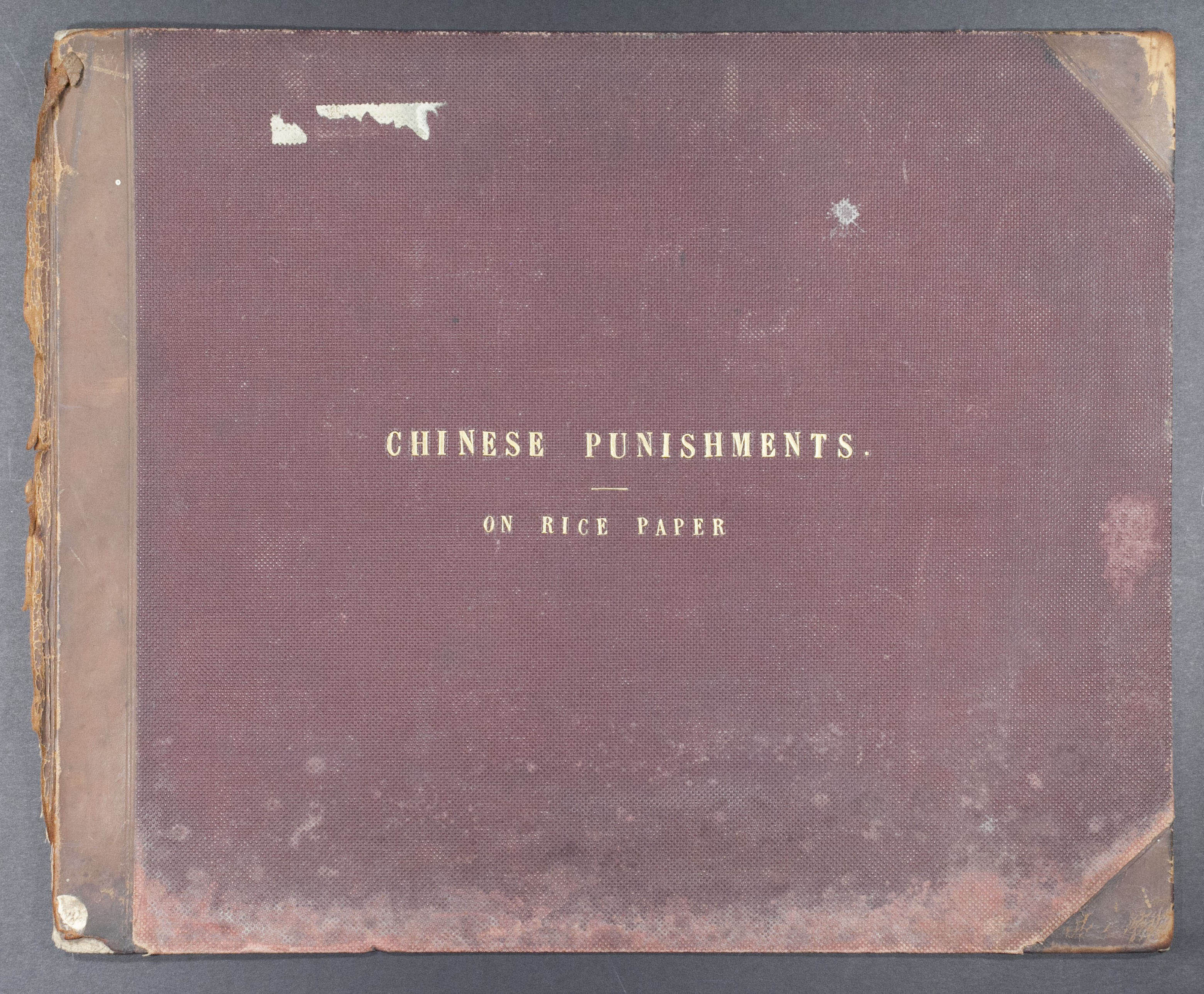

The Paper Conservation unit of the IU Libraries E. Lingle Craig Preservation Lab recently treated a series of paintings from the Allen Mss. Collection at the Lilly Library. These 28 paintings arrived in a loose stack, water damaged, tattered and sooty and in need of repair. Accompanying the paintings was the front board and endsheet of a portfolio that likely held them in the past. On it were the words “Chinese Punishments. – on rice paper” tooled in gold.

