By Edward O’Shea, Emeritus Professor of English, SUNY Oswego, Author: Seamus Heaney’s American Odyssey

Many readers know Seamus Heaney (1939-2013) as an Irish poet who wrote about the “Troubles” in his native Northern Ireland. Or they may have heard him read his work at a poetry reading, since for over 40 years he crisscrossed the U.S. reading at American universities, not just major American universities but some of the smallest colleges in the country. Fewer readers know that Heaney was a major translator of classical Greek, Roman, Gaelic, and European writers. In fact, Heaney’s Translations, just published, comprises 500 pages. Most prominent in the new edition is Heaney’s translation of the Old English epic, Beowulf, and it was one of the most popular of his books.

Heaney studied Old English at the university, but he didn’t have the competence or the assurance to embark on a translation for university study of that poem. When he was first approached by Norton Publishing to do a new more poetic verse translation to replace the prose version of Beowulf in the venerable The Norton Anthology of English Literature, Volume 1, it was with the gentle stipulation that he take on a “minder,” that is someone with academic professional competence in Old English.

That “minder” was to be Alfred David (1929-2014), Professor of Chaucer and Medieval Studies, but with the ancillary competence in Old English, at Indiana University since 1958. David, who retired in 1994, was also the editor of the medieval section of the Norton anthology.

Heaney’s and David’s professional but increasingly collegial and fraternal collaboration is recorded in the David mss. 1996-2008 in the Lilly Library Special Collections. The collection consists of correspondence not only between David and Heaney but also between other notables involved in the Beowulf translation, such as the Norton editor Julia Reidhead and the distinguished critic and Norton editor Meyer (M.H.) Abrams.

For a period of time and before email became the dominant mode of written communication, Heaney especially developed a fondness for the fax machine. So, he would often compose a letter in the usual way and rather than dropping it in the mailbox, he would fax it to his correspondent. Most of David and Heaney’s correspondence consists of faxes, usually between Bloomington and Dublin where Heaney lived most of the year. During the heaviest period of faxing, David would work over drafts and later proofs of the translation in the midwestern time zone, and the next morning Heaney (or his family) would find the fax machine had disgorged overnight, and Heaney began his next round of responses. The fax machine was so important to Heaney that it is now ensconced in the Seamus Heaney “museum,” actually called the “Home Place’ in Heaney’s birthplace, Bellaghy, in Northern Ireland.

David’s “suggestions” (and he always approached his role modestly and not intrusively) were often technical or mundane, but sometimes more momentous, as when he kept Heaney from making a major translation mistake for lines 2163-4, confusing Hygelac as the agent of a gift rather than Beowulf, mistaking one major character in the translation for another. Amusingly, he advised Heaney against using the word “senior” in line 1786. Heaney had proposed the phrase “senior man’s instruction for him to sit” but David wrote back: “Unfortunately ‘senior’ in America calls to mind ‘senior citizens’ who get ‘senior discounts and other concessions for ‘seniors.” Heaney, in deference for the American audience changes “senior “to “old man.” These suggestions allowed Heaney to produce a translation that would hold up to the high standards of and Old English specialist as well as a more poetic reading for a wider audience of students and general readers alike.

David, writing to Heaney, encapsulates his role this way:

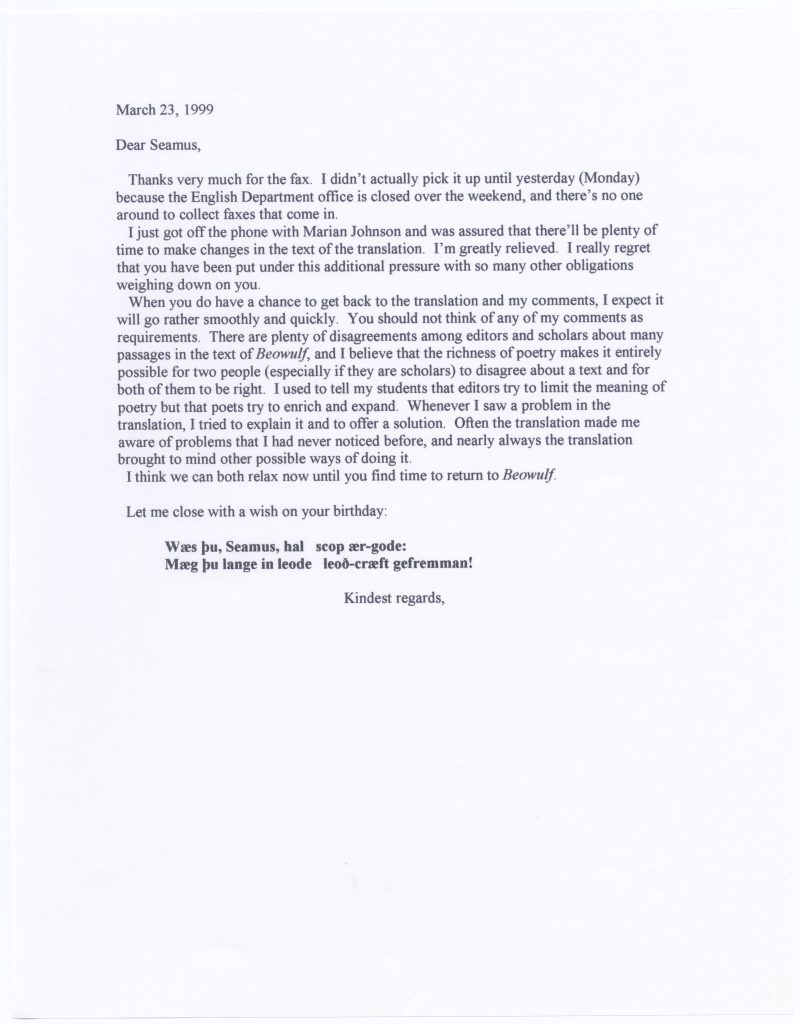

You should not think of any of my comments as requirements. There are plenty of disagreements among editors and scholars about many passages in the text of Beowulf, and I believe that the richness of poetry makes it entirely possible for two people (especially if they are scholars) to disagree about a text and for both of them to be right. I used to tell my students that editors try to limit the meaning of poetry but that poets tried to enrich and expand. (March 23, 1999)

At the end of the fax, David sends Heaney his first birthday wish in Old English:

Wǣs Þu, Seamus, hal scop ǣr-gode:

Mǣg Þu lange in leode leoð-crǣft gefremman!

(Be well, Seamus, preeminent poet:

May you long practice the art of verse among the people!)

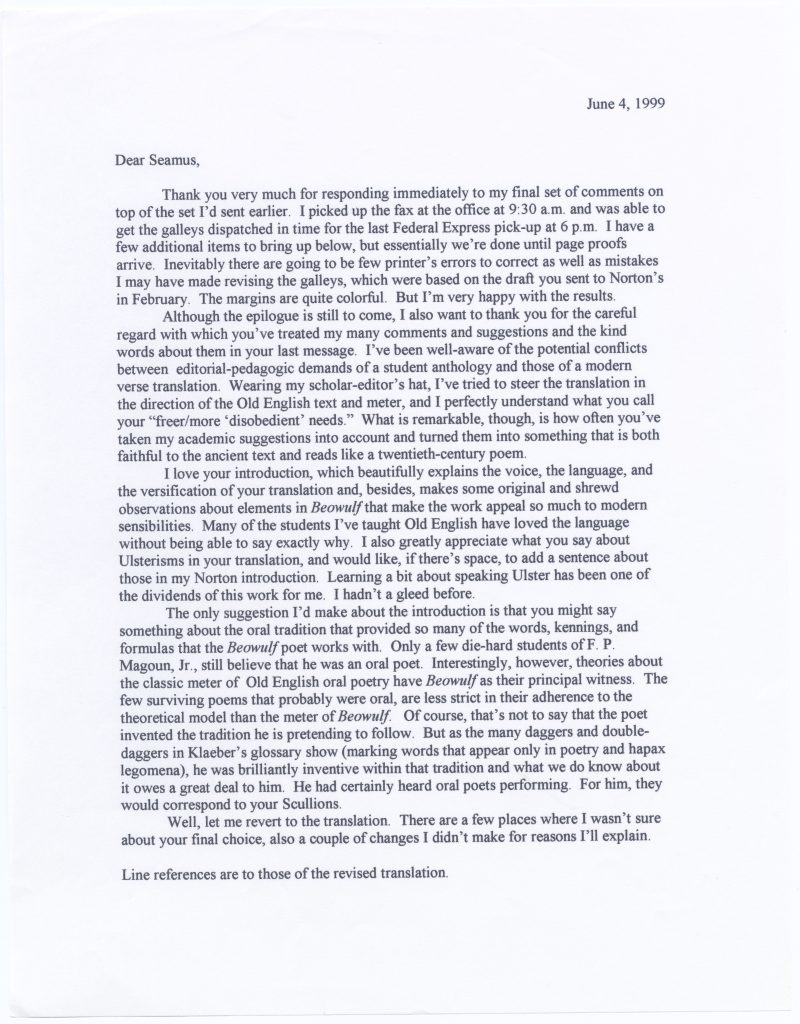

Towards the end of their collaboration, Heaney wrote to David: “I feel there should be some form of epilogue spoken at this point but then remember that we have proofs to go before we sleep….” David replied more expansively to Heaney:

Although the epilogue is still to come, I also want to thank you for the careful regard with which you treated my comments and suggestions and the kind word about them in your last message. I’ve been well aware of the potential conflict between editorial-pedagogic demands of a student anthology and those of a modern verse translation. Wearing my scholar editor’s hat, I’ve tried to steer the translation in the direction of the old English text and meter, and I perfectly understand what you call your “freer more/ ‘disobedient’ needs.” What is remarkable though he is how often you have taken my academic suggestions into account and turned them into something that is both faithful to the ancient text and reads like a 20th century poem. (June 4, 1999)

Heaney’s Beowulf translation was a major international publishing venture with a British publisher (Faber & Faber) and two American publishers ( Farrar, Straus, and Giroux and Norton). Consequently, there were others who advised Heaney, though the final achievement was his alone. Nevertheless, Alfred David of Indiana University was the best kind of editor, playing a major and somewhat unacknowledged role in making Beowulf a respected scholarly text while Heaney made it a poetic text.

2 Comments

Fascinating, and how odd to think of this sort of cooperative work being done in modern times, but before the age of email!

Thanks to the Lilly and especially Isabel Planton for helping me let readers know of this wonderful collaboration by your Alfred David and Seamus Heaney

All your staff have been incredibly professional and helpful and bringing my book to publication.