The first step to transforming roughly 200 boxes of correspondence, typescripts, royalties, scrapbooks, photo albums, gin glasses, dioramas, typewriters, and the many other physical representations of Barbara Mertz’s life and career into a usable and accessible archival collection was to find space for them. It can be hard to conceptualize the sheer size of a collection when you’re looking at a finding aid or other intellectual representation of an archive, so seeing all the materials together in the various spaces I had poached (including two unused cubicles) was a concrete reminder of my task: to somehow organize the physical embodiments of Mertz’s rich, well-lived, and incredibly productive 86 years of life into a narrative.

Processing an archival collection, from deciding which series an item will join to naming the collection itself, is a series of choices that the archivist must make; no two archivists would process the same collection in the same way. This is not to say that there aren’t standards and best practices to follow (The Society of American Archivists, or SAA, periodically updates and publishes their Describing Archives: A Content Standard for free online); however, these standards must be broad in order to accommodate the unique materials and needs of every archival collection, each of which represents the physical remains of a person’s lived experience. Far from being neutral or passive, archival processing is the archivist’s attempt to recreate the narrative of a human life through material objects, thus imposing order onto chaos both physically and intellectually. There are no correct processing choices; so long as the archivist’s choice is justified and preferably reversible, it is a correct choice for the collection. To gather the information necessary to form a justified choice, the archivist undergoes the first two stages of the processing workflow: Research and Survey.

While calling it a “workflow” makes it sound linear and straightforward, the reality is that many of the stages will happen repeatedly and often simultaneously throughout the processing of a collection. For example, while I learned in my initial research that Mertz had named her estate MPM Manor to incorporate her three pseudonyms (Mertz, Peters, Michaels), I didn’t figure out that MPM was also the title of her self-run newsletter until I came across a cache of them while surveying the contents of a box, thus necessitating further research into what it was that I’d found and restarting the cycle.

This brings me to my next step in our Mertz processing journey: opening every single box to make a preliminary inventory of its contents and better understand the types of materials in the collection (the “survey” stage). This process was made significantly easier by the existing organization and labeled folders of the materials (which was at least in part due to the organizational prowess of Mertz’s assistant and friend Kristen Whitbread, I learned later). While the sheer amount of material made synthesizing a larger picture of the collection a challenge, it was certainly more straightforward with folder titles like “Falcon typescript” and “Stupid MWA Thing” than, say, several linear feet of papers dumped into a trash bag with no semblance of identification or order – which is how I received another archival collection which I will not name. However, the frequent use of abbreviations or character names to identify folders as well as the breadth of material types, including a box simply labeled “helmet (FRAGILE)” that ended up containing Mertz’s pith helmet, meant that I had to circle back to the “research” stage for context and elucidation. Part of this process involved creating a complete list of Mertz’s published works, which revealed my first obstacle: how would I organize Mertz’s 72 works across three pseudonyms in a way that both adequately reflected the complex layers of her professional life while also providing an accessible structure for researchers and patrons? I decided to divide her works into her three pseudonyms, and within those pseudonyms I organized them chronologically in an attempt to mirror her writing trajectory. This required me to create a bibliography of Mertz’s work, partially so I could identify shortened titles (such as a folder labeled “Ape,” which contained materials related to The Ape Who Guards the Balance) but also to arrange the works chronologically once I began physically rearranging the collection. This was also the stage where I began to deeply research Mertz’s personal and professional lives.

Born Barbara Louise Gross in Canton, Illinois, Barbara Mertz (1927-2013) was an American author and Egyptologist. While her two non-fiction works on ancient Egypt are highly regarded in the field, Mertz is best known for the gothic and supernatural thrillers she published under the pen-name Barbara Michaels. As Elizabeth Peters, a pen-name created from the names of her two children, she wrote the extremely popular Amelia Peabody mystery series, which follows a Victorian Egyptologist, along with two other mystery series following memorable heroines: professor of art history Vicky Bliss and librarian Jacqueline Kirby. An avid gardener, cat enthusiast, lover of gin, and collector of vintage jewelry, furniture, and clothing, Mertz was also highly active in the professional development of writing and Egyptology throughout her career. In 1989, Mertz helped found Malice Domestic, a professional organization dedicated to traditional and cozy mysteries. Mertz also served as president of the American Crime Writer’s League (ACWL) for a time and served on the Long Range Planning Committee of the American Research Center in Egypt (ARCE) from 1997-1999. In 1991, Mertz established the Elizabeth Peters-Barbara Michaels Scholarship at Hood College for students of color interested in pursuing a mystery writing career.