The paintings depict various tortures and punishments of criminals, often graphic in nature, done in water-based opaque paints on a paper of Chinese origin (though likely not made of rice). Broadly speaking, these works are termed Export Art, which although sometimes used pejoratively, nevertheless reflects an interesting period in time.

Though they vary in size, each painting is roughly 10 x 13 inches. It is difficult to date them based on stylistic traits or media- these sorts of works were created by workshops in coastal cities of China in often production-line settings, with designs changing very little over time. My best guess is the end of the 18th century, but maybe well into the 19th.

After each painting was photographed and given an arbitrary working number and title, we began the treatment by surface cleaning as much as practically possible, given the fragile nature of the paper with its numerous tears and creases prior to an initial round of humidification and pressing. Humidification (ie. very careful introduction of moisture) allows us to open up fragile creases and then press them to restore the paper to a more planar state. If cleaning is not done beforehand, one runs the risk of water turning fine soot deposits into an ersatz ink and working it into the paper support.

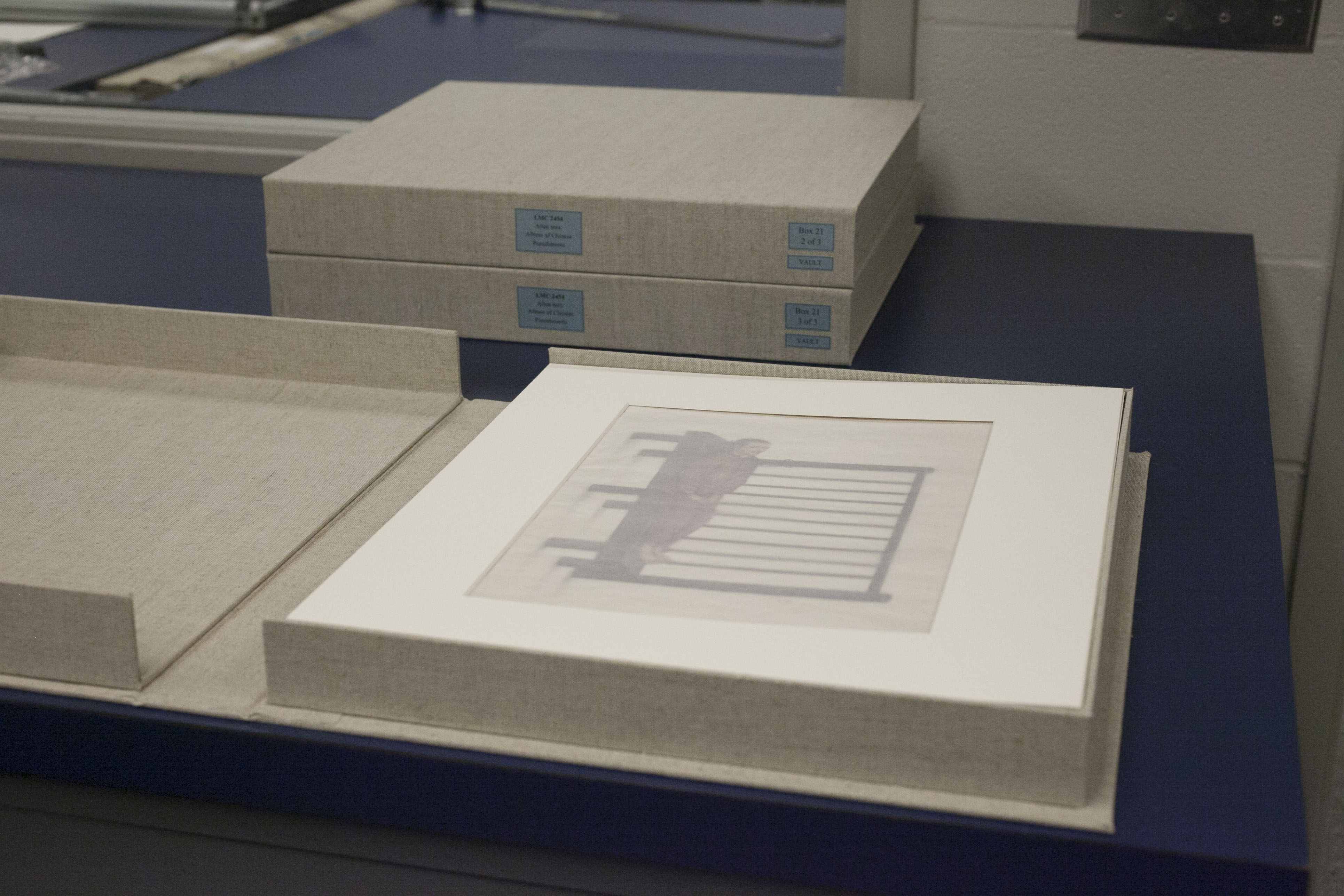

After pressing and cleaning, we could take a closer look at the condition of the items. It was observed that the paper itself did not suffer much from discoloration or heavy staining. That, combined with the water-soluble nature of some of the colors used, led this conservator to decide not to wash the paintings further, but instead move on to repairing the tears to allow for safer access and handling. Because of the translucent nature of the thin paper, conventional mends with wheat starch and light-to-medium weight Japanese repair tissues would have shown through to the front when viewing. Instead, we used a very light tissue pre-coated in the lab with an adhesive called sodium carboxymethyl cellulose. It was reactivated with water and applied to the backs of the works, for an almost invisible mend. After mending, we were able to follow with another course of surface cleaning now that the paper had been strengthened, as well as another round of humidification and flattening. Application of hinges and storage within window mats and custom constructed clamshell boxes completed the treatment.

Interestingly, one side treatment that was performed on several paintings involved the chemical ‘reversal’ of darkened lead white paint as these before and after photos show.