![Typed contract titled “Heidi Ho Cattery – Purchase Contract” with the following text: “I. Breeder’s Guarantee: 1. I guarantee this kitten [handwritten note that reads “smoke-torti, female, born 1 Sept. 70” here] to be in bood health at the time of purchase. He has been fully immunized against feline enteritis and pneumonitis. He has been checked for worms and found negative, but was given two precautionary wormings for round-worm prior to sale. He has no fleas, ear mites or other external parasites. 2. I further guarantee that should this kitten become ill with or die of any hereditary defect within the first two years of life, I will refund the full purchase price, providing the following conditions are met: a. The kitten was treated by a competent veterinarian. B. The buyer presents a statement from the veterinarian as to the true cause of the illness or a post mortem report as to the cause of death. 3. I agree to assist the buyer with any problems he/she may have regarding the care, feeding, and training of this kitten, and will if space in my cattery permits, provide emergency boarding facilities for the kitten providing he is in good health and has up to date immunizations against enteritis, pneumonitis and rabies. 4. I will assist the buyer in finding a suitable home for this kitten should it become necessary for him/her to give the cat up for adoption. Mary M. Condit, Breeder”. Handwritten note at top of paper with the following text: “Tabitha b. 1970”. Handwritten note at bottom of paper with the following text: “(“Connie” Condit)”.](https://blogs.libraries.indiana.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Adoption-paperwork-for-cat-797x1024.jpg)

As I surveyed the collection, I also sorted out the books and book-like objects to be catalogued rather than archivally processed (the “conservation/removal” stage). The differentiation of book-like objects from archival materials can be muddy and defy any limitations you attempt to impose. For example, while you may say a “book” is any item that is bound, I would argue that a bound journal is part of an archival body of material rather than a book-like object. The decision, for me, comes down to whether the item’s value lies more in its inclusion of a body of materials or in its individual, standalone contents and physicality, which is also how I conceptualize the difference between archival processing and cataloguing. This is, of course, an oversimplification, as books are not isolated objects and their larger collections and contexts are equally as important as those of archival objects. Rather, it is a matter of how archival description takes a top-down approach by grouping items into a collection and then subdividing into series and subseries, while cataloguing emphasizes individualized description of items and then places them within the context of their history and provenance. After removing everything I determined should be catalogued rather than processed, I ended up with 168 boxes and tubs, along with a rough idea of the series (a fancy word for “group of materials of the same type or theme”, such as “correspondence” or “photographs”) I would use to organize their contents. Now that we’ve got the archival theory out of the way, I can dive into a series-by-series exploration of my eight-month journey through the Mertz collection and all of the wonderful things I discovered and learned.

Mertz/Peters/Michaels In typical archivist fashion, I’m starting off by immediately breaking the “series-by-series” structure I established by discussing the first three series of the collection at once. However, the artificial division of one woman’s three identities was difficult enough to pull off in the collection and I refuse to revisit the same challenge in this blog post. These were the most straightforward series to organize, as their contents were already intellectually separated by the published work to which they related. I chose these three as the first series partially because I wanted to place Mertz’s writing career front and center, but also partially because it was the most straightforward and largest grouping of materials. Once I start physically rearranging materials (a combination of the “series” and “arrangement” stages), I typically use a method I call “piling,” which is what it sounds like: creating literal, physical piles of items grouped together by series or subseries (a grouping within a series). Since I didn’t have the space, patience, or balance to physically pile 168 boxes’ worth of materials, I used my preliminary inventory to determine which boxes held materials relating to the subseries I was working on. Again, this sounds much more straightforward than it is; I spent many hours deliberating over whether to group all the Amelia Peabody books into an “Amelia Peabody” subseries within the “Elizabeth Peters” series, with each published work as its own sub-subseries, or whether that imposed too much artificial structure and I should just toss them all together on the same hierarchical level. I continued to find materials that belonged in these first three series up until the very last box I processed, causing much frustration as I either had to plug these later items into an earlier series, throwing off my perfect box chronology, or physically rearrange 140-plus boxes.

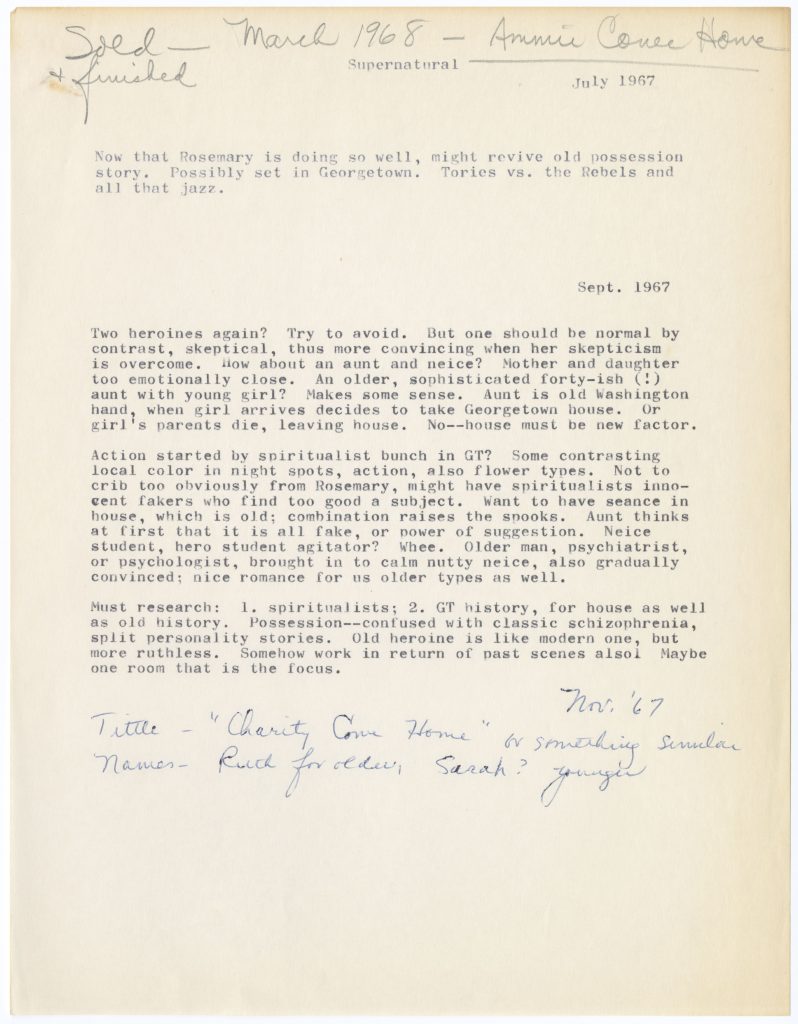

As I processed these series, a pattern of materials emerged that seemed to illustrate Mertz’s writing habits: each book had a one-to-two page synopsis, a number of edited and revised typescripts, and often a folder (or more) of research, especially for the historical romances. Not only was the research material fun to read through, but it also illustrates how thorough and dedicated Mertz was to accurately creating rich, full worlds for her heroines to inhabit, as well as the sheer range of settings and themes her work explored, from sixteenth-century German woodcarving to the American Revolution. Because much of the research could apply to a number of her works (her research files on Egypt, for example, could apply to any of the Amelia Peabody books as well as some of the Vicky Bliss books and Mertz’s nonfiction Egyptology works) and was thus difficult to slot into one particular book’s sub-subseries, I ended up creating a Subject File series later on that grouped these materials by subject – more on that later. The plot synopses were one of my favorite parts of these series, as they highlighted both the immense thought and planning Mertz put into every one of her works as well as her biting wit and sense of humor.

![Typewritten paragraph on yellowed paper with the following text: “1976 Michaels // For the bicentennial, of course. Set in Williamsburg and Alexandria. The heroine has something to do with the Wmsburg commiccion. Must write to them. Archaeology, design, folk art? Or does she have a relative who has willed his house to the commission? Does she fall in love with a ghost? Ho ho.” Written in blue pen at the top of the page is the following text: “’Patriot’s Dream’ sold to Dodd Mead 1975 – publ. 1976’”. Written in red under the typewritten paragraph is the following text: “Nothing so simple. Transmigration of souls. She “remembers” several other lives in Wmsburg. First during Revolution – she is in love with a Britisher.* Second, in Civil War – a slave! Who is the son of her fiance’s father* - Third? In all cases, she fails to fulfill her destiny thru cowardice and failure of L-O-V-E. Now her re-born soul is getting another change – use flashbacks, considerable historical detail – she re-lives parts of these lives – stress brotherhood of man, equality of the soul in the cosmic order, etc. – [illegible] comes when it turns out she is not even descended from the family but adopted? The mystique of the blood a humbug. Have them meet bloody ends, or simply leave for a new life without her? – latter more sensible, former more dramatic – “One with all the men and women who ever dreamed of a kinder, better life for all their brothers – the founders of a dream, which persists thru rended history, however tarnished and bothered”. Written in pencil beneath this is the following text: “I can’t get involved in this. Try again.”](https://blogs.libraries.indiana.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Patriots-Dream-plot-outline-794x1024.jpg)