While working with these paintings we began to wonder about their creation and the audience for which they were painted. After all, torture scenes are not something one generally wants to frame and hang over the mantel, and most export art of this time featured quaint scenes of peasants involved in industry, people sipping tea extolling Confucian virtues, or lovely bird and flower pairings. Some time spent online revealed that these very images (well, probably not our set, but identical ones from the same workshop) were used to generate English engravings of the same scenes published in 1801 as “The Punishments of China” by George Henry Mason.

The pieces began to assemble to reveal a very interesting exchange between East and West occurring around this time in the port cities of China. Western merchants and military personnel would dock in these ports and buy artwork to take back home. The Chinese artists found that certain images would sell better than others, particularly those that reflected what Westerners felt China should look like as well as their tastes and styles. Combine this with a growing movement seeking prison reform and changes to criminal justice systems in England and France at the time, and we can see how torture imagery could become a popular seller. A fascinating delve into this period can be found within the book “Death by a Thousand Cuts,” by Brook, et al., which examines Western views and interpretations of the Chinese legal system during the late Qing Dynasty. In it, the authors state that Mason “advised the reader that he had been careful not to include pictures that could be thought of as ‘committing an indecorous violence on the feelings.’” Indeed, the 1801 edition lacks the content of several illustrations that our precursor contains- notably bare buttocks and female frontal nudity. Mason’s volume was produced from images that weren’t purely Chinese to begin with, and then manipulated in such a way through a team of engravers and additional text commentary to produce a product suited to Western audiences of the time. Research reveals such imagery continued to have use well into the 20th century to justify goals of American, European and Japanese foreign policy.

It is not often that we delve into the background of a collection item so thoroughly, as library conservators, but when we do, fascinating stories reveal themselves.

3 Comments

Such a rare and historical Chinese artwork showing the punishments of criminals.

extremely valuable blog. thanks for the sharing

What a splendid article! I read it with pleasure and interest. Please post more!