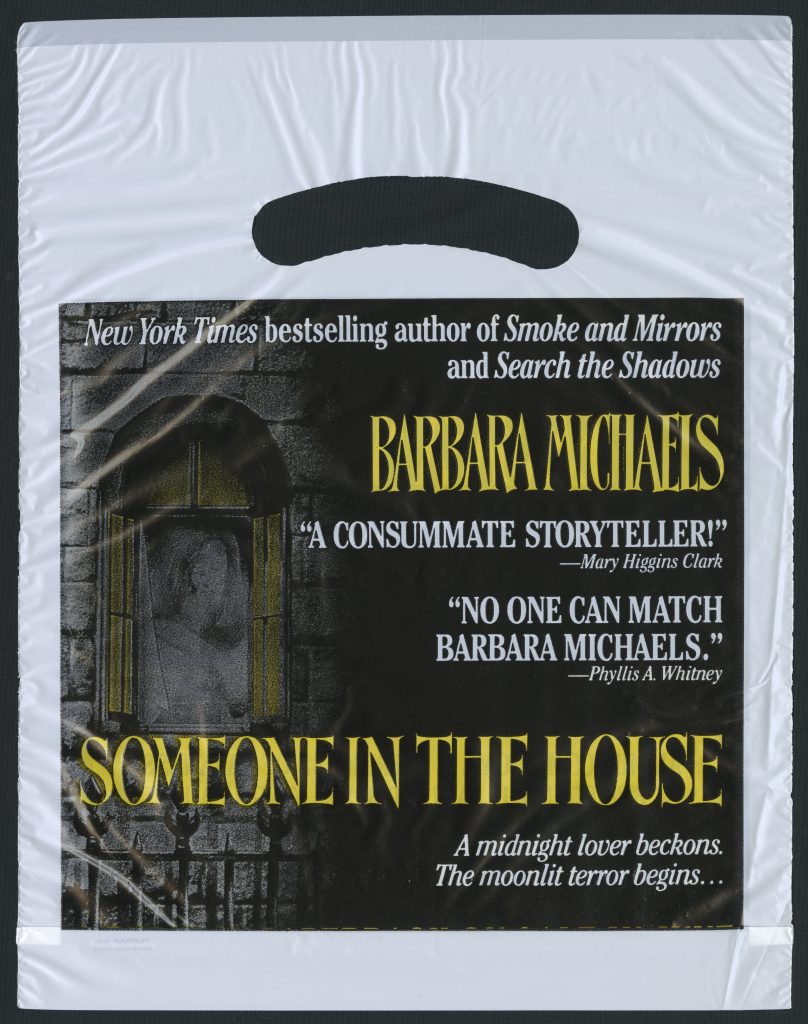

Another of my favorite parts of these series was the promotional ephemera for many of the books. From Borders-branded standees to plastic bags emblazoned with her book covers, I was impressed at how many different mediums Mertz’s publishers used to advertise and drum up excitement for her books. The sheer volume of promotional material illustrated just how popular and in demand her works were (and continue to be).

Continued with Journey to the Center of the Mertz Part 2.

3 Comments

Her library was acquired by O’Gara and Wilson Rare Books.

Dear Ava Dickerson,

Thank you for your Barbara Mertz archive update.

During a long illness I lost track of where parts of Barbara’s massive work and collections were sent. May I ask if you have knowledge of what happened to her extensive Library of books, and is it known that one of her umbrellas is a sword umbrella? What a joy it must be to dig into the treasure’s of Barbara’s personal and professional life.

Sincerely, Professor George B. Johnson

Thank you for this blog entry! I am a MPM fan and am so happy to see her collection in good hands. I’m also a librarian/archivist and loved reading about your work on this collection.